Which states are on a hot streak coming into the 2017 NAEP release?

By Michael J. Petrilli

By Michael J. Petrilli

This post is the third in a series of commentaries leading up to the release of new NAEP results on April 10. The first post discussed the value of the NAEP; the second looked at recent national trends.

Since 2002, federal law has conditioned Title I funding on states’ participation in the biannual administration of the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) in math and reading in grades four and eight. This is a boon to us policy wonks because we can study the progress (or lack thereof) of individual states and use sophisticated research methodologies to relate score changes to differences in education policies or practices. That’s the approach that allowed Tom Dee and Brian Jacob, for example, to inform us that NCLB-style accountability likely boosted math achievement in the 2000s.

Over the years, NAEP has also made stars out of leading states and their governors or education leaders, and has galvanized reformers to try to learn from their successes. It started with North Carolina and Texas, which saw stratospheric increases in the 1990s, especially in math, and across all racial groups. Then it was Jeb Bush’s moment in the sun, as Florida’s scores climbed quickly from the late-1990s through the 2000s, with particular progress for black and Hispanic youngsters. Delaware, Minnesota, and even New York have also produced some big improvements at various times. And let us not forget the Massachusetts Miracle.

The release of the 2017 scores on April 10 will give us fresh data for analyses of this sort. As I warned a few weeks ago, rigorous studies will take time. We should be skeptical of anyone who claims on release day to know why certain states are surging ahead or falling behind—though interesting patterns will surely be fodder for hypotheses and further study.

To help us prepare, Fordham’s research interns and I dug into the NAEP data to see which state-level trends are worth watching. As I’ve argued before, we don’t want to over-interpret short-term changes, so it’s better to look at trends that span four years or more, i.e., trends that are based on at least three test iterations. Here’s a look, then, at statistically significant changes from 2011–15 for every state and D.C. Cells that are empty indicate that there were no statistically significant changes; the numbers represent statistically significant scale score changes from 2011 to 2015.

Table 1: Statistically significant changes on NAEP, 2011–15

National trends are essentially flat over this time period, but that hides much state-by-state variation. Nineteen states, for example, improved their reading results over that four-year period, while just five saw declines. But the opposite is true for math. Scores declined in twenty states, rose in just nine, and were mixed in two.

This table makes it easy to understand why there’s been so much recent buzz about the District of Columbia and Tennessee. But it also suggests that Indiana and Nebraska deserve a lot of love for posting gains in three of the four categories since 2011. And we should also laud Louisiana, Mississippi, and Wyoming for producing statistically significant gains among fourth graders in both reading and math.

But let’s not just look at the leaders; the laggards are interesting as well. Maryland had the worst showing. In 2013, the state got caught for having long excluded many students with disabilities from taking the assessment. Now that it’s properly including these children, its scores have plummeted. But it’s hardly alone; there were plenty of other backsliders, especially in math: Arkansas, Colorado, Delaware, Kansas, Montana, Nevada, and Vermont all saw declines in both fourth and eighth grades. Yikes.

As with the national data, we should be mindful that demographic changes can affect achievement trends, especially as Hispanic students make up an ever-larger proportion of our population. So if we want to understand which state policies and practices might be helping or hurting, we need to find a way to deal with these demographic trends. Matt Chingos and his Urban Institute colleagues offer one clever way of doing that, adjusting the scores for demographic changes over time. Another approach—which we’ll use here—is to analyze results for each of the three major racial groups, rather than for the overall student population. So let’s take a look at that, first for reading and then for math.

Table 2: Statistically significant changes in reading scale scores, 2011–15

Disaggregating by race reaffirms Indiana’s and Tennessee’s success, as both produced gains in four of the six categories. But it also identifies some additional states worthy of praise for making gains across several categories in reading, including Alaska, Arizona, California, D.C., Hawaii, Iowa, North Carolina, Oregon, Utah, and West Virginia.

Now let’s look at math.

