Whose America is it? Why I want my students to read Ta-Nehisi Coates but believe Lin-Manuel Miranda

By Robert Pondiscio

By Robert Pondiscio

I have no idea if Lin-Manuel Miranda has read Ta-Nehisi Coates’s Between the World and Me; nor am I aware if Coates has seen Miranda’s Hamilton on Broadway. But it would be fascinating to listen to the two of them discuss each other’s work and their views on what it means to be young, brown, and American today.

All of us who work in classrooms with children of color would be richer if we could eavesdrop on such an exchange.

The parallels are striking. Both are young men of color who have created two of the most praised and dissected cultural works of the moment. Both were recent and richly deserving Macarthur Foundation “Genius Grant” recipients. Each turns his creative lens on our nation. But their respective visions of America, signaled through their work, could scarcely be more different.

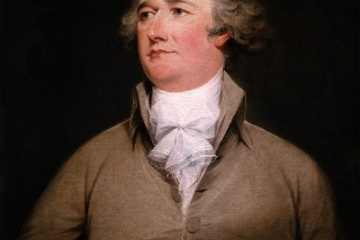

We can be a bit promiscuous in our use of the word “genius,” but if it applies to anyone, it’s Lin-Manuel Miranda. Anyone who can read, as he did, Ron Chernow’s seven-hundred-page doorstop biography of Alexander Hamilton and think “Hip hop musical!” has a mind like few others.

But where Miranda’s genius burns bright, Coates’s burns hot. He is, by a considerable margin, our most influential contemporary thinker on race. He has made that ongoing conversation both more potent and pointed, arguing for reparations to compensate African Americans for the effects of slavery and Jim Crow. Miranda’s vision is capacious and generous; Coates’s is focused and prosecutorial.

It is not an overstatement to say that Hamilton is a watershed moment in America’s cultural evolution and in the first rank of plays produced in our history. In less expert hands, a musical with rapping versions of Hamilton, Jefferson, and Washington would be “Springtime for Hitler” wince-worthy. But Miranda connects dots that no one else saw, drawing a straight line from America’s revolutionary moment to the contemporary music and idioms of youthful rebellion. The effect is mesmerizing.

It is impossible to think of our founders merely as dead white males once you have seen them embodied by young black and brown ones. On stage nightly, Hamilton transfers ownership of America’s narrative and ideals to those whose grip on them has been fraught for more than two hundred years. And Miranda’s genius runs in both directions. Your parents and grandparents don’t like rap? They haven’t seen Hamilton.

There’s likely not a history or civics teacher in America who wouldn’t pay dearly to have her students see Hamilton. It’s harder, however, to account for education’s romance with Coates, whose book Between the World and Me won the National Book Award and is already widely assigned in high school English classes and required reading on college campuses.

The book, an extended letter to his son, is a powerful jeremiad; but his message seems hopeless, even nihilistic. Coates’s America is structurally and irredeemably racist, and our schools offer no sanctuary. “I came to see the streets and the schools as arms of the same beast,” he writes. “One enjoyed the official power of the state while the other enjoyed its implicit sanction. But fear and violence were the weaponry of both.”

It is possible to read that as a teacher and think your personal commitment to social justice exempts you from this withering indictment. Coates does not just reject this notion; he sneers at it.

It does not matter that the “intentions” of individual educators were noble. Forget about intentions. What any institution, or its agents, “intend” for you is secondary. No one directly proclaimed that schools were designed to sanctify failure and destruction. But a great number of educators spoke of “personal responsibility” in a country authored and sustained by a criminal irresponsibility. The point of this language of “intention” and “personal responsibility” is broad exoneration. Mistakes were made. Bodies were broken. People were enslaved. We meant well. We tried our best. “Good intention” is a hall pass through history, a sleeping pill that ensures the Dream.

“The Dream”—the American Dream—is where Miranda and Coates part company. One says to young people of color that it belongs to them; the other says that it’s a lie. Perhaps Coates would tell Miranda that his view of Hamilton as immigrant American everyman (“Hey yo, I’m just like my country/I’m young, scrappy, and hungry”) sheds no light on the black experience.

Perhaps, he might insist, immigrants are allowed to rise in America because they don't carry the weight of history on their shoulders the way African Americans do. Would Miranda, the son of immigrants, agree? Coates might criticize Hamilton for soft-pedaling slavery and holding a gauzy view of history; Miranda would likely point out that the subject of slavery comes up in the third line of the show.

