Athletes aren’t America's only Olympic stars

By Chester E. Finn, Jr.

By Chester E. Finn, Jr.

While everyone is fixated on the Rio Olympics and the impressive start that U.S. athletes have made there, it’s worth a brief detour to the results of another summer competition—this one in Hong Kong—in which the American team dominated: the International Math Olympiad (IMO) for high-school students.

More than one hundred countries fielded teams at this year’s fifty-seventh annual competition, including most of those whose students surpass American teens when PISA and TIMSS assess math prowess. And yes, it’s true that Korea, China, and Singapore placed second, third, and fourth in this year’s IMO. But the six Olympians who represented the United States won gold. Nor was this a fluke. The American team came in first last year, too. In fact, with a single exception, it has placed in the IMO’s top five every year since 2000.

Selection for the U.S. team is, in its way, as rigorous as that for the Olympics, and it is conducted through a series of assessments and competitions organized by the Mathematics Association of America.

The six kids who represented the United States in Hong Kong last month are an interesting bunch: Five of them appear to be Asian-Americans, and four attend selective-admission high schools (three private, one public). The other two attend the kinds of suburban public high schools that get high marks from GreatSchools, offer lots of AP and IB programs, and do exceptionally well at college placement.

No doubt these boys have also benefited from some non-school advantages. What’s more, turning around more of our schools won’t, in and of itself, extend all of those benefits to millions more kids. But think about how many more American youngsters could become internationally competitive in math and other subjects if we could pull off such a turnaround. And imagine how many of those would come from other minority communities and disadvantaged groups. It’s worth reminding ourselves that the very best American students—and schools—are pretty darn good. But there aren’t nearly enough of them, and they aren’t nearly diverse enough.

Meanwhile, hearty congratulations to this sextet, and kudos to the Mathematics Association of America for its good work at the pre-college level.

Now back to TV from Brazil.

I had the great pleasure of working with Dara Zeehandelaar and the staff at the Fordham Institute on our recent report, Enrollment and Achievement in Ohio's Virtual Charter Schools. The findings add to the emerging and disconcerting evidence that online charter schools are not serving students well. We found that students who enroll in Ohio’s e-schools tend to be the ones who need the most support and investment—having failed or struggled academically in brick-and-mortar schools—yet they’re faring even worse in these virtual classrooms than similar students in neighborhood schools.

Because of this, we ought to substantially limit the expansion of online charter schools and hold them accountable until they can show that they serve students effectively.

The question, then, is how to improve online learning through experimentation, iteration, and innovation while avoiding the major pitfalls that often plague new implementations of educational technology.

Here are two possible ways forward:

1. Understand that today’s implementation of online learning falls far short of what it takes to offer rich learning environments for children.

I lay out some similar arguments in an upcoming book chapter, but the short version is that new technological developments often allow us to do new things faster and more efficiently. However, the ways in which we structure our use of technology—through our laws, institutions, and the constraints of our human capabilities—largely determine what outcomes we’ll see.

The case of online learning is no different. Fundamentally, online learning allows us to:

These basic features can be employed in a vast array of configurations and for very different aims. For example, take two hypothetical ways that we might employ features of online learning for K–12 students. In scenario one, students are sitting at home alone, clicking through readings and videos at their own pace. Perhaps they complete some problem sets and assignments after each content module, and they have some email interactions with a teacher for periodic feedback. Or maybe they get distracted by other aspects of their day and don’t do any coursework. This scenario is actually quite likely in current versions of online schools.

In scenario two, students access educational content at home through their online school. Their parents are very active in helping them work through material, answering their children’s questions and guiding them through problem sets. Maybe there is a school campus where students can visit teachers for personal attention a few times each week. And the students augment their content learning with extra activities and learning experiences that their parents set up on their behalf.

It’s easy to see which environment is likelier to provide a rich learning experience. The second scenario is also much more difficult to orchestrate, as it demands that parents work side-by-side with teachers and the community. Both scenarios involve online schooling. But it’s the configuration of resources—social, instructional, and cultural—surrounding the learner that will amplify the positive aspects of online learning (having access to content as one part of a holistic learning experience, for example) instead of the negative ones (merely using online content as a replacement for learning experiences).

While the potential of online learning is enticing, using its current form as a general replacement for brick-and-mortar schooling probably sets us up to fail. As many educators and researchers can attest, school is a vastly more complex social, cultural, and institutional environment that goes beyond merely presenting content to students. While we’re making strides in designing better online learning over time, online schooling still has a ways to go. And the question of what form online schools should take remains an open one.

