How principals' professional practices affect student achievement

Let's re-introduce competition into our classrooms

Getting better all the time

The DNC edition

How principals' professional practices affect student achievement

Homeless students in American schools

Stronger schools through community organizing

How to close the enrichment gap

Late July might be famous for potato chips and trips to the beach. But it’s also the time when America’s inequality, like the hot summer sun, is at its zenith, particularly for our children. Affluent kids are spending their days (and often their nights) at camp or traveling the world with their families, picking up knowledge, skills, and social connections that will help them thrive at school and beyond. Needless to say, these experiences are seldom accessible to their less affluent peers.

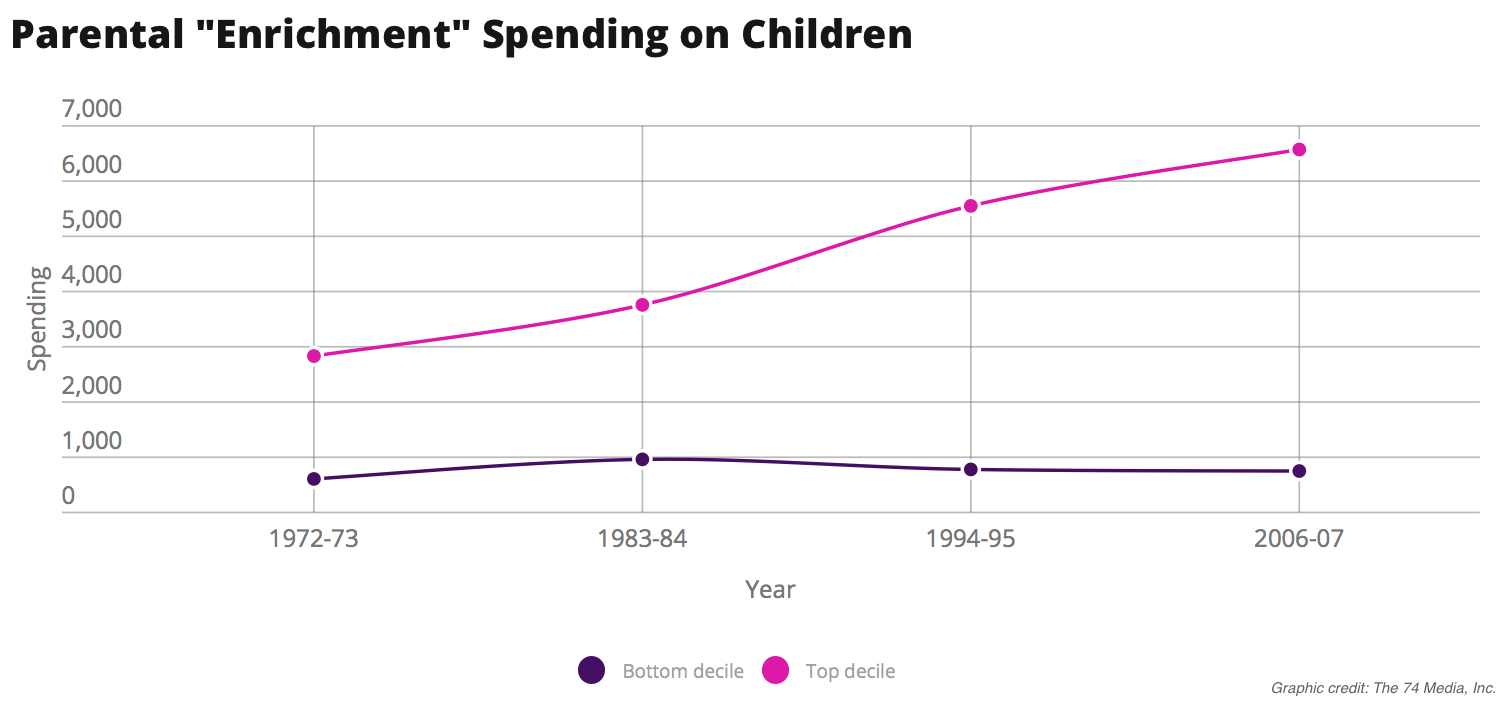

As Robert Putnam argued in his landmark book Our Kids—and again in his recent report, Closing the Opportunity Gap—there is a growing class gulf in spending on children’s enrichment and extracurricular activities (things like sports, summer camps, piano lessons, and trips to the zoo). As the upper-middle class grows larger and richer, it is spending extraordinary sums to enhance its kids’ experience and education; meanwhile, other children must make do with far less. (Putnam got the data for his chart from this study.)