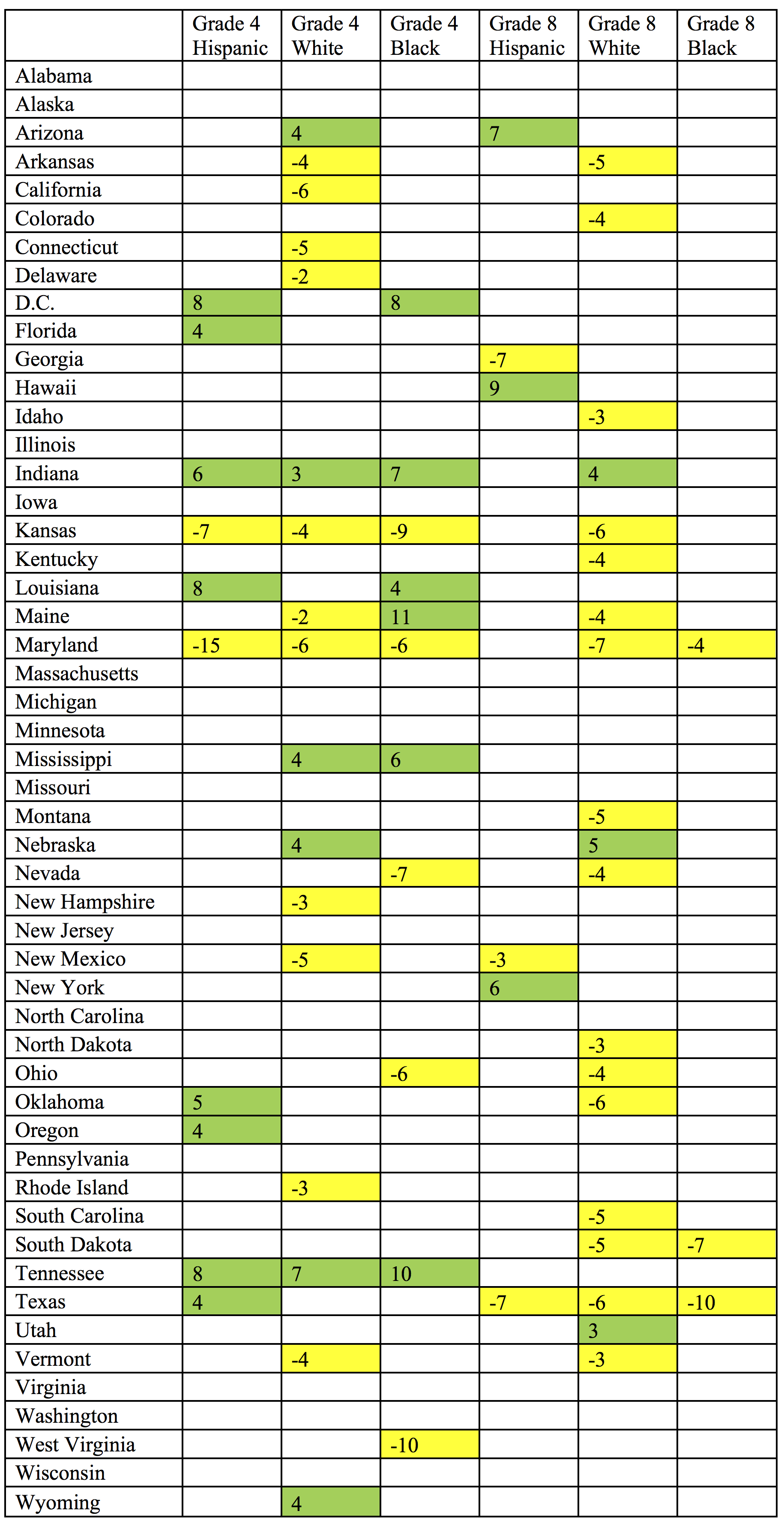

Table 3: Statistically significant changes in math scale scores, 2011–15

As we saw for states overall, there’s less good news in math than in reading, but D.C., Indiana, Tennessee, Nebraska, Louisiana, and Mississippi—all flagged above for producing good progress for all students—deserve praise for improved subgroup performance. Arizona also looks good when viewed in this manner. On the other hand, Texas should worry about its across-the-board declines in 8th grade math. And what’s the matter with Kansas?

As we saw for states overall, there’s less good news in math than in reading, but D.C., Indiana, Tennessee, Nebraska, Louisiana, and Mississippi—all flagged above for producing good progress for all students—deserve praise for improved subgroup performance. Arizona also looks good when viewed in this manner. On the other hand, Texas should worry about its across-the-board declines in 8th grade math. And what’s the matter with Kansas?

