Identifying "what works" is still a work in progress

If we are going to take advantage of the End of Education Policy, and usher in a Golden Age of Educational Practice, we need our field to start taking rigorous evidence much more seriously.

If we are going to take advantage of the End of Education Policy, and usher in a Golden Age of Educational Practice, we need our field to start taking rigorous evidence much more seriously.

If we are going to take advantage of the End of Education Policy, and usher in a Golden Age of Educational Practice, we need our field to start taking rigorous evidence much more seriously. Getting inside the black box of the classroom is a necessary first step, and launching lots more research initiatives about teaching and learning is second. But the big payoff will come if we can more accurately and constructively identify “what works” (and when it works, and what it costs)—and get it implemented more widely across the country.

That’s not a particularly revolutionary notion. People have been trying to figure out what works in education for at least fifty years. But we still haven’t come close to cracking this nut, and if we want to make progress, we need to figure it out. Below I offer some of my ideas on how to do so. In future posts I’ll tackle the much tougher question of scaling up evidence-based practices in the real world.

***

There are many debates in education policy that will never be settled by science because they mostly involve values, priorities, and tradeoffs. (Should parents get to choose their children’s school, and if so, should religious schools be in the mix? How much should we spend on education versus other activities that compete for our limited resources? Should our schools focus equally on preparation for college, or career, or citizenship?) Evidence can inform policy debates, but it is hardly dispositive.

Instructional practices, on the other hand, are different. Or should be. Consider elementary schools, those magical places where we work to turn pre-literate, pre-numerate kindergarteners into avid readers, writers, and problem solvers, ready to tackle the Great American Novel in middle school, capable of writing a clear five-paragraph essay, and possessing a mastery of math facts and an early understanding of algebraic reasoning.

None of this is controversial. Everyone agrees that all students need to have these basic skills, none of which come naturally to the human animal, and all of which must be taught to them in school. But this stuff is complicated. Questions of practice that elementary educators must address include ones such as:

For all of these specific skills and processes, science can help us understand what’s happening inside kids’ brains when it’s working, when it’s not, and what that implies for specific instructional practices. To be practical, we also need to understand what works in a classroom setting. All of this is surely easier to do one-on-one, between a single teacher and a single student, but we can’t afford to employ 25 million tutors for our 25 million elementary-age students. That brings us into questions like these:

The best part about these questions is that their answers are knowable. In an ideal world, it would go something like this:

This is how it works in other fields, most notably medicine. It doesn’t go perfectly. Doctors still debate vociferously about various approaches to treating certain illnesses, and the medical field worries about the long time-lag between the publication of evidence-based practice guidelines and their widespread use. (One study put it at seventeen years on average!) Still, most of the components are in place, and it is one reason why we continue to get better at treating illnesses.

I have a book on my desk from the American Academy of Pediatrics, Pediatric Clinical Practice Guidelines and Policies, 14th Edition. These folks serve the same kids that our teachers and administrators do. And on a wide range of topics, from Attention Deficit Disorder to Diabetes to Sinusitus and beyond, they have a set of clinical practice guidelines that professionals have endorsed and expect to be followed. All based on rigorous studies, and which form the basis for medical education. They don’t expect doctors to figure out treatments for these illnesses on their own. They don’t expect doctors to Google “Sinusitis,” or turn to Pinterest, like so many of our teachers do.

I understand that plenty of people don’t like the medical analogy. Teaching is an art and a science, goes the argument. Fair enough. Cognitive scientist Dan Willingham prefers to point to architecture. There is a lot of art in architecture, a lot of freedom, different styles and approaches and traditions. But there are also a set of engineering principles that architects simply cannot ignore, not if they don’t want their buildings to fall down.

So too in education. There will always be, and should be, a lot of room for creativity and artistry in teaching, and a wide range of approaches, from Montessori to classical models and beyond. But there are also some design principles that cannot be ignored, not if we don’t want our children to fall behind.