2. Uncritical expansion of any new educational technology is likely to exacerbate inequality, not fix it. Assume this, and create ways to experiment with new innovations in a measured way while mitigating exploitation and negative consequences.

Technology researcher Kentaro Toyama observes that technology doesn’t change education as much as it amplifies whatever existing forces are already present. So what forces are getting amplified by online charter schools in Ohio?

Current online forms of schooling are likely to promote more didactic and passive learning experiences, such as lectures and the consumption of visual media. In Ohio, charter schools are intended to be an alternative to the traditional school system, and they primarily serve needy and underserved student groups. Even if both are created with good intentions, this unique combination of technology (online schooling) and governance (charter school regulations) unfortunately has the potential to extend limited forms of pedagogy to students who need richer learning supports.

The frequent result is that learners most in need of support are ineffectively served by technology. Certain actors (such as companies and providers) will profit in the short term from increased investment. Existing inequalities in our education system will be amplified, and outcomes for learners will be mediocre or negative.

If we begin with the assumption that uncritical implementation of technology will exacerbate inequality, what should we do? One knee-jerk reaction is to avoid anything new out of fear that we’ll hurt students. A more nuanced way forward would be to always think critically when arriving at the intersection of policy, technology, and pedagogy. As a rule of thumb, I naturally gravitate to the question of what good learning looks like. Returning to this question can also provide guideposts for future policy, as well as what innovations researchers and entrepreneurs should strive toward.

For example, when I think of what makes for rich learning, I see:

It’s not difficult to see that what online schools often provide—content via a computer screen and network connection—only constitutes a small slice of what is needed for rich learning experiences. Operators and designers of online schools need to consider how the other aspects of rich learning can be facilitated.

In my own work with school districts and educators, we are learning that online coursework has benefits like opening up access to content. But merely sitting students in front of that content leaves much to be desired. Students continually seek meaningful activities and interactions with their teachers and peers. This last statement is a good litmus test when we’re designing new education systems that utilize online learning.

Iterative and continued innovation in this space should always address the question of whether we’re providing meaningful experiences for students, as well as whether we are expanding their interaction with expert teachers and supportive peers. Online tools (and maybe, in time, online schools) have a role to play in that vision. We should encourage critical thinking about how technology, policy, and pedagogy intersect—and invest in pilot projects to build up our knowledge base of what works and in what conditions. Finally, we should avoid combining new technologies with governance and policy decisions that uncritically expose our most vulnerable learners to untested programs.

June Ahn is an associate professor at New York University. He is the author of the recent Fordham Institute report Enrollment and Achievement in Ohio’s Virtual Charter Schools.

On this week’s podcast, Mike, Robert, and Alyssa rumble over reform as a street fight. During the research minute, Amber Northern examines whether a school’s value added is indicative of principal quality.

Hanley Chiang, Stephen Lipscomb, and Brian Gill, "Is School Value Added Indicative of Principal Quality?," Mathematica (June 2016).

A new Education Next article examines the impact of New York City school closures on a variety of student outcomes, including graduation rates, attendance, and academic performance.

Analysts studied twenty-nine high school closures announced between 2003 and 2009, analyzing outcomes for over twenty thousand affected ninth graders in several groups: those who were just beginning their ninth-grade year when closure was announced (called the “phase-out” cohort); those who chose to stay after the closure announcement (the “phase-out” process allowed them to stay until their expected year of graduation); those who transferred elsewhere; and those rising ninth graders who were required to attend a different high school because of closure. The schools in the treatment group slated for closure were, as you would expect, among the lowest-performing in the city. (Another group of high schools that exhibited both similar poor performance and similar low-achieving students served as the comparison group, although it was not clear why they weren’t slated for closure.)

Analysts first predicted the impact of the closure decision on graduation rates for the “phase-out” cohort. They found small but statistically insignificant differences, concluding that the phase-out process did not negatively impact graduation rates or make a clear impact on credits earned, Regents exams passed, or attendance.

Next they examined impacts on those who remained in the closure schools during the phase-out process and found that they were more likely to graduate high school; yet on most other indicators (such as attendance and credits earned), student improvement was similar to that in the comparison group. For students who transferred from their ninth-grade school to another city high school before the end of their twelfth-grade year, there were no significantly different patterns in outcomes among the treatment and comparison students.