***

What to make of all this? The District of Columbia, Indiana, and Tennessee clearly have momentum going into the 2017 NAEP release, with the broadest gains in both subjects and grade levels. All three have been reform hot spots, making them all the more interesting. (Though no, we can’t prove that their reforms—much less which of their reforms—get the credit.)

The District of Columbia has of course been in the news of late for scandals that have taken the shine off the Michelle Rhee/Kaya Henderson apple. Everyone will be watching to see what the NAEP scores show, and what that means for the debate about whether the progress in DCPS is real. (Keep in mind that the data above are for all students in public and charter schools.)

Louisiana and Mississippi are both showing some promise, which is praiseworthy given how far they still have to go. We should keep our eyes on a few other “sleepers”: Iowa, Nebraska, Oregon, and Utah. And are we seeing a resurgence from North Carolina? What about California?

If the states are our laboratories of democracy, we should get some great new data from their education policy experimentation on April 10.

CORRECTION: The original version of this article stated that the results reported here were for public, charter, and private schools. That was incorrect; it's only for public and charter schools. Thanks to the Bluegrass Institute's Richard Innes for pointing out the mistake.

Editor's note: This post is a submission to Fordham's 2018 Wonkathon. We asked assorted education policy experts whether our graduation requirements need to change, in light of diploma scandals in D.C., Maryland, and elsewhere. Other entries can be found here.

What standards should students meet to graduate from high school? In the midst of graduation rate scandals and the ever-increasing population of high school graduates requiring remediation in college, it is no wonder that this question is a hot topic. Ensuing discussions typically revolve around things like the appropriate rigor of diploma requirements, high school graduation exams as proof of student achievement, and accountability changes that could be made to prevent schools from gaming the system. Are there tweaks that could be made to the existing system that could address some of the issues we are seeing today with high school graduation rates? Sure. But that only matters if we are convinced that our current system is worth saving, and as evidenced below, we aren’t sure that we have much (any?) data that says that is true (except the record-high national four-year cohort graduation rate, obviously).

So what is the purpose of high school in America? We think most agree that it is to train our students up to be responsible and productive citizens. But how exactly do we measure that? Research over the years has shown the numerous benefits of high school completion, how it improves the likelihood of higher wages and decreases the likelihood of being arrested for a crime, for example. This type of research led to a focus on graduation as the ultimate measurement. It’s as though we believed that something magical happened by simply pushing all students to get across the graduation stage in four years.

In turn, while the national graduation rate has soared to record highs from 2005 to 2015, the value of a high school diploma, as measured by median annual earnings, has taken a significant dip over that same time period. The value of the diploma has decreased, even as more students have crossed the stage. Would we say that 84.1 percent of our students, all those who graduated in 2016, are leaving high school prepared for successful lives? Ask ten people and we bet you won’t get a single “yes.” Therein lies the problem we are faced with today.

Where did we go wrong and how do we fix it? First, it’s important to change how we measure success. If we want high schools to ultimately turn out responsible and productive citizens and we agree that not every graduate in America today fits that criteria, then let’s not use graduation rate as our ultimate measure of success. Let’s instead measure the outcomes we wish to see after high school; things like employment rates, median annual wages, job satisfaction, and postsecondary educational program enrollment and completion rates. Are these metrics as easy to calculate and report out for every school and district as the four-year cohort graduation rate? No. Should that prevent us from doing it? No (but it often does).

Where did we go wrong and how do we fix it? First, it’s important to change how we measure success. If we want high schools to ultimately turn out responsible and productive citizens and we agree that not every graduate in America today fits that criteria, then let’s not use graduation rate as our ultimate measure of success. Let’s instead measure the outcomes we wish to see after high school; things like employment rates, median annual wages, job satisfaction, and postsecondary educational program enrollment and completion rates. Are these metrics as easy to calculate and report out for every school and district as the four-year cohort graduation rate? No. Should that prevent us from doing it? No (but it often does).

With our focus firmly planted on student outcomes after high school, we can now begin to reimagine the experience itself. The solution—personalized learning, the educational buzz word that has every school across the nation attempting to better serve each student’s unique needs and goals. All the while the system in which these schools operate has continued its one-size-fits-all model. The right hand is saying, “Every child is unique, has different strengths and weakness and dreams, and should have ownership and agency over his/her learning,” yet the left hand is simultaneously shouting, “But don’t forget you need to ensure he/she masters every single rigorous standard, passes every standardized test, and graduates college-and-career ready in four years.” It’s time we take the hands and align the left with the right (and no, that isn’t a political joke).