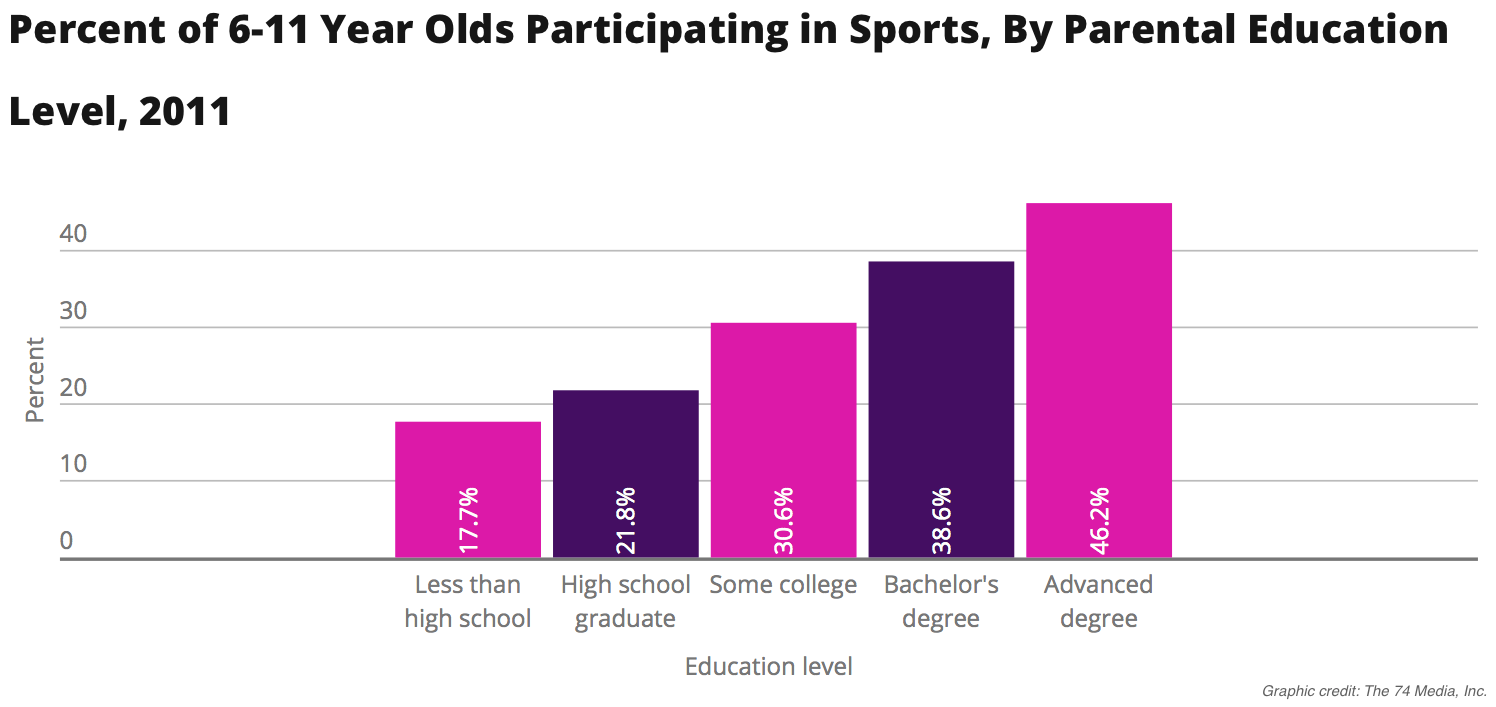

More critically, that gap shows up in participation rates too. The Census Bureau tracks involvement in out-of-school sports, clubs, and lessons (e.g., music, dance, Hebrew). Here’s what sports participation looks like for children ages 6–11 broken down by parental education level, a good proxy for social class:

As is evident, not every first grader plays soccer, even if that feels like the suburban norm. Children whose parents have advanced degrees are three times likelier to participate in sports than those whose parents dropped out of high school. The picture looks much the same for clubs and lessons, as well as for high school students’ involvement in extracurricular activities.