Finally, they examined the trajectory of those students who would have been assigned to one of the closure schools but weren’t; instead, they were made to attend a different high school than the one targeted for closure. This group comprised roughly eleven thousand eighth-grade students who lived in neighborhoods or attended middle schools that fed into the closure schools and who had backgrounds similar to those who had previously attended the closure schools. It was found that they generally enrolled in higher-performing schools and performed better there. Specifically, the closures improved graduation rates for displaced students by 15.1 percentage points compared to the comparison group; they also improved the rates of students receiving Regents diplomas and boosted ninth-grade attendance.

Analysts conclude that “this is compelling evidence that students benefited from having a low-performing option eliminated from their high school choice set.” We’re accumulating robust evidence that closing low-performing schools has the potential to improve educational outcomes, even though it can be emotionally draining for the impacted students, parents, teachers, and larger community. Perhaps, like the breakup of a dysfunctional romance, we need to focus on the longer-term benefits of school closure rather than the immediate heartache and nostalgia for the past.

SOURCE: James J. Kemple, "School Closures in New York," Education Next (August 2016).

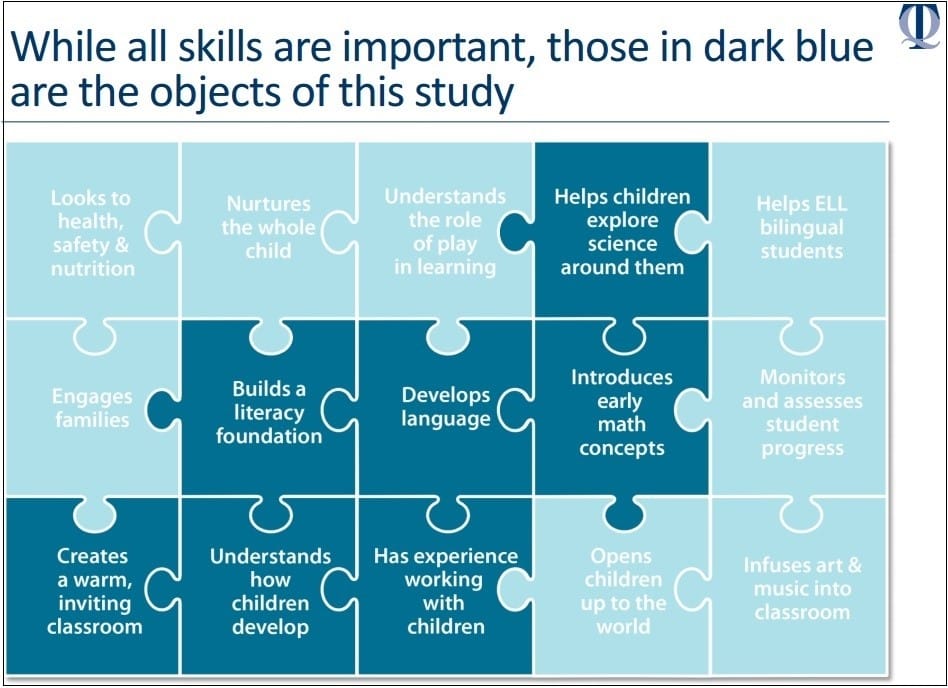

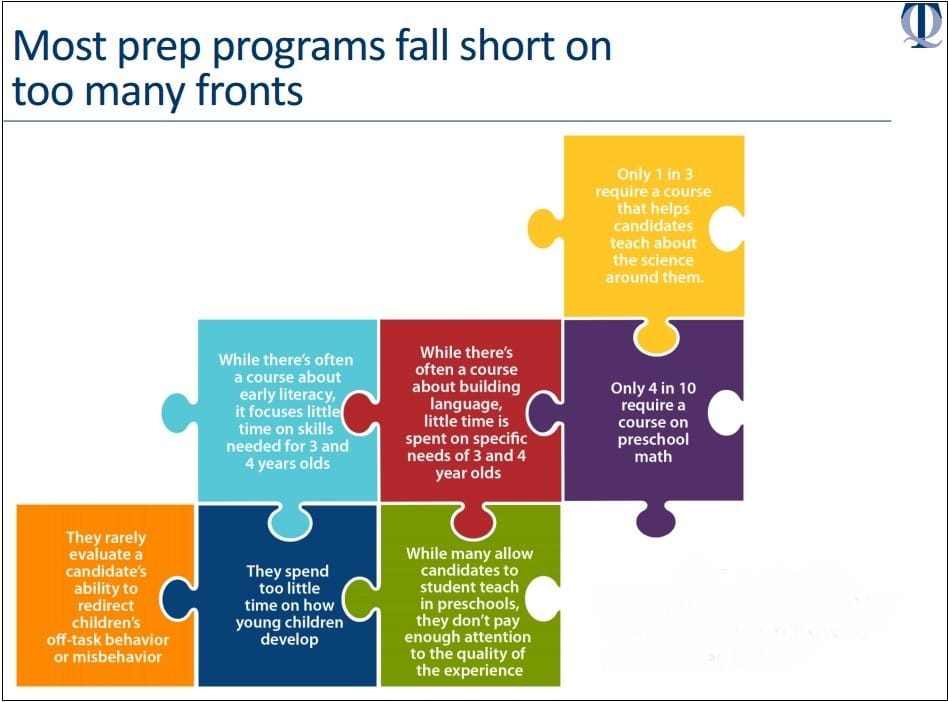

The National Council on Teacher Quality (NCTQ) recently reviewed one hundred of the nation’s pre-K teacher preparation programs, attempting to answer whether pre-K teacher candidates are being adequately prepared for effectiveness in their future jobs. The answer is, largely, no.

The programs spanned twenty-nine states that certify pre-K teachers, most of them offering bachelor’s and master’s degrees. They reviewed course requirements and descriptions, course syllabi, student teaching observation and evaluation forms, and other course materials required for degree completion.

The bottom line, reported NCTQ, is that most of the programs spend far too much of their limited time focusing on how to teach older children rather than on the specific training needed to teach three- and four-year-olds. Some specific findings are neatly summarized in the following slides from NCTQ:

NCTQ recommends, among other things, that states narrow their licensure to certify educators to no more than the years between pre-K and third grade, rather than treating pre-K as a part of a broader elementary teaching credential; that they encourage teacher preparation programs to offer either more specialized degrees or early childhood education as an add-on endorsement; that they ensure that preparation programs require courses in critical areas such as emergent literacy, early childhood development, or early math and science; and that they encourage future pre-K educators to do their student teaching with highly effective preschool teachers.

All good suggestions, but also heavy lifts, especially for a states whose teacher preparation programs aren’t so hot to begin with.