To build a personalized learning model that effectively graduates students prepared to successfully contribute to society, let’s do three things:

Cross-curricular competency-based learning

Across the country at this very minute, there are thousands of students sitting in classes they could have aced on the very first day of school. An even larger population of students are being dragged along to more advanced concepts before they are ready simply because the teacher needs to cover all of the course objects in the allotted amount of days for the semester. Our current system based entirely on the accrual of seat time and credits in individual subject areas is incredibly outdated. Instead, our high school “graduation plan” should be a cross-curricular checklist of knowledge and skills that students should master in order to graduate. Education Reimagined is partnering with schools nationwide to make learner-centered education like this a reality. The beauty of this model is that it not only allows a student to advance at his/her own pace, but it opens up a wide range of pathways by which a student can demonstrate mastery, which leads us to our next recommendation.

Personalized graduation paths

It’s time we truly acknowledge that every student is unique and in turn provide fully personalized graduation paths. Career and technical education (CTE) and college preparation programs should be seen as equals, preparing students for the next step they choose to take. For example, if the graduation checklist requires students to be able to write a research paper, let’s give them an option to fulfill that in any course whether that is advanced English Literature or a welding course. A 2016 CTE study from the Fordham Institute shows many benefits to a quality CTE program, including an increased likelihood that the student will graduate from high school, enroll in a two-year college, and be employed with a higher wage after graduation. Every student should be given control to create a path toward graduation that uses his/her interests and future plans as a foundation upon which to add relevant coursework, internships, and life skills training. Indiana seems to be leading the way in this area with recently-approved Graduation Pathways.

Realignment across the learning continuum

Embracing the above two recommendations means a shift in American high schools as we know them. Knowing that, it is important that our last recommendation be to reimagine learning across the entire preschool to higher education/career continuum. Instead of moving students in primary grades with age cohorts, let’s focus on competency-based mastery. Give students who need extra time the time that they need to gain understanding and allow those who are ready to move on the chance to advance. Instead of labeling a student as a “failure” for not having graduated from high school in four years, set the expectation that students may master all of the competencies required in anywhere from three to seven years. Connect that high school graduation checklist with expectations of colleges, universities, career training programs, and jobs in order to ensure that when students do graduate they are truly prepared to embrace the next step, whatever that is for them.

So with three simple recommendations we have successfully turned the entire high school system on its head. We warned you in the title—we truly meant high school reimagined.

Editor's note: This post is a submission to Fordham's 2018 Wonkathon. We asked assorted education policy experts whether our graduation requirements need to change, in light of diploma scandals in D.C., Maryland, and elsewhere. Other entries can be found here.

The battery of questions in this year’s Wonkathon prompt is a good one, and they are all deserving of consideration. But I think it overlooks a major consideration: Why four years?

The definition of high school graduation that includes the qualifier “within four years” is now rarely even explicitly expressed, and yet it represents a perverse disincentive in the current system.

Consider this story from early in my own career. I met Pat (not the person’s actual name, of course) in Pat’s freshman year. Pat was taking low-level courses to avoid challenges that were well within Pat’s capabilities, but for a variety of reasons, school wasn’t really Pat’s thing. Pat stumbled through freshman year, and then completely bombed sophomore year and had to repeat most of those courses. Pat turned up in my eleventh grade classroom—now taking higher level, college-bound courses. Pat was a new student. “I was a dope,” Pat told me. “I was wasting my time, but now I’m going to do something with my life.” Pat worked through eleventh grade, continued taking college-prep courses as a senior, graduated, and went on to college, earning a degree in communications.

I would consider Pat one of our great success stories. But it took Pat five years, so to the graduation rate figures, Pat is no different than a student who drops out halfway through high school and never comes back.

Pressure to inflate grades, bogus credit-recovery courses, just plain D.C.-style fraud—these things don’t happen just because school districts are under pressure to graduate students. They happen because districts are under pressure to graduate students Right Now! In Four Years! (The formula has been fiddled with in the last decade, but the four-year deadline remains.)