These are enormous differences. As Annette Lareau pointed out in Unequal Childhoods, affluent kids are scheduled to the hilt, while poor and working class kids’ spare time is largely self-organized. Though that kind of “free range” experience brings some benefits, it also means less intellectual stimulation, social development, and basic safety for the have-nots. Years later, the “overscheduled” kids seem better able to navigate college and the adult world. (Of course, they’ve also had other advantages.)

After school, over the weekend, and during summer are also great times for kids to work on their “identity projects”—a term coined by Stefanie DeLuca, Susan Clampet-Lundquist, and Kathryn Edin in their recent book, Coming of Age in the Other America, to refer to passions that propel children to long-term success. Such projects usually take the form of artistic, creative, vocational, and enrichment activities that give young people meaning and direction (and the option of not being on the street). As DeLuca told me in an email, these pursuits “sparked the grit to stay in school and avoid trouble, and select into better peer groups.”

A growing body of research attests to the positive impact of participation in extracurricular and enrichment activities. The evidence is particularly strong for high school athletics, where a handful of studies have been able to establish a causal link between participation and positive long-term outcomes. The most prominent is a brilliant analysis by Betsey Stevenson that examines the impact of Title IX on girls’ participation in high school sports, finding a significant increase in college going and labor force participation. A trove of correlational studies have also demonstrated benefits for high school athletes, including higher grades, increased graduation and college completion rates, and a decrease in various antisocial behaviors. There are similar results for students who participate in other extracurricular activities, such as clubs, especially if they play leadership roles or are deeply committed.

There is somewhat less evidence pointing to the benefits of enrichment activities for younger students; as far as I can tell, no one has established a causal link between enrichment and long-term outcomes. But there’s plenty of correlational as well as anecdotal evidence. Scholars have mostly looked at after-school programs. There, too, they find a correlation between participation and positive outcomes, at least when attendance is regular and there’s a strong connection to an adult role model.

What explains the connection between enrichment activities and student success? We cannot be certain, but mentors are surely part of it. So is the development of those “non-cognitive” and “social and emotional” skills that have everyone’s attention. Sure, you can try to teach “grit” in math class (though there are reasons to be skeptical), but isn’t football, dance, karate, or violin likely to be at least as valuable a venue?

***

Although extracurricular and enrichment opportunities are valuable for young people, the vast majority of low- and moderate-income children don’t have access to a full measure of them. How might we change that and make it likelier for poor kids to take part in high-quality enrichment along with their affluent peers?

If we could muster the public will to invest serious financial resources, an obvious option is simply to give their parents money. An expanded child tax credit, or more generous Earned Income Tax Credit, would put more cash in moms’ and dads’ pockets, some of which might find its way to after-school activities, soccer leagues, or summer camps.

Another approach is to beef up support for existing after-school and summer programs. The most specific federal investment is via the 21st Century Learning Centers program, which funds afternoon programs at high-poverty public schools and currently receives more than $1 billion per year. Grants from the Child Care and Development Fund (CCDF), which receives almost $3 billion in discretionary money annually, can also be targeted to such activities for children up to age twelve. States can also transfer a portion of their Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) funds into the CCDF and use it for after-school and summer programs. A variety of targeted programs housed at the Departments of Justice, Housing and Urban Development, and Agriculture can also be tapped for this purpose.

Another possibility—Putnam’s favorite—is getting rid of “pay-to-play” policies for high school sports and other extracurriculars. If participation in these activities has positive benefits for students, why would we erect financial barriers to them?

My own preference is to create “enrichment savings accounts.” Taking their inspiration from health and education savings accounts, the notion is to give parents the equivalent of a debit card to be used for sports, art, summer camps, Girl Scouts, and all the rest. Education savings accounts already allow for expenditures on these sorts of things, but they are limited to a few states and can also be used for private school tuition. The “savings” part is critical, since it encourages parents to be careful, prudential, discerning shoppers, getting the most bang for their buck while keeping costs down. Parents could roll over the savings from year to year and eventually use them for college.