Near the end of Hamilton, Miranda, in the title role, sings,

I wrote some notes at the beginning of a song someone will sing for me.

America, you great unfinished symphony, you sent for me.

You let me make a difference.

A place where even orphan immigrants

Can leave their fingerprints and rise up.

Hamilton’s unfinished symphony invokes the constitutional call to build a more perfect union. The belief in this possibility, and the effort to bring it about, is why many of us teach—particularly those of us who work exclusively with children of color. Thus, it stings to read Coates saying, in effect, “Don’t waste your time.”

Wittingly or not, his message to young people of color is that they have had the great misfortune to be born in a country that is determined only to break their black bodies.

Coates’s America is “Egypt without the possibility of the Exodus,” in David Brooks’ memorable phrase. “African American men are caught in a crushing logic, determined by the past, from which there is no escape.”

For teachers, to see America through the eyes of Ta-Nehisi Coates is to see ourselves as either the oppressor or the oppressor’s tool. No other outcome is acknowledged or offered.

For the moment, Miranda seems to have the upper hand in this argument. Hamilton is the toast of Broadway. Its praises are sung by AP U.S. History teachers, its lyrics sung from the backseats of minivans. Coates may have the last word with our students, though.

Works of genius endure. Ten or fifty years hence, Coates’s memoir will arrive in English class unchanged. By that time, Hamilton will be among the most performed high school musicals in America. Lin-Manuel Miranda’s music and lyrics will remain; but performed by a white cast of teenagers in an American suburban high school, as it inevitably will be, Hamilton will sacrifice a bit of the moment and the cultural context that makes it great.

It will be a challenge for Miranda to ensure that the enduring message of Hamilton survives when most of our children’s exposure to his transcendent show will be not on Broadway or iTunes, but onstage in high schools. Coates’s message will remain potent, persuasive, and uncut. Perhaps this makes him the greater genius. He works in a medium that only time can dilute. The best we can hope for is that he proves to be a poor prophet.

It is simply not my place to disagree with Coates. I have not lived a day outside of “the Dream” he derides. In the wake of Eric Garner, Tamir Rice, and too many others to catalogue, I have no choice but to accept that he has come honestly by his dim view of America.

But as a teacher, I do not have the luxury of withholding hope from our students on behalf of the United States—a country whose optimistic citizens built our schools and pay our salaries, but one that still has much to answer for. For now, at least we can say this: A diverse nation that produces a Ta-Nehisi Coates and a Lin-Manuel Miranda is one in which something is going very right.

For all the differences between these two geniuses, both Coates and Miranda deserve to be heard, pondered, and debated equally. I will hang my hope here: I want my students to read Between the World and Me. But I want them to believe Hamilton.

Editor's note: This post originally appeared in a slightly different form at the Seventy Four.

This piece was first published on the education blog of The 74 Million.

William Phillis, the director of a lobbying group for Ohio’s school systems, recently stated in his daily email blast: “Our public school district is operated in accordance with federal, state and local regulations by citizens elected by the community....Traditional public schools epitomize the way democracy should work.” The email then went on to criticize charters for having self-appointed governing boards.

Setting aside charter boards for a moment, let’s consider the statement: Traditional public schools epitomize the way democracy should work. To quote tennis legend John McEnroe, “You can’t be serious.”

As observers of American politics would quickly point out, elections at any level of government aren’t perfect. One common concern in representative democracy is electoral participation. Approximately 40–50 percent of the electorate actually votes in midterm congressional races, and roughly 60 percent vote in presidential elections.

With only half of adults voting in some of these races, many have expressed concerns about the vibrancy of American citizenship.

But in comparison to school board races, national elections are veritable models of participatory democracy. In the fall of 2013, I calculated turnout rates in Franklin County school board races: Most turned out a measly percentage of registered voters — often less than 20 percent. (These rates would have skewed even lower had the entire voting-age population been used instead of registered voters.) Interestingly, during that cycle, Columbus citizens were not only electing school board members, but also deciding on a massive tax hike. And yet still, even with these seemingly critical matters on the ballot, only 19 percent of the electorate bothered to vote. Our friends at KidsOhio.org have noted the ongoing dismal turnout in Columbus, reporting in a policy brief that just 6 percent of adults voted in the spring 2015 school board primaries.