For all the reform talk these days about personalization and flexibility, policymakers still deny public schools the flexibility to say to a student, “We are going to get you through this. We are going to see you succeed, even if it takes a little bit longer than it does for some of your peers.”

Instead, we have a measuring system that says the instant a student falters or stumbles, there is no benefit to the school in helping that student make it to the finish line a little bit later. A student who has to repeat a year is as bad on paper as a student who walks away and never comes back—but the student who stumbles and stays is far more trouble.

I’ll say without hesitation that the vast majority of schools and teachers work with that stumbling student on the five- (or six-) year plan because it’s the right thing to do, the choice that best fulfills our professional sense of responsibility. But it’s not the choice that our current definition of “graduation rate” rewards. Instead, our current definition rewards getting a diploma in every student’s hand after just four years, no matter what corners must be cut to do so.

Course credits and attendance are more than enough to determine readiness for a diploma. Exit exams, the Big Standardized Test, and credit recovery don’t really add any useful information, and they are all tightly tied to other systems of perverse incentives.

There is no reason for the traditional frame of coursework to be wired to a ticking four-year time-bomb. Removing that four-year deadline would give schools and students some breathing room to get things right instead of worrying about getting it right now.

Editor's note: This post is a submission to Fordham's 2018 Wonkathon. We asked assorted education policy experts whether our graduation requirements need to change, in light of diploma scandals in D.C., Maryland, and elsewhere. Other entries can be found here.

School leaders across the country have systematically lowered graduation standards in order to boost graduation numbers (and their own reputations). So the question at the center of this Wonk-a-thon, “What are appropriate policy responses?” is certainly timely. It is not, however, the core question we should be asking ourselves.

Policy is downstream of politics, politics is downstream of culture, and the culture of the education reform movement has been corrupted. If integrity at the core is not restored, policy “fixes” will merely tinker around the edges of the issue.

The technocratic education reform movement provides structural and social incentives for fraud. The central premise is that by empowering highly-trained central office leaders with world-class systems designed by preeminent experts, we ought to expect “transformative” change. The notion that sitting a bureaucrat trained by the Broad Academy in a chair could fundamentally change the life trajectories of thousands of deeply disadvantaged students within just a couple of years is, to put it mildly, willful wishful thinking. On the other hand, the systems, expectations, and professional incentives provide means and motive to commit fraud. In the rare event that reporters ferret out the fraud, technocratic wonks provide alibis rather than accountability.

Technocrats love to discuss the effects of incentives. For ambitious school administrators, the incentives all align to encourage lowering standards to produce higher statistics to gain applause and promotion. This will not stop until the risks outweigh the rewards. Those responsible for fraud ought not be celebrated as heroes, but instead have their records honestly exposed.

Michelle Rhee claimed on her resume that after two-years of teaching, 90 percent of her students reached the 90th percentile in reading and math. That was not true. John Merrow uncovered documents suggesting that Rhee was “fully aware” of the scope of the cheating scandal under her watch. That stuff didn’t much matter: She still received money from foundations to promote her preferred policies nationwide and was recently considered as a candidate for secretary of education.

Antwan Wilson launched his career by taking the college acceptance rate of Denver’s Montbello High School from 35 to 95 percent. If that sounds familiar, it’s because it was the same stunt that the principal of D.C.’s Ballou High School pulled. All it takes to check the “college acceptance” box is having kids fill out an application to an open-enrollment institution. The paperwork gains were as fictional in Montbello as in Ballou: The year after Wilson left Montbello, 38 percent of seniors actually enrolled in college. Wilson’s resume boasts that as assistant superintendent in Denver, he oversaw “200 percent growth in AP enrollment.” According to state data, AP enrollment went from 5,154 to 7,993. That’s a respectable increase, but nowhere near 200 percent. Wilson’s resume boasts that he pioneered credit-recovery program, leading to higher graduation rates. There was also a major credit-recovery scandal under his watch, prefiguring what was to come.

Despite all this, Chiefs for Change ran a glowing Q&A with Wilson, titled “Education reform is tough. Antwan Wilson may have the answer.” It seems pretty safe to say that he does not. While there’s some poetic justice in seeing a high-flying career start and end with the same stunt, it seems almost unfair that Wilson bore the brunt of the damage for scandals started under his predecessor.