SOURCE: Hannah Putman, Amber Moore, and Kate Walsh, “Some Assembly Required: Piecing Together the Preparation Preschool Teachers Need,” National Council on Teacher Quality (June 2016).

Charter school performance is a mixed bag: some charters outdo their neighborhood district schools, others show no difference, and some do worse. A new Mathematica meta-analysis attempts to identify the characteristics common to each of these groups. What, in other words, makes a high-performing charter schools so effective?

As author Phillip Gleason notes, it is difficult to carry out studies of this nature. Much of the data are based on observation, so determining causation is essentially impossible. Observation also takes time and costs money, which usually necessitates small sample sizes. And many of the “practices” being studied are abstract concepts, such as principal quality, that are difficult to measure quantitatively and objectively.

To mitigate these impediments, Gleason compiled seven studies that used different methods—including observational study, survey administration, and lottery-based designs (comparing students who won a spot via charter lotteries to those who did not)—to study charters schools around the country. The sample sizes in each of these studies range from twenty-nine to seventy-six schools.

Three charter characteristics were found to be linked to high student achievement in many studies (therefore showing a ‘strong association,” according to Gleason—a term he never defines quantitatively): longer school days and/or school years; a consistent and comprehensive behavior policy (with both rewards and sanctions); and prioritizing greater academic achievement (in lieu of other objectives, such as building self-esteem).

To my eye, however, all of this is seems rather intuitive. It’s easy to understand, for example, how schools that strive for student achievement above all else will more readily reach those heights. The same goes for more extended learning time and charters with stringent discipline policies, where disruptive students are more readily removed from the classroom.

Nevertheless, other practices were moderately related (also not defined quantitatively) to greater achievement in charter schools, including frequent coaching of teachers, using student data to drive instructional interventions, and “high-dosage” tutoring. Although Gleason does not discuss these practices in depth, perhaps their weaker links to success can be explained by the need for quality over quantity in the case of all three.

Finally, Gleason’s review found many characteristics with little or no relationship to charter achievement, among them: teacher qualifications, school funding, and affiliation with a charter management organization. Gleason is careful to note, however, that these finding don’t disprove those variables as drivers of change. Instead, what’s needed is more exact research to obtain a clearer picture of what drives charter success.

Overall, the meta-analysis doesn’t discuss many things reformers don’t already know, or strongly intuit. It does, however, present a concise, comprehensive review that boiled down many complex studies into clear patterns.

SOURCE: Philip Gleason, “What's the Secret Ingredient? Searching for Policies and Practices that Make Charter Schools Successful,” Mathematica (July 2016).