Paul Beck, a political science professor at Ohio State University, explained such low turnout rates, telling the Columbus Dispatch, “Voters are not really motivated to vote in these low-visibility contests.” Weak motivation is almost certainly a spot-on assessment. But further dampening public participation is the fact that in Ohio, school board elections are held “off cycle” — in non-congressional election years — when average voters aren’t paying attention to elections. Without the draw of high-profile candidates on the ballot, only the most attuned voters (or the most self-interested ones) participate in local school races.

Why don’t our champions of democracy, including the likes of Mr. Phillis, rush in to decry the woeful participation in school board elections? At the very least, why aren’t they clamoring to move school elections on cycle to ensure that more citizens’ voices are heard? The answer boils down to stone-cold self-interest.

You see, low-turnout elections protect interest groups deeply entrenched in the public education system. Research by Stanford’s Terry Moe demonstrates that low turnout provides an opening for special interest groups — most prominently labor unions — to capture school boards. When studying California board races, Moe observes that district employees — those with an occupational self-interest in the elections — tend to vote at higher rates than average citizens. Depending on the district, school employees were 2 to 7 times more likely to vote than the ordinary citizen. Unsurprisingly, voting rates were especially high when district employees both lived and worked in the same district. In conclusion, he writes, “Low turnout gives the unions an opportunity to mobilize support and tip the scale toward candidates they favor.”

Capturing school boards is an important goal for unions, as they will ultimately negotiate a labor agreement with the board. Given a union-friendly board, unions should be able to win managerial concessions during collective bargaining. These could include higher salaries and favorable benefits, or job protections such as rules around employee transfers, reductions-in-force, dismissal, class sizes, and grievance procedures. The various rules specified in these labor agreements (sometimes running hundreds of pages) stifle school leaders who aspire to organize their schools differently — and potentially in ways that better serve the interests of students, parents, and taxpayers.

Advocates of elected boards may claim that self-appointed charter boards are much worse. They’ll say that non-elected boards could have an overly cozy relationship with school management. To be sure, that’s a legitimate issue, and it shouldn’t be tolerated. Recently enacted House Bill 2 in Ohio weakens conflicts of interest like this (for more, see here). It is worth pointing out, however, that some of our most highly respected civic institutions have non-elected boards: One could easily name any number of responsible organizations that have excelled without elected boards (the Cleveland Clinic, the Columbus Museum of Art, and the United Way to name just a few).

Whether a school has an elected or self-appointed board isn’t the decisive factor in organizational success. A few districts may indeed thrive on public engagement via popular elections. But low participation, local politics, and the union influence shipwreck many more elected school boards. At the same time, some charter schools have smart, hard-working boards (though others do not). When it comes to school boards, what matters most is the character of those who serve — not how they were selected.

Opinions differed on the passage of the Every Student Succeeds Act, as they do with just about any piece of important legislation. But one thing that all sides agreed on was that the bill clearly signified a shift of control away from the federal government and toward the states. Some commentators celebrated the move away from distant, centralized power, while others fretted about the consequences for accountability—but the gist was pretty much the same. Now that we’ve entered the implementation phase, however, some are calling for a takeback. A coalition of over fifty civil rights organizations has signed a letter to Acting Secretary of Education John King urging his department to provide clear direction to the states for carrying out the law. The group—which includes the ACLU, the NAACP, the Human Rights Campaign, and Teach For America—recommends strong steps to guarantee equitable educational opportunities for English language learners, foster children, disabled students, and other disadvantaged populations. Whether they prevail will probably hinge on the amount of federal oversight states (and Republicans on Capitol Hill) are willing to tolerate after fifteen years of the No Child Left Behind precedent. History suggests that it won’t be much.

That’s not the only open letter Acting Secretary King will have on his mind this week. While the Senate education committee met today to approve his nomination for education secretary, members have received a written plea from liberal activists to torpedo his candidacy. The letter was reportedly drafted by author Nikhil Goyal (a person who is twenty years old), though “with the help of” eager chaperone and Common Core foe Carol Burris; signatories include waning campus eccentric Noam Chomsky and luminaries like the Badass Teachers Association. The text reproduces most of the brochure boilerplate associated with the opt-out movement, pillorying King for being a tool of nasty-wasty testing corporations. After the committee heeds their warning and votes King down, they’ll be free to formally eliminate homework and establish the Department of Joyful Illiteracy.