The teaching of foundational reading skills is one of those areas. It’s crazy that, twenty years after the National Reading Panel report, we still have teachers who believe that kids learn to read naturally, just as they learn to speak—and that education schools are still teaching that! (Not that it’s easy to get experts to agree on what precisely the research says on the topic.) It’s like architecture professors positing that gravity is just a theory.

Surely there are a handful of other areas where strong research studies can guide instructional practice. So let’s begin there. Why don’t we have a professional organization producing “Clinical Practice Guidelines and Policies” for education, ones that would be embraced by all educators and enforced by the profession?

It wouldn’t need to start from scratch. In recent years, the federal What Works Clearinghouse has published some excellent “practice guides,” which come close to this vision. But they have no buy-in from the profession, nor do they have any teeth. It’s hard to know if anyone is reading them, much less using them. A recent IES “listening tour” does not provide much optimism on that front.

Turning back to elementary schools, there’s an opportunity. An accident of history has bequeathed us no professional association for elementary school teachers. So let’s create such a group, one with a membership among elementary school teachers, principals, and instructional coaches. Its board should be comprised of accomplished educators and respected scholars and other practitioners; the Americans involved in ResearchED might be a good place to look for initial leadership.

Then philanthropists could get such a group off and running on developing a set of evidence-based practice guidelines, limited to the few areas with the strongest research. This organization might also partner with companies that administer state licensure tests to revise the assessments to align with their recommendations. Here, too, the idea isn’t to invent something out of whole cloth; Massachusetts’s test for prospective teachers has covered much of this ground, especially around early reading, for years.

***

To be sure, this still doesn’t solve the problem of getting better practices in use in our classrooms. It was more than thirty years ago that the U.S. Department of Education, under the leadership of Bill Bennett and Chester Finn, published the first “What Works” guides. Much of what they identified is still legitimate today, but is also still widely ignored in our schools. Flagging evidence-based practices is clearly just half (or a quarter, or an eighth?) of the battle. We also have to convince the field, especially ed schools, to value evidence over ideology and beliefs, plus we have to battle what educator Peter Greene recently called “the thirteenth clown problem”—the challenge caused by shady vendors hawking various educational products as “evidence based” even when they clearly aren’t.

I’ll offer ideas on how to overcome these significant barriers in future posts. But just as better research on classroom practice is dependent on better data about classroom practice, so is the implementation of evidence-based practices dependent on our ability to identify what is evidence based and what is not. We have bits and pieces of that today. We need the whole enchilada.

Recent weeks have seen multiple efforts to declare and prove that the United States has entered a post-policy era, complete with multiple references to Francis Fukuyama’s famous 1992 book, The End of History and the Last Man. As you may recall, Fukuyama suggested that the Berlin Wall’s fall and end of the Cold War signaled the triumph of western-style liberal democracy and a conclusion—even a happy finale—to the various struggles and conflicts that came before.

Fast forward to today. Washington Post columnist Megan McArdle cited a dinner companion who declared that “Policy is dead.” She went on to comment that policymaking in Washington has “ground to a halt” in general. On the rare occasions when anyone is moved to try to do something, she wrote, “They’re interested in talking points that flatter the folk beliefs of their base, and if the data contradicts voter opinion, they’d rather do the wrong thing than the unpopular one….Actual legislation, the kind that provides novel solutions to new problems, is generally dismissed as impossibly ambitious.”

Last month, my colleague Mike Petrilli devoted 1354 words to “The End of Education Policy,” wherein he argued that “Our own Cold War pitted reformers against traditional education groups; we have fought each other to a draw, and reached something approaching homeostasis. Resistance to education reform has not collapsed like the Soviet Union did. Far from it. But there have been major changes that are now institutionalized and won’t be easily undone, at least for the next decade.”

Thanks to that “institutionalization,” Mike believes, combined with present political stand-off, there remains no real appetite for more major policymaking in the foreseeable future, nor any clear path forward on the issues that might benefit from it, so we should redirect our energies to the challenges of implementation and educational practice. He yearns for a “Golden Age of Educational Practice” and urged his readers to take the lead in bringing that about.

