The 2016 Brown Center report on education: How well are American students learning?

How tracking can raise the test scores of high-ability minority students

The teacher hazing ritual

Army brats for Common Core

The Lovitz edition

The 2016 Brown Center report on education: How well are American students learning?

The long-term effects of disruptive peers

How tracking can raise the test scores of high-ability minority students

ESSA accountability: Don't forget the high-achievers

Way back in the early days of the accountability movement, Jeb Bush’s Florida developed an innovative approach to evaluating school quality. First, the state looked at individual student progress over time—making it one of the first to do so. Then it put special emphasis on the gains (or lack thereof) of the lowest-performing kids in the state.

Many of us were fans of this approach, including the focus on low-achievers. It was an elegant way to highlight the performance of the children who were most at risk of being “left behind,” without resorting to an explicitly race-based approach like No Child Left Behind’s. [[they were virtually concurrent; I think it’s OK]]

Chad Aldeman of Bellwether Education Partners recently interviewed one of the designers of the Florida system, Christy Hovanetz, who elaborates:

By focusing on the lowest-performing students, we want to create a system that truly focuses on students who need the most help and is equitable across all schools. We strongly support the focus on the lowest-performing students, no matter what group they come from.

That does a number of things. It reduces the number of components…within the accountability system and places the focus on students who truly need the most help….It also reduces the need for small n-sizes. If you’re looking at the lowest-performing students in any given school, it’s a larger n-size than a lot of the race or curricular subgroups.

I still understand the impulse, but I’ve come to see this approach as a big mistake. That’s because it signals to schools that their low-achievers should be a higher priority than their high-achievers. And in a high-poverty school especially—where everybody is poor—that has the unintended consequence of hurting high-achieving, low-income students.

As I write in my new book, Education for Upward Mobility, these strivers deserve to be top priorities too. They are the low-income students with the best shot at using a great education to reach the middle class; to succeed in advanced courses in middle school and the AP program in high school; and to make it to and through four-year universities, including elite ones.

