Editor’s note: This essay is an entry in Fordham’s 2021 Wonkathon, which asked contributors to address a fundamental and challenging question: “How can schools best address students’ mental health needs coming out of the Covid-19 pandemic without shortchanging academic instruction?” Click here to learn more.

I found my husband sitting in a plastic Adirondack chair in our backyard, cigar in hand, the flames of the fire pit licking his feet.

“What are you doing?” I asked in confusion.

“I’m happy,” he smiled.

The image of him content and voluntarily spending time in nature perplexed me. We are a house of long hours and dirty dishes, of off-key piano tunes, whirlwind strewn toys, and shrieking children costumed as sequined rock star or sword-wielding knight. We are not calm starlit hours by a fire.

I investigated the incongruence. “I’m free,” he said of his newfound happiness, “and I’ve found a place where I buy in.”

He referenced his decision to walk away from the public school system where he had labored for thirteen years, to slash his salary and feed his soul in a new role at a private classical school.

The scene painted the mental toil an authoritarian, utilitarian school system exacts on both teachers and students. It pointed me to an unrealized benefit of classical education: transcendent beauty that stirs the heart, challenges the mind, and lifts spirits to dwell on concepts greater than self.

Substance in education matters to mental health.

The focus on how to teach reading or math, the obsession with STEM offerings at the cost of decimating basic civic understanding, may have allowed students and teachers to limp through the public school system in past years. But reintegrating students into schools after a year of personal loss, learning loss, and loss of trust in institutions requires more. It requires drawing from the whole depth of wisdom in the classical canon.

The devastating realities of the past year cannot be erased by reading Homer or Shakespeare; students and teachers have experienced trauma not easily soothed by any means. But students and teachers in both private and public schools who go to the fountains of classical literature, history, and theology find predecessors in struggle and resilience who offer hope for our dark days.

As Tolkien writes in Mythopoeia:

“They have seen Death and ultimate defeat,

and yet they would not in despair retreat,

but oft to victory have turned the lyre

and kindled hearts with legendary fire,

illuminating Now and dark Hath-been

with light of suns as yet by no man seen.”

An attempt to pierce students’ veils of depression, grief, and anger with the “light of suns” found in the Western cannon may seem unhinged from their practical needs. However, if education is an inheritance, we owe students the gifts and lessons of the thousands of generations before us. Just as we would learn from flawed physical inheritances—a propensity toward alcoholism, a family estate saddled with debt—and perhaps choose wiser, so students can learn from the flawed intellectual inheritance of Western civilization. From people who have fought valiantly, despaired completely, and rose triumphantly, students can glimpse strategies for walking through their own darkness into light.

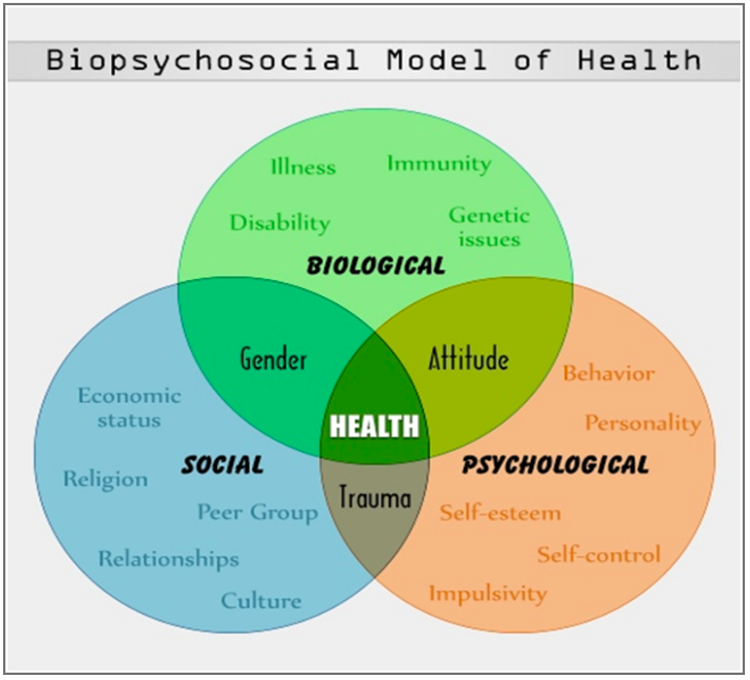

This substantive richness can even make students better learners, as counterintuitive as it might seem that a focus on content would improve study skills. However, psychology researchers found that students with a transcendent purpose for learning were more likely to show academic self-regulation, choosing to study when they would rather be doing something else.

And a Notre Dame study confirms that the benefits of classical education on mental and emotional health extend into adulthood, finding classically educated students scoring far higher on positive life outlook metrics than students with any other educational background.

In part, these positive outcomes flow naturally from the experience of awe inherit to the classical focus on the sublime. Dacher Keltner, psychologist and pioneer of awe-related theory, describes the mental health benefits of experiencing awe, “Awe is a positive emotion triggered by awareness of something vastly larger than the self and not immediately understandable—such as nature, art, music…” Keltner says. “Experiencing awe can contribute to a host of benefits, including an expanded sense of time and enhanced feelings of generosity, well-being, and humility.”

When we replace small curricula—fragmented works of literature scattered in textbooks, standardized test reading passages devoid of context—with grand whole works of literature, we give students the opportunity to stand in awe. We enhance the wonder when we present them great works of art and music, balanced with the unraveling of the universe’s mysteries in math and science.

Not only does this classical approach to teaching and learning give students a grasp of the arc of the moral universe—and the analytical skills to decide whether it bends towards justice—but it positively impacts their mental health. As Keltner indicates, standing in awe promotes emotional well-being.

Referencing Dr. King’s famous line brings us to a primary objection against classical education: advocating this method as a mental health support during a time of racial strife may seem tone deaf. After all, why foist the words of dead white men upon diverse classrooms? Vocal reformers boast of disrupting texts and ridding classrooms of such influence. But some Black educators assert that classical education has been a precursor of many steps toward equality, lifting people from oppression and feelings of hopelessness and empowering them to work for change.

“In reading the human stories of Odysseus or Achilles, the mind dark with hopelessness finds the light of hope to fight for freedom and to reason on how to fight the battle against oppression,” writes professor and classical school founder Dr. Anika Prather, who works to engage African American students with classic texts.

In fact, MLK’s stirring Letter from a Birmingham Jail is replete with classical literature references. In that dark moment, MLK encouraged and rebuked others with the words of Homer, Augustine, Aquinas, Luther, Lincoln, and other great thinkers. Students may feel that they have been in prisons of their own this past year, kept inside away from friends and extended family. We owe them the freeing words of not only MLK but of the great writers that fed and empowered him.

While a classical curriculum cannot soothe all the harm that students have experienced over the past year, this original “social emotional learning” of virtue and wisdom provides a foundation for emotional recovery from which other efforts can build. Understanding that their steps follow the paths of trial and triumph blazed by those who preceded them, students can grasp emotional resilience to help them face current challenges and difficulties to come.