Neither McArdle, referencing federal policy, nor Petrilli, confining himself to education, is exactly wrong. Partisan gridlock in Congress and mishigas in the White House have made it extremely hard to get anything major done in today’s Washington, and something similar can be seen in a number of states. (It’s not impossible, though, even on Capitol Hill: Working in bipartisan mode, Senators Lamar Alexander and Patty Murray shepherded both ESSA and the Perkins Act to successful reauthorization in the past few years, complete with significant policy changes.) Most of the big policy shifts of recent decades—more choice, more accountability, higher standards—are, as Mike says, not going away, and sizable implementation issues certainly remain to be worked through. Plus, he acknowledged, some policy tussles remain: “battles in state legislatures between reform advocates and their opponents, and sometimes little skirmishes in Congress.” He characterized them, however, as “small ball.”

I beg to differ. Big, heavy medicine balls are rolling around—they weigh too much to hurl—every time Maryland’s Commission on Innovation and Excellence in Education meets in Annapolis. I’ve been part of that group for more than two years now—I’m a mite weary of it, to be honest—and we’re dealing with issues of enormous policy consequence for the Old Line State: what it means to be a high school graduate, how to weigh CTE versus college, whether to construct a career ladder for teachers, how to define poverty, whether it’s more important to provide pre-school for deeply disadvantaged three-year-olds or to widen the pre-K net for four-year-olds, how to ensure accountability for reforms at the district level, and much more.

It’s “only” a commission, to be sure, and its “only” one state, but if we can roll any of those balls as far as state lawmakers, they’re going to face much heavy policy lifting of their own: whether, how much, and in what fashion to raise taxes so as to invest more in education; whether to compel any corresponding cost savings, such as expanding class sizes, for which the current statewide public-school average is 20.46 students; whether to construct new governance mechanisms to develop a coherent CTE system and oversee the whole reform initiative; and much more. Plus they must try to deal with this in a fraught political atmosphere, in which Republican Larry Hogan sits in the governor’s office while Democrats enjoy a veto-proof majority in the General Assembly.

Education policy surely isn’t dead in Maryland. It’s not even dead on the State Board of Education, where I’m nearing the end of my time. There, we’ve been hassling with whether and how to assign ratings to the state’s public schools as part of the ESSA accountability system (we settled on one to five stars), whether to allow districts to hire exceptional leaders who aren’t career educators to serve as superintendent (my side lost that one!), what to do with gifted students, what to do about equity, how to overhaul teacher preparation, what (if anything) to do about school choice in a state that has little of it, and plenty more. The board also works amid intense politics, including a well-worn route to the legislature that is regularly trod by established adult interests who don’t want us to change anything at all!

No, policymaking is alive in Maryland and, though not exactly healthy, is certainly breathing, flexing some muscles, and recoiling when sensitive parts of its anatomy get pinched.

Something similar is underway in Ohio, where my Fordham colleagues struggle against established interests over school funding, school choice, charter-school accountability, the pushback against testing, and the widespread and politically potent impulse to let kids get diplomas, even when they fail to meet the respectable academic standards the state set just a few years back.

True, more of what we see in Ohio is defensive, the kind of reform preservation that Mike acknowledged, while more of what I’m part of in Maryland are efforts to break new ground. But neither place has reached anything akin to the end of policy, even if Uncle Sam has stumbled to a temporary stop. It never hurts for us Beltway types to recall that states are where the founders placed, if only by default, responsibility for education. In many of their capitals, and in many localities, policymaking is actively underway, whether or not one savors the outcome. Indeed, I don’t believe it ever ends, not in this country, not in education, not in my lifetime.

In April, we published a report by Andrew Saultz and colleagues—along with an interactive website—that mapped the locations of “charter school deserts” across the country. These are high poverty areas that could use additional options for disadvantaged students but nonetheless lack charter schools. The website enables users to look at every neighborhood in the country to identify underserved areas. And from the looks of it, journalists, education wonks, and curmudgeonly teachers alike took advantage of the unique opportunity to eyeball their neighborhoods and come to their own conclusions. We also heard from charter operators who used the map to identify areas ripe for expansion.