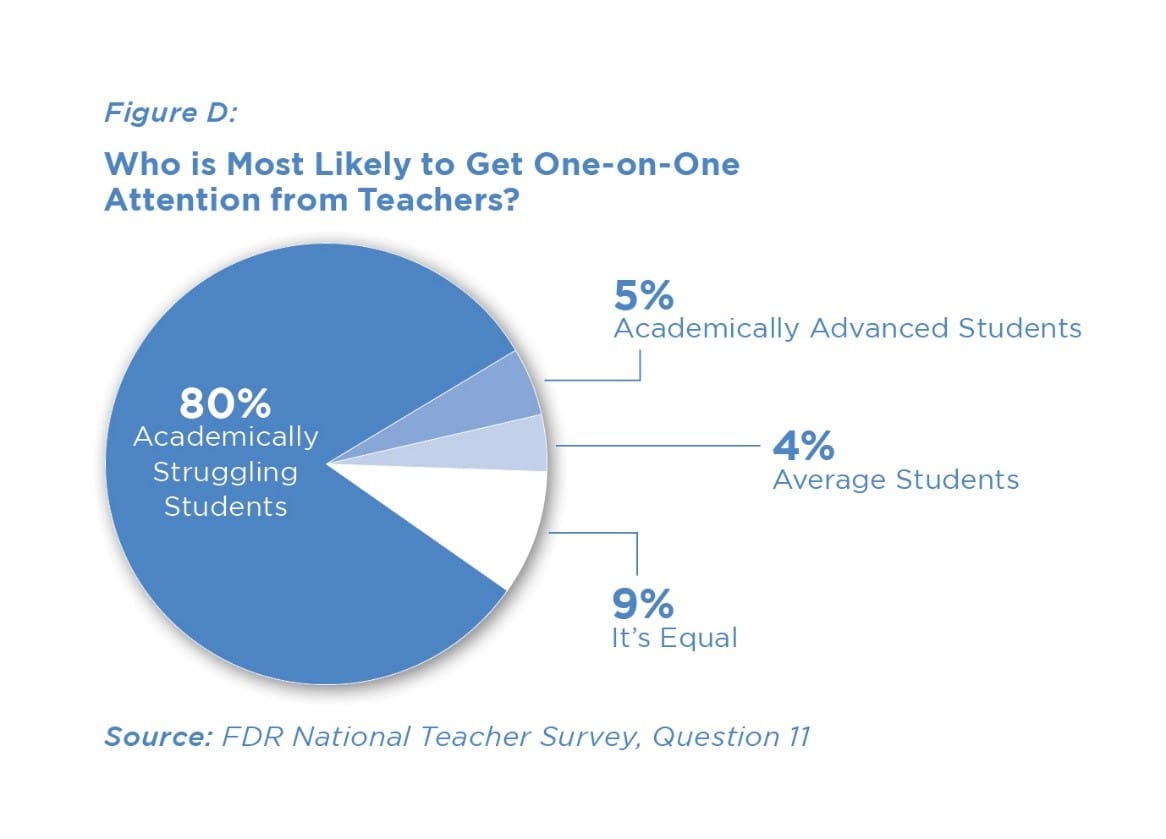

Yet too often their needs are an afterthought. In 2008, we at Fordham asked teachers whether they prioritized the low-achievers or high-achievers in their classrooms. It wasn’t even close.

That was back when NCLB was placing pressure on schools to get low-performing students over a modest “proficiency” bar—even while tacitly encouraging them to ignore the educational needs of their high-achievers, who were likely to pass state tests regardless of what their schools did for them. This may be why the U.S. has seen significant achievement growth for its lowest-performing students over the last twenty years (especially in fourth and eighth grades, and particularly in math), but minimal gains for its top students.

Thankfully, under the Every Student Succeeds Act, states now have the opportunity—and face the challenge—of designing school rating systems that can vastly improve upon the model required by NCLB. And one of the most important improvements they can make is to ensure that their accountability systems encourage schools to pay attention to all students, including their strivers.

In my view, state rating systems need to contain four crucial elements—all allowable under ESSA—if their high-achievers are again to matter to their schools:

- For the first academic indicator required by ESSA (“academic achievement”), give schools extra credit for achievement at the “advanced” level. Under ESSA, states will continue to measure the performance of students who attain proficiency on state tests. They should also give schools extra credit for getting students to the advanced level (such as level four on Smarter Balanced or level five on PARCC).

- For the second academic indicator expected by ESSA (student growth), grade schools using a true growth model that looks at the progress of students at all achievement levels, not just those who are low-performing or below the “proficient” line. Florida is not alone. Regrettably, many states still don’t consider student growth; alternatively, they may use a “growth to proficiency” system, which continues to encourage schools to ignore the needs of students above (or far above) the proficient level. Using a “value-added” or “growth percentile” method for all students is much preferred.

- When determining summative school grades, or ratings, make growth—across the achievement spectrum—count the most. ESSA expects states to combine multiple factors into school grades, probably through an index. Each of the three academic indicators (achievement, growth, and progress toward English proficiency) must carry “substantial” weight. But in my view, states should (and under ESSA, they are free to) make growth matter the most. Otherwise, schools will continue to face an incentive to ignore their high-performers.

- Include “gifted students” (or “high achieving students”) as a subgroup in the state’s accountability system, and report results for them separately. Finally, states can signal that high-achievers matter by making them a visible, trackable “subgroup,” akin to special education students or English language learners, and publishing school grades for their progress and/or achievement. (Obviously, it makes little sense to report that high achievers are…high achieving. But whether they are making strong growth is quite relevant. Alternatively, states might publish results for students labeled as “gifted,” though that opens up a can of worms about how those labels are applied.) To my knowledge, Ohio is the only state that currently does this.

What states should certainly not do is focus on the progress of just one group of students. All kids—and particularly all kids from disadvantaged backgrounds—deserve the best we can give them. Let’s not tell their schools otherwise.

The teacher hazing ritual

We are all familiar with the "hero teacher" narrative from books and movies: A plucky young (inevitably white) teacher ends up in a tough inner-city classroom filled with "those kids"—the ones that school and society have written off as unteachable—and succeeds against all odds, through grit and compassion, embarrassing in the process those who run "the system." Ed Boland's The Battle for Room 314 is the dark opposite. It's a clear-eyed chronicle of first-year teaching failure at a difficult New York City high school, vividly written and wincingly frank.