Years of experience have taught us that it’s not enough to just get kids to college; we’ve got to push them through as well. That’s because there’s no worse scenario than being saddled with loans intended to pay for a degree that was never fully attained. But educators in California are now arguing that we should look at things differently. A recent study of the state’s community college system, which closely tracked students who left without any kind of credential, seems to indicate that not all non-completers should be viewed as evidence of institutional failure. Researchers claim that many students intentionally attend just one or two CTE-centric courses, mostly in disciplines like IT and child development, as a means of acquiring professional aptitude and winning promotions. They dub these folks “skills builders,” and even though there’s something a little fishy about slapping a euphemistic name on the category (“He’s not an arsonist, he’s a bonfire enthusiast!”), the data paint a happy picture. According to information from California’s Employment Development Department, skills builders ended up earning a median wage bump of 13.6 percent—or nearly $5,000—after completing at least one CTE course. That’s impressive, and certainly something to think about as states consider holding colleges (and high schools) accountable for college completion.

Ah, to be seventeen again. What wouldn’t you give to roam the halls of your high school as a callow, idealistic youth? You could hang in with the JV cross country team, take a shot at your long-ago homeroom crush, and loudly tell off the class bully. And by God, you could take the watered-down SAT that today’s lucky kids are given, at last earning the perfect score you’ve always deserved! The ritually loathed test, bane of generations of slacker twerps, was subject to some radical changes this year: The vocabulary section was swept aside, the essay portion made optional, and the math problems updated to better reflect college-level expectations. According to Kaplan’s poll of students who’d recently sat for the exam, 72 percent said that it either “somewhat” or “very much” reflected the material they’d learned in class, while 70 percent said that it was either as difficult as they’d expected or somewhat less so. And no wonder! They’re no longer responsible for knowing the definition of the word “mollycoddled.”

In this week’s podcast, Robert Pondiscio and Alyssa Schwenk contrast the views of two MacArthur “geniuses,” weigh the role of “life experiences” in the college admissions process, and question reform critics’ push to block John King’s confirmation as education secretary. In the Research Minute, Amber Northern explains how DCPS gathers various data on teacher hiring but doesn't make the best use of them.

Brian Jacob, Jonah E. Rockoff, Eric S. Taylor, Benjamin Lindy, and Rachel Rosen, "Teacher Applicant Hiring and Teacher Performance: Evidence from DC Public Schools," NBER (March 2016).

Following hard on the heels of Fordham’s own report, Evaluating the Content and Quality of Next Generation Assessments, the Center for American Progress looks at the exams offered by the PARCC and Smarter Balanced (SBAC) testing consortia and largely likes what it sees for students with special challenges.

It’s a larger population than many perhaps realize. English language learners (4.4 million) and students with disabilities (6.4 million) constitute more than 20 percent of American school enrollment. “Given these numbers, it is critical that students with disabilities and English language learners have the same opportunities as their peers to demonstrate their knowledge and skills and receive appropriate supports to meet their needs,” the report notes.

Testing “accommodations” have typically meant extra time, questions read out loud or translated into native languages, and so on. While PARCC and SBAC “improve on previous state tests in terms of quality, rigor, and alignment” (Fordham’s report reached the same overarching conclusion) they also represent a significant advance in “universal design”—a principle that considers the user with the greatest physical and cognitive need and makes it a “feature,” not a “fix.” Consider the authors’ example of sidewalk “curb cuts.” Designed to make sidewalks wheelchair accessible, they ended up used by far greater numbers of non-disabled people, such as cyclists and mothers pushing strollers. That’s clear enough (and clever), but universal design principles are less obvious for tests. They include simple, clear, and intuitive instructions; precisely defined test items and tasks; and “accessible, nonbiased items” that are “sensitive to disability and students’ various cultural experiences.” “When assessment designers have the expectation that tests should be taken by all students, they create exams with every student in mind,” the report notes. Among the “features, not fixes” lauded by CAP for either PARCC, SBAC, or both: an item-specific, grade-appropriate glossary; translated test directions in nineteen languages; and digital notepads, calculators, and highlighters. The list of embedded accommodations is long, but the benefit of these design features is simple. It means that “students with disabilities and English language learners are less likely to take exams in a separate room or require the support of an aide, reducing the stigma around accommodations.” It also means that the tests are more likely to measure mastery of content and skills—not the ability to access the test itself. (For a comparison of the accommodations features for PARCC and SBAC, see page 44 of this HumRRO report.)