We were pleased to see all of that. But one critique we received was that the map did not show the locations of private schools—obviously a critical additional “option” for poor kids, particularly so in the areas that operate private school choice and tax-credit scholarship programs. So with a little help from our friends at the American Federation for Children, we’re back with an updated map that includes not just traditional and charter public schools, but private schools as well. Using data from the U.S. Department of Education’s Private School Universe Survey, we “geolocated” every private school in that dataset—which comprises 81 percent of them—and plotted each on the map. With this update, users can now identify the private schools in their neighborhoods, and areas that lack not only charter schools but private options as well.

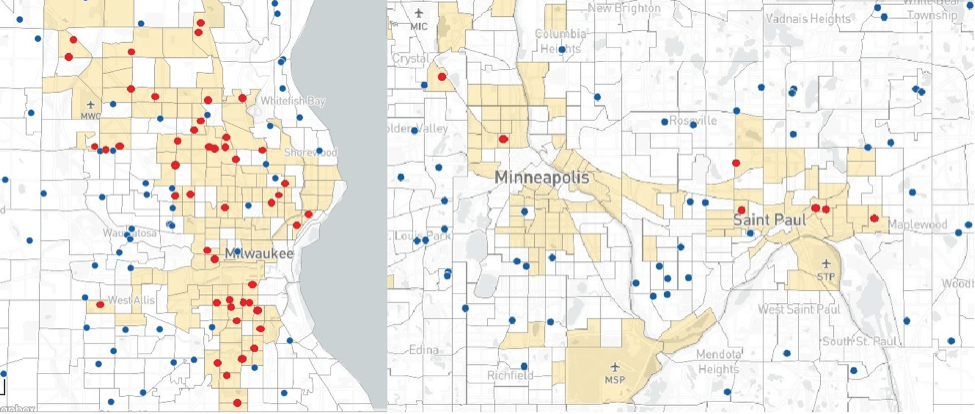

Of particular interest to those who support private school choice is whether voucher and tax-credit scholarship programs serve as oases in the charter school deserts on our map. And indeed, there’s evidence that they do.

Consider the contrast between Milwaukee and the Minneapolis-St. Paul metro areas represented in Figure 1. Milwaukee has one of the nation’s oldest voucher programs, beginning with legislation passed in 1990, as well as a statewide voucher program in Wisconsin. The Twin Cities areas are bereft of these programs. Just as one might expect in a city with a broad and longstanding voucher program, Milwaukee’s private schools appear to be serving diverse populations, with some located in the suburbs, but many also operating in high-poverty charter school deserts.

In the Twin Cities, the picture is much different. Despite having large swaths of high-poverty charter school deserts, very few private schools are located in them.

Figure 1: Milwaukee has private schools serving many types of neighborhoods, but the Twin Cities area has few private schools serving high-poverty charter school deserts

Note: The shaded areas are charter school deserts, which are areas with high poverty and no charter schools. The dots on the map represent private schools. Red dots represent private schools falling in charter school deserts, and blue dots denote those outside the deserts.

Many of the private schools in Milwaukee’s charter school deserts have opened since the city’s voucher program was initiated in the early 1990s. For example, St. Joseph Academy, which serves neighborhoods in high-poverty southern Milwaukee, began as a Catholic day care, but since 2009 has expanded to provide an elementary school serving 312 students in pre-kindergarten through fourth grade, according to U.S. Department of Education data. In recent years, the school has expanded to serve middle schoolers, too.

Of course the existence of private schools does not guarantee access. Admission policies, low voucher amounts, and enrollment caps all impact entry. But in cities like Milwaukee, voucher programs appear to be increasing choices for students in high-poverty areas by helping private schools to thrive and enabling new schools to open in the neighborhoods that need them the most.