Reading the book brought back a flood of memories of my own struggles as a new teacher at a low-performing public school in the South Bronx. Like Boland, I had my share of defiant and difficult students. If I'd been teaching high school, not elementary school, I likely would have made the same decision he did: to abandon ship and return to my previous career after one year, shell-shocked and defeated.

Two things saved me. First, midway through my first year, another fifth-grade teacher was called up from the army reserve to active duty. I asked my principal to reassign me from my two-teacher "inclusion" classroom to take over her class. My other breakthrough was the discovery of The Essential 55, a book by Ron Clark built around a list of classroom rules he developed to teach his students to be attentive, engaged, and respectful. Taking over a new class gave me a fresh start in my first year and an opportunity to undo my rookie mistakes; Clark's fifty-five rules helped me develop a hard-nosed action plan to address my prodigious classroom management struggles. (It's worth noting that Clark's book was a direct repudiation of the training I'd received, which encouraged us to allow students to create their own classroom rules so they would feel "ownership" of their "classroom community." The only thing that got owned was me.)

With a fresh start and Clark's book as my new bible, the rest of my year went more smoothly. The next year was better still. I felt in control and able to teach. Boland never made it to year two. When his book came out last month, I was quoted in a New York Times piece about him, making what I thought was an obvious observation—that we simply assume it's normal for first-year teachers to struggle in the classroom. "Nobody says to an air traffic controller, ‘Everyone crashes a plane their first year; you'll get better,'" I told the paper. "It's not acceptable that that's part of the profession."

Almost immediately I received pointed emails from teachers. "Do you actually think that it is reasonable to expect any teacher, especially a new teacher, not to make mistakes on the job in a challenging inner-city school?" asked one.

Of course not. Veteran teachers make mistakes every day. My complaint is with the way we train teachers—or, more accurately, refuse to train them—in classroom management. The idea that every teacher struggles in his or her first year is not merely accepted but celebrated. And almost invariably, the teachers who struggle the most are in front of the students who can afford it the least.

Boland's book is more a memoir than a prescription for what ails teaching, and he is admirably candid about his own shortcomings as a teacher. But he makes abundantly clear that he was unprepared for the job he was asked to do. "Two years of graduate school and six months of student teaching offered me little to draw from. I had taken courses in lesson planning, evaluation, psychology, and research," he writes. "Next to nothing was said about what a first-year teacher most needs to know: how to control a classroom."

Note, too, that Boland was not a Teach For America corps member. Critics of such "alternative certification" programs (I was a New York City Teaching Fellow) often deride the preparation offered in these "teacher boot camp" programs. Boland went the traditional education school route, and it was a disaster.

"What little I had heard was wildly contradictory, a mix of folk wisdom, psycho-jargon, wishful thinking, animal training, and out-and-out bullshit," Boland writes. Most of what he learned wasn't even from his education school professors, "but from the shell-shocked first-year teachers I shared my classes with. The majority of our professors hadn't taught in a public school in ages, if ever.”

I know Boland personally; I worked for him briefly at an education nonprofit called Prep for Prep. He's exactly the kind of person sought out by those who think raising teacher quality is the answer to what ails American education. He's well-educated, quick-witted, engaging, and deeply committed to education—particularly for low-income children of color. It was hard not to read his memoir without concluding that he was failed by those who trained him, hired him, and left him to crash and burn.

"We treat first-year teaching like it is some sorority or fraternity hazing," notes Kate Walsh, the head of the National Council on Teacher Quality. "Educators expect a new teacher to be sick to her stomach at the thought of how she is going to survive the day, just because that's what they once did. It's appalling!"

She's right. It's difficult to pinpoint why we seem so averse to making classroom management the centerpiece of new teacher training. Just the word "training" seems anathema to education schools. Training is for cops, firemen, electricians, air traffic controllers. It's hard not to see a bit of intellectual or professional insecurity at work in education schools' reluctance to stress classroom management.

Teacher quality advocates tend to talk mostly about "accountability"—measuring teacher performance, rewarding high-fliers, and counseling out those with lackluster results. We focus too little attention on how poorly prepared too many instructors are for the hardest jobs in the field. We assume struggling schools are filled with untalented or tenured layabouts. Far more often, these teachers are good people trying their best and failing. And they fail not in spite of their training, but because of it.