Perhaps the FBI investigation will tell us what Kaya Henderson knew and when she knew it. It wouldn’t be much better if she was truly clueless than if she knew and took credit anyway. We do know that Jason Kamras was tipped off about the discipline scandal. After apparently doing nothing to address it, he is now the superintendent of another major urban district. For her part, Henderson now sits as a superintendent in residence at The Broad Center, is a fellow at the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, and is a distinguished scholar in resident at Georgetown University.

The Washington Post talked to this year’s graduating class; they were deceived and are devastated. They are the victims of feckless leaders, enabled and awarded by the education reform establishment. A movement that started with the mantras “Kids before adults” and “no excuses for failure,” has put school administrators before students and seems content to stay silent in the face of fraud.

Why is it that “accountability”-minded technocratic reforms can’t practice what they preach?

Perhaps it has something to do with the sociological structure of the reform movement, which is largely defined by a series of circular, self-congratulatory confabulations. Reformers create hero narratives and invest their own social capital and status in the status of their supposed heroes. A threat to the reputation of “transformational” leaders is a threat to the reputation of the entire movement. It’s far easier to look the other way and keep doing the same old thing.

Hopefully, technocratic reformers will muster up the courage to call a spade a spade when one stares them straight in the face. If not, then the structural incentive for fraud and inflation will render policy tinkering little more than window dressing.

In the face of these headwinds, only a truly bold policy shift can restore systemic integrity: Make classes optional after tenth grade and grant diplomas to anyone whom a local employer certifies shows up steadily and performs adequately.

In practice, policymakers already view a high school diploma as essentially a signal that a young adult can be employed. Policy should be centered on making sure that students can achieve that outcome, not making sure that adult policymakers can deny this goal to themselves.

This policy shift would also accomplish several salutary outcomes at once.

It would provide not-dishonest means for self-interested superintendents and politicians to post the graduation rate increases they want.

It would free up resources for additional investments in early education (which seems to be a more promising long-term strategy than forcing far-academically-behind seventeen- and eighteen-year-olds to stay sitting in rows of desks).

It would help schools provide better scaffolding and support for students who don’t intend to immediately attend college by freeing up resources for schools to provide those students with practical and professional support.

It would help students from deeply disadvantaged backgrounds provide for their loved ones, and in turn provide the kind of self-respect and confidence that only comes from providing.

It would also alleviate the pressure to “pass and promote,” which systematically undermines the emphasis and quality of schooling far before students near the end of high school.

Would it also have drawbacks? Surely. All policies have tradeoffs. But it seems like a more promising course than deflating the standards of the current system for the benefit of the adults around it at the expense of the students within it.

On this week’s podcast, Jessica Shopoff and Chase Eskelsen, employees of K12, Inc. and winners of Fordham’s 2018 Wonkathon, join Mike Petrilli and Alyssa Schwenk to discuss their ideas for reimagining American high school. On the Research Minute, Amber Northern examines race and gender biases in online higher education.

Rachel Baker et al., “Bias in Online Classes: Evidence from a Field Experiment,” Stanford Center for Education Policy Analysis (March 2018).

In this study, Ian Kingsbury of the University of Arkansas uses data from 394 charter applications in seven states to argue that “stringent regulatory environments impose barriers to aspiring minority candidates and to standalone charter schools.” However, the real story seems to be the disappointing relationship between candidates of color and education and charter management organizations (EMOs and CMOs).

According to Kingsbury, barriers to entering the charter market might manifest in two ways. “First, cumbersome or daunting application processes could deter would-be applicants from applying in the first place…Second, greater regulation could induce authorizers to prefer applications from White applicants and CMO/EMO-affiliated entities.”

Because no data exist for would-be applicants who were deterred, Kingsbury uses the share of applicants affiliated with an EMO or CMO as a proxy for the first form of deterrence. But this is problematic for a number of reasons. (For example, EMOs and CMOs may avoid states that are inhospitable to charters.) Somewhat more plausibly, he uses states’ NACSA scores (which reflect that organization’s opinion of their laws on authorizing) as a proxy for their regulatory environments. But of course, this too can be questioned, as it makes “regulation” unidimensional when in reality it is far more complex.