If this is a good idea, there are significant design questions to think through. Should it be universally available or limited to low- and moderate-income families? What would be allowable under the “enrichment” umbrella? Could schools’ extracurricular activities be funded through these ESAs? (And would that perversely encourage even more public schools to charge kids to play sports?) How much money would be enough to make an impact?

The best approach, probably, is “all of the above.” The federal government might sponsor a competition for states that want to boost their extracurricular and enrichment participation rates for disadvantaged youth. Money could come from existing programs (including the CCDC and TANF); perhaps some new federal dollars could sweeten the pot. And then states should try out a variety of these ideas, evaluating them rigorously. We could find out whether any of them dramatically raises participation in a cost-effective way and manages to get positive short- and long-term results.

But that’s for another day. For now, imagine a world where the summer, weekend, and after-school experiences of the poor aren’t as radically different as they are today for the rich, and where every American child gets to enjoy the ups and downs of youth soccer, summer camp, and everything else. That is a world I’d like to live in.

Let's re-introduce competition into our classrooms

Every instructional strategy, from direct instruction to the flipped classroom, elicits both negative and positive outcomes depending on when, where, and how it is employed. When it comes to using competition, however, schools tend to favor cooperative learning as the preferred approach for inter-student activities designed to increase learning and motivation.

Negative views of competition stem from early research purporting that its use in most contexts led to undermined motivation, negative self-concept, and anxiety on the part of participants. However, research on resiliency highlights the fact that adverse conditions do not universally lead to despair; they may, in fact, fuel motivation for high levels of achievement. Failure to achieve valued goals (e.g., winning a competition) may hurt, but the result does not have to be debilitating. In fact, experiences with competition during youth present opportunities to fail under safe conditions. In doing so, they provide lessons on how to manage the range of emotions and possible behavioral responses to setbacks, particularly for those who have been sheltered from such experiences. Thus, participating in competitions also facilitates teaching about coping skills in the face of disappointment.

Another important benefit of competition is deriving feedback that leads to self-reflection and improvement. If losing a competition meant that participants would shun that activity, many world records and products would not exist. Moreover, embracing competition means that youth are taught to admire accomplishments and celebrate individual differences as a fundamental area of diversity.

Competition as an instructional strategy (such as in-class science fairs, spelling bees, or timed, complex team assignments) is clearly more stressful for some than others, and it also differs by context. For example, positive outcomes from competition are enhanced when conditions are explicitly fair (not pre-ordained) and when students are sufficiently competent in the subjects or skills that serve as the basis of a competition. We know that boys and girls respond differently to competition depending on perceptions of their peers’ abilities compared to their own. Both boys and girls can be coached on how to deal with ruminations about setbacks or failure across the academic domains, just as in performance domains such as dance, athletics, or music. They can also learn how to perceive the stress of competition as a challenge rather than a threat. By allowing youth an opportunity to experiment with competition and practice mental and social skills (with proper mentoring), we provide a foundation for approaching competition with confidence instead of trepidation, and help them learn to judge their worth on the basis of challenging the self rather than winning the prize.

Educational policy and practice suffers when we adopt extreme views, and until recently the fields of psychology and education left the negative view of competition as an instructional strategy virtually unchallenged. As a result, the potential benefits of competition have been diminished as a tool for school personnel (outside of extracurricular sport, performing arts, and contests such as Olympiads and science fairs). Teachers, parents, coaches, and supervisors need a broad array of tools to facilitate optimal performance, and they are hampered when some motivational strategies, such as constructive competition, are viewed as off limits. From school-based sports leagues to writing grants for research funding and the range of competitions on popular reality television shows, competition is ubiquitous in society. In today’s world, not preparing students to engage in constructive competition can be considered educational malpractice.

Scientific support for this op-ed will appear in an upcoming edition of the Review of General Psychology.