Editor's note: This post originally appeared in a slightly different form at U.S. News & World Report.

Army brats for Common Core

- Even before they start school, inner-city students are often beset by huge learning obstacles—from the infamous thirty-million-word gap to the perils of urban violence—that need to mitigated by overtaxed districts. There’s a morbid irony, therefore, in new findings suggesting that these kids face the additional danger of poisoning once they walk into school. Nationwide testing in the wake of the Flint crisis has revealed distressing levels of lead contamination in school systems from Los Angeles to Newark. The problem has gone largely undetected for years because the only statute governing lead levels in public water supplies is a grossly inadequate 1991 EPA rule. Countless district facilities around the country are exempted from its language, and their lead-lined pipes and water coolers are spreading pollutants that are known to damage children’s bodily organs and stunt intellectual development. Disadvantaged families need to know that their kids are safe at school, not at risk of sustaining irreversible biological harm.

- We all know the hallmarks of a typical civics lesson: dust-dry soliloquys about the Virginia Plan versus the New Jersey Plan, yellowed daguerreotypes of Abraham Lincoln, and melodically flaccid episodes of Schoolhouse Rock. If there were any class period that could use some sprucing up from goodhearted techies, it’s probably this one. So we can be grateful for iCivics, an education nonprofit founded by former Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor. The group works with designers to develop civics-based video games like Win the White House, which challenges students to concoct their own presidential candidates and platforms. As she puts it, O’Connor was driven to start the organization by the disturbing numbers of “adults who don’t know anything about civics” (yes, Madam Justice, we know). There are loads of untapped potential in digital play, which holds an instinctive appeal for children and is versatile enough to impart skills and knowledge from a variety of disciplines. For more on the subject, check out Fordham’s 2015 discussion with author and game enthusiast Greg Toppo.

- One of the biggest knocks against common academic standards and assessments is delivered by state legislators, who claim that educational expectations in Indiana (or Massachusetts, or Utah) should be unique to the state itself. I don’t really credit the validity of that idea (last time I checked, algebra in the Rockies doesn’t differ from algebra on Cape Cod), but there’s another issue to consider: For students who move to new schools in different states, uniformity is actually a boon, ensuring that they aren’t rehashing familiar material or plunged into bewildering new coursework. It was probably inevitable, then, that a Common Core advocacy group would spring up among parents who serve in the armed forces. Since military families tend to relocate between six and nine times during their children’s K–12 years, our national patchwork of wildly disparate school quality can pose a unique challenge. With Common Core gradually becoming accepted in nearly every state, though, our soldiers, sailors, and airmen won’t have to worry so much when the rental van pulls into the driveway.

The Lovitz edition

On this week's podcast, Robert Pondiscio and Alyssa Schwenk discuss Sean "Diddy" Combs's new Harlem charter school, the fizzling out of the Friedrichs Supreme Court case, and America's lack of effective teacher training. During the Research Minute, Amber Northern reviews the 2016 Brown Center Report on American Education.

Amber's Research Minute

"The 2016 Brown Center Report: How Well Are American Students Learning?," Brown Center on Education Policy at Brookings (March 2016).

The 2016 Brown Center report on education: How well are American students learning?

If I had to pick just one reason to support Common Core, it would be to address the paucity of nonfiction texts read by students in elementary and middle school reading instruction. Gaps in background knowledge and vocabulary make it stubbornly difficult to raise reading achievement. Conceptualizing reading comprehension as a skill you can apply to any ol’ text broadly misses the point. By encouraging reading in history, science, and other disciplines across the curriculum, Common Core encourages “a foundation of knowledge in these fields that will also give [students] the background to be better readers in all content areas.”

Thus, it is great good news that the 2016 Brown Center Report on American Education finds the dominance of fiction waning in the fourth and eighth grades. The standards call for a 50/50 mix of fiction and non-fiction in fourth grade. In 2011, 63 percent of fourth-grade teachers reported emphasizing fiction in class, while only 38 percent said they emphasized non-fiction. A mere four years later, the gap is down to just eight percentage points (53 percent to 45 percent).