The PARCC and SBAC tests are a “major step forward for all learners,” the authors note, but they are not perfect. The majority of the forty-two current Common Core states were initially poised to administer one or the other; but, as the authors drily note, the two testing consortia have “paid a price during legislative battles.” Thus, states that have adopted one or the other “should continue to implement PARCC and Smarter Balanced assessments for their quality, rigor, and benefits for students with disabilities and English language learners.” But states that have fallen out of the consortia should take advantage of PARCC’s “flexible approach that allows states to use specific PARCC content when building their own tests.” SBAC materials are similarly available with approval by the consortium’s governing members. Using items á la carte would mean more “high-quality, universally designed items” in states’ homegrown assessments, the report concludes. A fine idea.

SOURCE: Samantha Batel and Scott Sargrad, “Better Tests, Fewer Barriers: Advances in Accessibility through PARCC and Smarter Balanced,” Center for Education Progress (February 2016).

Recently, the Council of Chief State School Officers (CCSSO) released a list of recommendations for states and local education agencies to use as a guide for designing and reforming teacher support and evaluation systems. The recently passed ESSA removes the federal waiver requirement for teacher evaluations, but most states have remained committed. And CCSSO’s guiding principles offer a solid foundation on which state and local authorities can refine their evaluation structures and teacher support systems to ensure a “productive balance” between support and accountability.

CCSSO worked alongside teachers, principals, state chiefs, expert researchers, and partner organizations to develop three key principles. The first highlights the importance of integrating teacher support and evaluation into more comprehensive efforts to develop teaching practice and improve student learning. This includes regularly communicating the purpose of evaluation and support systems; building systems that are based on clearly articulated standards for effective practice; connecting evaluation and support to talent management and using results to inform decisions related to career advancement, leadership opportunities, and tenure; aligning teacher support and evaluation to student standards, curricula, and assessment; and clarifying the roles and responsibilities of states, districts, and schools. States play the largest role in making the system work because, according to CCSSO, they are responsible for establishing underlying standards, vetting tools and resources to support local implementation, and collecting and analyzing meaningful data.

The second principle emphasizes the need for continuous improvement of teaching practice—not just integrating support initially, but doing so on a regular, consistent basis. To ensure continuous improvement, CCSSO recommends that teachers consistently receive frequent, action-oriented feedback directly connected to professional learning resources, as well as the chance to demonstrate growth over time based on feedback. States and districts can aid growth by creating structures for teachers to work in collaborative teams with peers and leaders—and by reallocating time and staff to create more effective professional development. Support should be differentiated and tailored based on what individual teachers need in order to best serve their students. School leaders must also be given the chance to build their skills through training and resources, with the end goal being constructive feedback to teachers.

The third and final principle is to ensure that the system is fair, credible, and transparent. To accomplish this, educators must be involved in the development and continuous improvement of the system. CCSSO advises that systems utilize multiple high-quality and reliable measures, including evidence of student learning and observation of teaching practice. These measures, however, must be balanced with professional judgment when assigning teachers summative ratings. States must also regularly examine data quality, system design, implementation, and other types of information—such as attendance, graduation rates, and disciplinary data—to ensure that results correlate with other important outcomes.

Overall, this is a solid list of recommendations for making teacher evaluation and support systems meaningful for all stakeholders. States looking to revise their evaluation policies would be wise to pay attention.

SOURCE: “Principles for Teacher Support and Evaluation Systems,” Council of Chief State School Officers (March 2016).

A new report by the National Charter School Resource Center examines the unique position of rural charter schools across America.

Citing a lack of research on the subject, as well as the demand for more examples of successful practice, the authors identify some of the unique difficulties that rural charter schools face: attracting and holding onto diverse local talent, paying to transport students over large distances, and maintaining and securing school facilities.

These challenges are often more acute for rural charter schools than their urban counterparts. There are hidden costs to teachers living and working in rural areas, such as a lack of suitable housing, professional growth opportunities, and good transportation. Providing transportation to students in areas with few alternative options may be prohibitively expensive. Simply locating appropriate buildings in which to operate a charter school is usually easier in an urban environment, where disused structures are more frequently available. When rural charters need to construct their own, costs rise exponentially.

Using examples in five states, the authors showcase a handful of rural charters that have overcome this adversity by using their position to their advantage.

The five case studies effectively demonstrate a variety of locally based solutions to rural charters’ struggles to cut costs, increase their community buy-in, provide better teacher support, and access high-quality curricular resources. It proves that these schools can thrive when rural policy makers and legislators give them the flexibility to innovate.

SOURCE: Mukta Pandit and Ibtissam Ezzeddine, “Harvesting Success: Charter Schools in Rural America,” National Charter School Resource Center (February, 2016).