Frank C. Worrell is a professor in the Graduate School of Education at the University of California, Berkeley. Rena F. Subotnik is the director of the Center for Psychology in the Schools and Education at the American Psychological Association.

This article was also written in collaboration with the members of the American Psychological Association’s Coalition for Psychology of High Performance, which is funded by the American Psychological Foundation:

Frank C. Worrell, Ph.D., University of California, Berkeley

Steven E. Knotek, Ph.D., University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill

Jonathan A. Plucker, Ph.D., Johns Hopkins University

Steve Portenga, Ph.D., iPerfomance Psychology

Sheila R. Schultz, Ph.D., HumRRO

Dean Keith Simonton, Ph.D., University of California, Davis

Rena F. Subotnik, Ph.D., American Psychological Association

Megan Foley-Nicpon, Ph.D., University of Iowa

Jonathan Metzler, Ph.D., Armed Forces Services Corporation

Paula Olszewski-Kubilius Ph.D., Northwestern University

Getting better all the time

- Good news from out west: According to a new study conducted jointly by Stanford, the University of Washington, and the RAND Corporation, our newer cohorts of teachers are entering the profession with appreciably better academic pedigrees than their predecessors of fifteen and twenty-five years ago. The researchers measured the SAT and ACT scores of about three thousand recently hired teachers across the United States from 1993, 2000, and 2008. While the Y2K-era newbies scored only in the thirty-ninth percentile for average SAT/ACT math, the 2008 group soared all the way to the commanding heights of the forty-sixth percentile! (Hey, any improvement is welcome, even if the beginning of the Great Recession probably played a role in ushering more qualified candidates into the profession.) If the news doesn’t exactly have you rushing for your party hats, consider this: Contrary to popular belief, the era of greater teacher accountability following No Child Left Behind hasn’t dissuaded good young candidates from entering the classroom.

- You can do a lot to improve education for underprivileged kids—improve teacher quality, tighten up academic standards, institute cultures of accountability—and still not make much progress toward closing the achievement gap separating them from their more advantaged peers. That’s because so much of that gap opens up while children are out of school: either before they hit kindergarten (when comparatively affluent kids are benefiting from the millions more words being spoken around them) or in the summer (when they pack up for summer camp and educational trips). Thankfully, a new program in Montgomery County, Maryland, is aiming to narrow both the achievement and enrichment gaps. Intended to serve more than four thousand struggling second and third graders over four years, the initiative is a kind of hybrid summer school/summer camp. It cushions against the damage of the “summer slide” with intensive classroom study, but mixes in art projects and field trips that many of its charges wouldn’t otherwise be able to access. These types of activities, along with sports and music lessons, are often denied to working-class and low-income kids, and the county should be commended for trying to level the playing field.

- The Ford Foundation made huge waves last year with the announcement that it would be reorienting its mission—along with its half-billion-dollar budget—toward the global struggle against inequality in all of its forms. This week, in a lengthy open letter published in Philanthropy magazine, Bush administration veterans Michael Gerson and Pete Wehner have urged the organization to instead pledge its resources to the related issue of social mobility. Warning against the danger of “drawing households into low-level subsistence instead of equipping them to seek something better,” the authors recommend a reprioritization of the problems of family disintegration and crumbling civic institutions in economically distressed areas. These are scourges lamented by social scientists like Robert Putnam and Charles Murray, but Fordham President Mike Petrilli also wrote a whole book on it. If striving families are going to get a chance to claw their way into the middle class, we’ll have to fix public schools first.

The DNC edition

On this week’s podcast, Mike Petrilli, Robert Pondiscio, and Alyssa Schwenk discuss education policy at the Democratic National Convention, along with ways to close the enrichment gap. During the research minute, Amber Northern examines whether weighting Advanced Placement courses higher in student GPAs increases enrollment.

Amber's Research Minute

Kristin Klopfenstein and Kit Lively, "Do Grade Weights Promote More Advanced Course-Taking?," Association for Education Finance and Policy (Summer 2016).

How principals' professional practices affect student achievement

A new Mathematica study examines whether principal evaluations are accurate predictors of principal effectiveness as measured by student achievement. Researchers have done some research on the validity of teacher evaluation measures, but principal measures are less studied.