Regardless, Kingsbury estimates that a one-point increase in a state’s NACSA score is associated with just a 0.4 percentage point increase in an applicant’s odds of management organization affiliation—meaning that moving from the minimum score of zero to the maximum score of thirty-three might increase a state’s management organization affiliation rate by about a dozen percentage points. This is a minor bug if you spend your time worrying about “institutional isomorphism” (or the tendency toward charters that all look and feel the same), but it’s a feature if you buy the research on CMOs’ comparatively strong performance.

More interesting (at least to this reviewer) are the descriptive statistics on applications that the author has compiled. For example, judging from the primary “point-of contact” on charter applications, Hispanics are badly underrepresented among charter applicants in most states; whereas whites are overrepresented in Arizona and Nevada, and African Americans are overrepresented in Indiana, Ohio, and Texas. These imbalances provide necessary context for the second part of the analysis, which looks at approval rates.

Unsurprisingly, applicants affiliated with management organizations are about 20 percentage points more likely to be approved. More troublingly, some fraction of this advantage seems to be driven by race. According to Kingsbury, black and Hispanic candidates are less likely to be affiliated with management organizations. Moreover, affiliated applicants of color are only 10 percentage points more likely to be approved (rather than 20 points). Finally, even after controlling for education and management organization affiliation, candidates of color are still 25 percentage points less likely to be approved. Notably, the racial approval gap swells to 78 percentage points when management organization affiliation is excluded from the model. In other words, most of this gap reflects the relationship between black and Hispanic candidates and management organizations.

To Kingsbury, all of this highlights the folly of overregulation. (For example, a one-point increase in a state’s NACSA score is associated with a 1.7 percentage point decrease in Black and Hispanic applicants’ odds of approval.) However, to this reviewer, the big story is the disappointing relationship between race and management organization affiliation, which raises at least two decidedly awkward questions: Why aren’t management organizations recruiting more African American and Hispanic applicants? And perhaps even more to the point, why don’t the candidates of color they do manage to recruit see more of a boost?

SOURCE: Ian Kingsbury, “Charter School Regulation as a Barrier to Entry,” University of Arkansas (March 2018).

The underrepresentation of high-poverty and minority populations in gifted programs has troubled education analysts and reformers for decades. One finding in this winter’s Fordham report on gifted programming gaps was that although high-poverty schools are as likely as low-poverty schools to have gifted programs, students there are less than half as likely to participate in them. This is complemented by a recent University of Connecticut finding that school poverty has a negative relationship with the percentage of students identified as gifted.

Researchers used student-level data from three state departments of education, supplemented by data from NCES, for the cohort of students who entered third grade in 2011 and completed fifth grade in 2014. The data spanned pupils from 4,546 schools in 367 districts. They used free and reduced-price lunch (FRL) eligibility as a proxy for poverty, and compared FRL eligibility, gifted identification, and performance on reading and math tests at the student, school, and district levels.

Their results confirmed existing knowledge about low rates of identification for low-income students, even after controlling for student performance on standardized tests and school and district demographics. In one state, in an average school and district, a non-FRL student was 3.33 times more likely to be identified than a FRL peer with the same test score. In another, 41 percent of schools had no FRL students identified as gifted.

The researchers also looked between and within districts to find where the greatest variability in the percentage of gifted-identified students lay. They found that the variance in both FRL percentages and gifted identification was far greater between schools within the same district than between different districts. In two of the states, even in schools with comparable achievement on standardized tests, the school with a lower percentage of FRL students tended to identify a higher percentage of students as gifted. (In one state, for example, a 10 percent reduction in FRL students yields a 1.7 percent increase in gifted identification.) And in all three states, FRL percentages at the school level had a negative relationship with gifted identification.

The study does, however, have limitations, such as its broad-brush use of FRL eligibility as a substitute for poverty, its reliance on only one cohort of students across three states, and its inability to account for state and district differences in how they define giftedness and identify students.

Nevertheless, the research further solidifies the known relationship between individual poverty and underidentification for gifted programs, and highlights an additional connection between school-level poverty and underidentification. Schools and districts around the country tend to overlook poor students for these opportunities, and this study demonstrates that inequities within districts are a contributor. Denying low-income kids and kids in low-income schools the benefits of gifted education perpetuates injustice, and we all lose when young people don’t reach their potential.

SOURCE: Rashea Hamilton, et al, “Disentangling the Roles of Individual and Institutional Poverty in the Identification of Gifted Students,” Gifted Child Quarterly (January 2018).