I owe Education Gadfly readers an apology. Dylan Wiliam’s excellent and eminently sensible book was published nine months ago and has been sitting on my desk since then. Don’t make the same mistake I did. Creating the Schools Our Children Need deserves your immediate attention.

An authority on assessment, a former ed school dean, and researcher at ETS, Wiliam is something of an education celebrity in the U.K. and internationally. But he remains comparatively unknown and underappreciated in America, where he has lived on and off for fifteen years. Creating the Schools Our Children Need, which is aimed directly at American readers and written for non-experts, should change that. Wiliam’s goal is to help school board members, administrators, and others who are concerned with raising broadly the performance of U.S. schools to become “critical consumers of research.” His straightforward prose, blessedly free of jargon and unerringly practical, is uniquely well suited to his purpose. “Research will never tell school board members exactly what they need to do to improve their schools,” Wiliam writes, since districts vary too much for the same thing to work everywhere. One of his most trenchant observations is that the reason it is so hard to improve education in America is “because it doesn’t have an education system. It has 13,491 of them.”

He puts forth three proposals about how to think of any ideas that are suggested to improve education. First, he advises, “get away from the idea of what works in education, and instead ask, ‘How well does it work?’” It’s one thing to say, for example, that an intervention is “statistically significant.” If the effect size is tiny, efforts might be better directed elsewhere. (Wiliam is particularly persuasive on weighing the “opportunity costs” of misdirected focus in education.)

Second is that, in evaluating ideas, “we also need to take into account the cost of interventions.” For example, class size reduction might work and often does, particularly in early grades, but its effectiveness depends on the availability of large numbers of strong teachers—and it’s very expensive. “Costs and benefits are meaningless if studied separately,” Wiliam explains. “Any educational policy needs to be evaluated in terms of the balance of benefit to cost.”

Third, it’s not enough to say a policy or program is “evidence-based” unless you’re sure it’s likely to work in a particular district. “This might seem obvious,” he observes, “but many educational innovations work in small-scale settings but when rolled out on a wider scale are much less effective.” As Wiliam notes early in the book, “Everything works somewhere; nothing works everywhere.” Given our propensity to follow fads—and follow them off a cliff—this is a worthy mantra for American education. Let’s hope it sticks.

Lest you get the impression that Wiliam is an education Eeyore, glumly insisting nothing works, or works well enough to justify the cost, the final section of Creating the Schools Our Children Need cites “two things that can improve educational achievement substantially, and with little additional cost.” The first is a knowledge-rich curriculum; the second is improving the teachers we have (not the teachers we wish we had).

Anyone looking for a quick explanation in layman’s terms of why it’s a fool’s errand to fetishize “Twenty-First-Century Skills” such as critical thinking and problem solving must read Professor Wiliam on the subject. “The big mistake we have made in the United States, is to assume that if we want students to be able to think, then our curriculum should give our students lots of practice in thinking,” he writes. “This is a mistake because what our students need is more to think with.”

He is equally clear-eyed on efforts to improve teacher effectiveness. We are not very good at predicting who will be an effective teacher, Wiliam points out. Neither are we as good as we think at identifying good and bad teachers through things like observations, surveys, or test scores. “For the foreseeable future, improving teacher quality requires investing in the teachers we already have,” or what Wiliam calls the “love the one you’re with” strategy: Almost all teachers, he insists, can reach elite levels of performance if they work hard at it for ten years. The key is creating a culture of improvement and focusing their improvement efforts on the things that benefit students most. “And the available research evidence suggests that is using assessment to adjust instruction to better meet students’ needs,” he concludes.

Ever since hearing him speak at one of the first U.S. ResearchED conferences, Dylan Wiliam has been on my radar screen. Please forgive me for taking so long to put him on yours.

SOURCE: Dylan Wiliam, Creating the Schools Our Children Need: Why What We're Doing Now Won't Help Much (And What We Can Do Instead) (Learning Sciences International, 2018).