The authors examine a principal evaluation measure called the “Framework for Leadership” (FLL), which was developed by the Pennsylvania Department of Education as part of a mandated revision of the state’s principal evaluation process. Superintendents and other district supervisors use the tool to assess principals, and it includes twenty leadership practices grouped into four domains. These domains comprise practices that, when employed by principals, the state believes can raise student achievement. The four domains are strategic/cultural leadership, systems leadership, leadership for learning, and professional and community leadership (more on some of these later).

The study uses data from the pilot implementation of the FLL—which had no consequences for principals who participated—during the 2013–14 school year. The study focuses on 305 of the 517 principals in the pilot for whom the analysts had suitable administrative data. It included state test scores for all Pennsylvania students who were administered state math and reading tests from 2006–07 to 2013–14, in grades 3–8 and the eleventh grade. Also included were test scores from other grades and subjects where the data were available, such as science in grades four, eight, and eleven and writing in grades five, eight, and eleven.

To account for school-level factors outside of the current principal’s control (such as neighborhood safety or the effectiveness of teachers hired by previous principals), analysts compared the school’s value added before the arrival of the sampled principal with its current value added. Then they assessed the extent to which principals with higher value added earned higher FLL scores than principals with lower value added.

Key findings: The FLL scores are statistically and positively correlated with value-added estimates—more so in math than in other subjects. The strongest links are in the areas of “systems leadership,” which includes practices like “establishing and implementing expectations for students and staff” and “ensuring a high-quality, high-performing staff”; and “professional and community leadership,” including attributes such as “shows professionalism” and “supports professional growth [of staff].”

The results are mostly driven by principals with at least three years of tenure at their schools; none of the links between FLL and value-added were significant for principals with one or two years of school tenure. This is presumably because, as other studies have shown, it can take multiple years for principals to make a concrete impact on schools.

It’s encouraging that the practices and behaviors of principals as measured by a tool actually link to student achievement. Perhaps studies like these will help us to define empirically what we mean by principal quality. That’s been a black box for far too long.

SOURCE: Moira McCullough, Stephen Lipscomb, Hanley Chiang, and Brian Gill, "Do Principals’ Professional Practice Ratings Reflect Their Contributions to Student Achievement?," Mathematica (June 2016).

Homeless students in American schools

This report from Civic Enterprises and Hart Research Associates provides a trove of data on students experiencing homelessness—a dramatically underreported and underserved demographic, according to the U.S. Department of Education—and makes policy recommendations (some more actionable than others) to help states, schools, and communities better serve students facing this disruptive life event.

To glean the information, researchers conducted surveys of homeless youth and homeless liaisons (school staff funded by the federal McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act who have the most in-depth knowledge regarding students facing homelessness), as well as telephone focus groups and in-depth interviews with homeless youth around the country. The findings are sobering.

- In 2013–14, 1.3 million students experienced homelessness—a 100 percent increase from 2006–07. The figure is still likely understated given the stigma associated with self-reporting and the highly fluid nature of homelessness. Under the McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act, homelessness includes not just living “on the streets” but also residing with other families, living out of a motel or shelter, and facing the imminent loss of housing (eviction) without resources to obtain other permanent housing. Almost seven in ten formerly homeless youth reported feeling uncomfortable talking with school staff about their housing situation. Homeless students often don’t describe themselves as such and are therefore deprived of the resources available to them.

- Unsurprisingly, homelessness takes a serious toll on students’ educational experience. Seventy percent of youth surveyed said that it was hard to do well in school while homeless; 60 percent said that it was hard to even stay enrolled in school. Vast majorities reported homelessness affecting their mental, emotional, and physical health—realities that further hinder the schooling experience.

- McKinney-Vento liaisons report insufficient training, awareness, and lack of resources dedicated to the problem. One-third of liaisons reported that they were the only people in their districts trained to identify and intervene with homeless youth. Just 44 percent said that other staff were knowledgeable of the signs of homelessness and aware of the problem more broadly. And while rates of student homelessness have increased, supports have not kept pace. Seventy-eight percent of liaisons surveyed said that funding was a core challenge to providing students with better services; 57 percent said that time and staff resources was a serious obstacle.