On the math side, CCSS asks for fewer topics or strands, as well as a focus on whole number arithmetic from kindergarten through fourth grade. “Teachers appear to be responding to the new focus,” writes report author Tom Loveless. “Fourth-grade teachers do not teach as much data and geometry as they once did,” he notes. “Neither domain received as much attention in 2015 as in 2011 or prior years.”

Let’s stop for a moment and not bury the lede: Two of the most important and valuable instructional shifts encouraged by Common Core are actually happening. In a field bedeviled by unintended consequences, this is something new under the sun. Changes in classroom practice encouraged from outside schools typically resemble a child’s game of telephone: A simple message can change dramatically with multiple retellings. If messages like “more nonfiction” and “fewer, deeper topics” in math are getting through to teachers intact, that’s not a bad thing and not a bad start.

To be sure, there’s far more we do not know about Common Core’s impact on instructional practice. Text selection is one of the most important decisions a school or district can make. The report sheds no light on the merits or complexity of texts put before children, or whether or not the amount of close reading demanded of students is growing or shrinking. The Brown Center study also finds “a dramatic change in the math courses taken by eighth graders.” Enrollment in advanced math courses (most notably algebra) has fallen from 48 percent to 43 percent, while enrollment in “general math” has seen a concomitant rise in enrollment from 26 percent to 32 percent—also attributable to Common Core adoption. Nothing, it should be noted, prevents states from insisting the every eighth grader take Algebra I—although the case has been made that too much advanced math, rather than increasing the number of college-ready students, has been increasing the number of high school dropouts instead.

The report explores whether middle school tracking is related to AP participation or test scores in high school, using state-level tracking data from 2009 and AP data from 2013. “[S]chools in communities serving large numbers of black and Hispanic students tend to shun tracking, while accelerated classes are less likely to exist for students of color,” notes Loveless, who nonetheless finds a positive relationship between tracking and superior performance on AP tests (scoring 3 or better) among white, black, and Hispanic students. He takes care to observe that the analysis “cannot prove or disprove that tracking caused the heightened success on AP tests.” However, he notes, “the findings do support future research on the hypothesis that tracking benefits high-achieving students—in particular, high-achieving students of color—by offering accelerated coursework that they would not otherwise get in untracked schools.”

Back to Common Core, the Brown Center report finds no relationship between strong, medium, and non-implementers of Common Core and changes in NAEP scores from 2009 to 2015. Gains and losses among all levels of implementation fall within a single NAEP scale score point. “Many advocates of CCSS have a theory of implementation that believes these standards are so new, so revolutionary, so different from what teachers have experienced previously that Common Core won’t bear fruit for many years,” Loveless explains.

Sort of. It’s a combination of instructional shifts, plus the weaknesses in K–12 revealed by the standards, that are likely to point to the richest vein of ore to mine. It’s also true that tests associated with the standards were only administered for the first time last year (the same year NAEP was in the field), and tests almost certainly have a greater effect on classroom practice than standards alone. This will take considerable time to bear fruit, but I’d be deeply suspicious of any rapid gains attributed to Common Core—on NAEP or elsewhere. You should be too.

SOURCE: Tom Loveless, “The 2016 Brown Center Report on American Education: How Well are American Students Learning?,” Brookings Institution (March 2016).

The long-term effects of disruptive peers

A new study examines the effects of disruptive elementary school peers on other students’ high school test scores, college attendance, degree attainment, and early adult earnings.

Analysts link administrative and public records data for children enrolled in grades 3–5 in one large Florida county (Alachua) between the years of 1995–1996 and 2002–2003. The demographic and test score data are linked to domestic violence, which is the part of the study that strikes me as odd.

They define “disruptive peer” not by how many times a child is disciplined in school or the severity of the offense, but rather by a proxy—whether a member of the child’s family petitioned the court for a temporary restraining order against another member of the family. Apparently, the literature shows that children exposed to domestic violence are more likely to display a number of behavioral problems, among them aggression, bullying, and animal cruelty. Another study showed these students negatively affected their peers’ behavior. Nevertheless, calling these students “disruptive peers” is a misleading characterization given the lack of documented school infractions. They are kids exposed to domestic violence, and the findings should be understood within this light.