A recent Pew Research study found that by 2016, half of all Millennial women—those born between 1981 and 1996—were mothers. And as we in the education reform business keep working to make schools better for future generations, we should be paying attention to what this generation’s parents say about schools right now. That’s why the Walton Family Foundation and Echelon Insights, a Virginia-based data analytics firm, partnered to conduct a survey of what millennial parents think about schools and their children’s education.

To help determine what questions to ask a broad sample of these parents, researchers first conducted focus groups with millennial parents in three cities (Orlando, Minneapolis, and Richmond) to learn about their dreams for their kids and what they expect from their local schools. Armed with these insights, they wrote and administered a survey to 800 millennial parents, a nationally representative sample, with questions covering five themes: (1) How are schools doing? (2) What should schools be doing? (3) How can we measure how students are doing? (4) How can we measure how schools are doing? (5) How should we hold schools accountable? The results are broken down by demographic factors like race, gender, and yearly income.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the most influential factor driving parents’ ideas about education is income. In almost every category, vast differences emerged between parents making less than $30,000 per year and parents making more than $75,000 per year. Most notably, low-income families are much less likely to be satisfied with America’s schools (44 percent, compared to 81 percent of high-income parents). The results are similarly divided between different levels of educational attainment: only 49 percent of parents with a high school diploma or less believe kids are getting a good education, while 74 percent with a bachelor’s degree believe so.

What is “a good education”? There was little consensus among respondents. A plurality (38 percent) selected, “To prepare students for further learning, like college or trade school.” A close second (30 percent) was, “To prepare students for the workforce so they can succeed in a career and make a living.”

Parents were also asked to rate the importance of seventeen academic, social, and workforce skills. “Be able to get and keep a job” tops the list, with an average score of 8.54 out of 10. Right below that are, “Be able to handle their personal finances,” and, “Be able to read at a twelfth grade level.” However, social skills like self-confidence and goal-setting were ranked almost as highly, and parents say they rely on schools to teach those as well as academic skills. The report does not specify whether this view varies between demographic groups.

Millennial parents also use a variety of data points to measure how their students and schools are doing. A majority (56 percent) say they rely primarily on course grades to monitor their students’ proficiency in reading, and 40 percent rely on grades to monitor math proficiency. They also place significant weight on conversations with their child’s teachers. When asked what else they would like to know, parents expressed the need for more specific information about what their child struggles with in the classroom. When it comes to finding a good school, millennial parents most often rely on test scores (53 percent), school culture (42 percent), and extracurricular activities (40 percent).

The income divide shows up again here. Fewer than half of low-income parents believe they have useful information about their child’s progress; they would rather know about a school’s graduation rate. High-earning parents wanted to know how their child’s performance compared to district and state averages. They also cared more about elective and extracurricular offerings such as arts, music, and sports.

Feelings toward standardized tests were mixed. Thirty percent of parents use test scores as a primary indicator for their own student’s success, but 53 percent use test scores as the primary measure of school quality. And three-quarters of parents want assurance that a passing test score was a guarantee of college readiness and/or scholarship eligibility. (Our recent Grade Inflation study sheds some light on this sticky subject.)

The authors’ main takeaway is that millennial parents expect more from schools than have previous generations. There is a general consensus that while academics are still of primary importance in the classroom, students should also be learning practical and personal skills. The deep divide between high- and low-income families—what they think about their kids’ education and what they expect from their schools—also exposes the need for more research about how we can better communicate with young families of all backgrounds.

SOURCE: “Millennial Parents and Education,” Walton Family Foundation and Echelon Insights. November 2018.

On this week’s podcast, Lindsey Rust, National Director of Implementation for the American Federation of Children, joins Mike Petrilli and David Griffith to discuss whether private schools serve as oases in charter school deserts. On the Research Minute, Amber Northern examines whether parents’ aspirations for their children to go to college someday are affected by receiving new information on the cost, and returns, on completing post-secondary education.

Albert Cheng and Paul E. Peterson, “Experimental Estimates of Impacts of Cost-Earnings Information on Adult Aspirations for Children’s Postsecondary Education,” The Journal of Higher Education (August 2018).