- Homeless students face serious logistical and legal barriers related to changing schools (which half reported having to do), such as fulfilling proof of residency requirements, obtaining records, staying up-to-date on credits, or even having a parent/guardian available to sign school forms.

Fortunately, there are policy developments that further shine the spotlight on students experiencing homelessness and equip schools to better address it. The recently reauthorized Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) treats homeless students as a sub-group and requires states, districts, and schools to disaggregate their achievement and graduate rate data beginning in the 2016–17 school year. ESSA also increased funding for the McKinney-Vento Education for Homeless Children and Youth program and attempted to address immediate logistical barriers facing homeless students—for instance, by mandating that homeless students be enrolled in school immediately even when they are unable to produce enrollment records. The report urges states to fully implement ESSA’s provisions related to homeless students and offers other concrete recommendations for schools (improving identification systems and training all school staff, not just homeless liaisons) as well as communities (launching public awareness campaigns and collecting better data). In Ohio, almost eighteen thousand students were reported as homeless for the 2014–15 school year. Policy makers would be wise to review this report’s findings and recommendations and consider how to implement and maximize ESSA’s provisions so that our most vulnerable students don’t fall between the cracks.

SOURCE: Erin S. Ingram, John M. Bridgeland, Bruce Reed, and Matthew Atwell, “Hidden in Plain Sight: Homeless Students in America’s Public Schools,” Civic Enterprises and Hart Research Associates (June 2016).

Stronger schools through community organizing

When it comes to reform for urban school systems, effective community organizing is crucial. Community Organizing for Stronger Schools: Strategies and Successes takes an in-depth look at the practice and how it affects schools.

The authors conducted a six-year longitudinal study on eight groups across the United States, all of which had been in existence for at least five years: the Northwest Bronx Community and Clergy Coalition, Oakland Community Organizations, Chicago ACORN, Austin Interfaith, Milwaukee Inner-City Congregations Allied for Hope, People Acting for Community Together, Community Coalition, and the Eastern Pennsylvania Organizing Project. The data sources included: archival documents, adult member survey, youth survey, observations, interviews, teacher survey, public administration data, and media coverage. Dating back to 2003, the study is one of the largest ever to examine the relationship between community organizing and educational outcomes.

Across the sites studied, community organizing was shown to increase awareness of the needs of low-income parents and youth of color. This organizing was characterized by frequent meetings and interactions between organizers and education leaders that typically included discussions around joint reform efforts and implementation.

More district resources were also allocated for low-performing, high-poverty schools, and new policy initiatives echoed the proposals of community organizers. For example, in Philadelphia, the formula for Title I funds was unchanged, Milwaukee kept its commitment to busing poor students in the city, districts in Oakland committed to a ten-year small school creation plan, and $11 million in state funds were publicly invested in the Grow Your Own teacher initiative in Illinois.

All of the sites were successful in organizing campaigns to address school issues like broken escalators and the need for more college counselors. They enjoyed stronger professional cultures, school climates, and instructional cores, as indicated by greater collaboration among teachers, a shift in classroom dynamics, and higher teacher morale and retention. Student outcomes and engagement may have also improved, although the effects weren’t proven to be anything more than mere correlation). At Miami schools supported by People Acting for Community Together, the percentage of students who met reading standards on the Florida Comprehensive Assessment Test rose from 27 percent to 49 percent between 2001 and 2005; supported Oakland schools scored higher on the California Academic Performance Index.

Overall, the findings suggest that community organizing can be advantageous on issues of equity, capacity, and student outcomes in urban school districts. The authors did describe the gains as “tenuous,” however. For example, not all teacher survey measure responses were statistically significant, and some districts were less likely than others to credit organizing for their gains.

Even without strict causation, however, the scale of this study highlights a noteworthy relationship between organizing and a variety of beneficial outcomes. And even though organizers face several challenges, including how to measure their effects, their goal is clear: create lasting reform for urban public school systems.

SOURCE: Kavitha Mediratta, Seema Shah, and Sara McAlister, Community Organizing for Stronger Schools: Strategies and Successes (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press, 2016).