That said, here are the results: Estimates show that exposure to one additional disruptive student in an elementary school class of twenty-five reduces math and reading test scores in grades nine and ten by .02 standard deviations. Moreover, exposure to male disruptive peers—or those subject to as-yet unreported domestic violence—results in larger negative effects on high school test scores and significant declines in college degree attainment. (They observed some students before a restraining order was filed; yet after one is filed, abuse tends to stop or decrease, so it makes sense that exposure to a peer with as-yet unreported violence would be “worse.”) Exposure to an additional disruptive peer throughout elementary school also leads to a 3–4 percent reduction in earnings from the ages of twenty-four and twenty-eight and reduces the likelihood of receiving any type of college degree by anywhere between 0.7 and 2.6 percentage points. Disruptive peers have the largest effects on the test scores of high-achievers. White students are estimated to experience a reduction of earnings of roughly 5 percent if exposed to one disruptive student, which is twice the estimated effect for black students.

How tracking can raise the test scores of high-ability minority students

This study examines the impact of achievement-based “tracking” in a large school district. The district in question required schools to create a separate class in fourth or fifth grade if they enrolled at least one gifted student (as identified by an IQ test). However, since most schools had only five or six gifted kids per grade, the bulk of the seats in these newly created classes were filled by the non-gifted students with the highest scores on the previous year’s standardized tests. This allowed the authors to estimate the effect of participating in a so-called Gifted and High Achieving (GHA) class using a “regression discontinuity” model.

Based on this approach, the authors arrive at two main findings: First, placement in a GHA class boosts the reading and math scores of high-achieving black and Hispanic students by roughly half of one standard deviation, but has no impact on white students. Second, creating a new GHA class has no impact on the achievement of other students at a school, including those who just miss the cutoff for admission. Importantly, the benefits of GHA admission seem to be driven by race as opposed to socioeconomic status. They are also slightly larger for minority boys than minority girls (especially in reading).

As the authors note, these differences between groups aren’t easily explained by factors like teacher quality, peer composition, and the “match” between student ability and the level of instruction—each of which might be expected to benefit all GHA students (or none). This interpretation is largely confirmed by a direct examination of these factors, which suggests that differences in teacher quality between GHA and non-GHA classes do not explain the achievement gains experienced by minority students in the former, and that differences in peer composition explain just 10 percent of these gains.

In light of these findings, the authors hypothesize that higher-ability minority students face obstacles in the regular classroom environment—such as lower teacher expectations and negative peer pressure—that cause them to underperform relative to their potential, and that some of these obstacles are reduced or eliminated in a GHA class. To support this hypothesis, they use data from an IQ-like test called the Nagliari Nonverbal Ability Test (NNAT) to show that minority students have lower achievement scores than white students with similar cognitive ability. For example, black students’ third-grade achievement scores are between 0.2 and 0.45 standard deviations below those of white students with similar NNAT scores, suggesting an “underachievement gap” similar in magnitude to the boost these students receive from a GHA classroom.

In a previous study conducted in the same school district, the authors also found that switching from a giftedness identification system based on teacher nominations to an automated process based on NNAT scores led to increases of 80 percent and 130 percent, respectively, in the numbers of black and Hispanic students identified as gifted, suggesting that teachers were either unaware of these students’ cognitive ability or unwilling to overlook their comparatively low achievement. Based on this finding, the authors argue that high-achieving minority students may benefit from GHA classes in part because teachers are more likely to recognize their potential in a GHA context.

Citing the ethnographic research on minority underperformance, the authors also suggest that the pressure to avoid "acting white" by achieving at a high level may be reduced for minority students in a GHA class, where all students are labeled as gifted or high-achieving. As evidence for this hypothesis, they cite lower rates of unexcused absences and suspensions among minority students in GHA classes.

Both of these explanations are plausible (if difficult to prove). But regardless of the true explanation, the fact that high-achieving minorities see such clear benefits from a policy of achievement-based “tracking” should give die-hard proponents of “equity” pause. After all, it’s one thing to prioritize those at the bottom, but it’s something else entirely to hold back those who could achieve escape velocity because they are short on company.

Perhaps it’s time we found a better word for encouraging these students to embrace their academic potential than “tracking.”

SOURCE: David Card and Laura Giuliano, "Can Tracking Raise the Test Scores of High-Ability Minority Students?," NBER (March 2016).