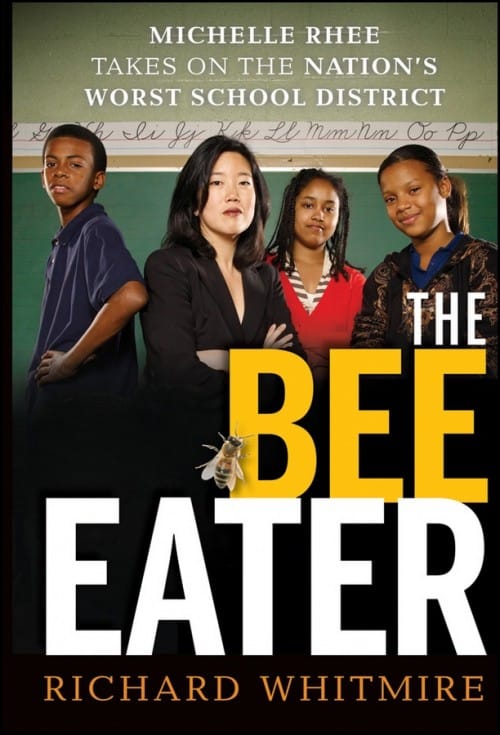

The Bee Eater: Michelle Rhee Takes on the Nation???s Worst School District

A great story with an uncertain ending

A great story with an uncertain ending

This semi-authorized biography of Michelle Rhee

tracks her tenure as an elementary school teacher, her leadership of the

nascent New Teacher Project, and her time as chancellor of D.C.’s public

schools. For those unfamiliar with her formative years, the book provides a

compelling explanation of how she came to be obsessed with teacher quality (and

with firing incompetent employees). And for those who didn’t follow the Washington Post coverage of Rhee’s D.C.

whirlwind, the book offers an inspired narrative. Unfortunately, while Whitmire’s

text is rich in research and peppered with interview quotes, his final

assessment of Rhee’s legacy in D.C. is too vanilla. The five criticisms he does

send her way (e.g. she sometimes had poor media judgment, she fought battles that

did not need to be fought) could have come from any D.C. insider or avid Post reader. Furthermore, he doesn’t

push hard enough on the question of whether Rhee’s reforms actually boosted

student achievement—or are likely to in years to come. Still and all, education

reformers interested in gaining a comprehensive perspective on Michelle Rhee

(the person, not the action figure), or on finding some Waiting for ‘Superman’-like inspiration, would be wise to seek out

and read The Bee Eater.

This semi-authorized biography of Michelle Rhee

tracks her tenure as an elementary school teacher, her leadership of the

nascent New Teacher Project, and her time as chancellor of D.C.’s public

schools. For those unfamiliar with her formative years, the book provides a

compelling explanation of how she came to be obsessed with teacher quality (and

with firing incompetent employees). And for those who didn’t follow the Washington Post coverage of Rhee’s D.C.

whirlwind, the book offers an inspired narrative. Unfortunately, while Whitmire’s

text is rich in research and peppered with interview quotes, his final

assessment of Rhee’s legacy in D.C. is too vanilla. The five criticisms he does

send her way (e.g. she sometimes had poor media judgment, she fought battles that

did not need to be fought) could have come from any D.C. insider or avid Post reader. Furthermore, he doesn’t

push hard enough on the question of whether Rhee’s reforms actually boosted

student achievement—or are likely to in years to come. Still and all, education

reformers interested in gaining a comprehensive perspective on Michelle Rhee

(the person, not the action figure), or on finding some Waiting for ‘Superman’-like inspiration, would be wise to seek out

and read The Bee Eater.

|

Richard Whitmire, The Bee Eater: Michelle Rhee Takes on the Nation’s Worst School District (San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass: A Wiley Imprint, 2011). |

| Click to listen to commentary on the report from the Education Gadfly Show podcast |

Weary of studies that lump

charter schools together and treat them as a monolithic entity? This one,

conducted by top-notch researchers at Harvard’s Center for Education Policy Research and MIT takes a step in the right direction

by parsing effects for urban and nonurban charter schools in Massachusetts. The

report is a follow-up to two earlier evaluations that were limited to schools in Boston

and Lynn. Once again, analysts conduct both a lottery analysis (comparing

students accepted to oversubscribed charters with those who weren’t) and an

expanded observational study (comparing students in middle and high school

charters operating in the Bay State between 2002 and 2009, including the

undersubscribed schools, to those who attended traditional public schools).

Overall, the lottery analysis found that charter middle schools boost average

math scores but have little impact on average English language arts (ELA) scores.

But when the data were disaggregated by school type, researchers found that urban

charter middle schools show significant positive effects on ELA and math

scores. Nonurban middle schools have the opposite impact: zero to negative

effect on a student’s ELA and math state test scores. In fact, while urban

charter schools do especially well with minority and low-income students and

moderately well for white students, nonurban middle schools fail to show gains

for any demographic subgroup, and even post some negative effects for

white students. Delving further, the authors survey school administrators, the

results showing that the successful urban charter schools tend to have longer

days, spend about twice as much time on language and math instruction as

nonurban schools, are more likely to ask parents and

students to sign contracts, and identify with the “no excuses” view on education. The differences in

achievement between the two types of charters, then, should come as little surprise.

Weary of studies that lump

charter schools together and treat them as a monolithic entity? This one,

conducted by top-notch researchers at Harvard’s Center for Education Policy Research and MIT takes a step in the right direction

by parsing effects for urban and nonurban charter schools in Massachusetts. The

report is a follow-up to two earlier evaluations that were limited to schools in Boston

and Lynn. Once again, analysts conduct both a lottery analysis (comparing

students accepted to oversubscribed charters with those who weren’t) and an

expanded observational study (comparing students in middle and high school

charters operating in the Bay State between 2002 and 2009, including the

undersubscribed schools, to those who attended traditional public schools).

Overall, the lottery analysis found that charter middle schools boost average

math scores but have little impact on average English language arts (ELA) scores.

But when the data were disaggregated by school type, researchers found that urban

charter middle schools show significant positive effects on ELA and math

scores. Nonurban middle schools have the opposite impact: zero to negative

effect on a student’s ELA and math state test scores. In fact, while urban

charter schools do especially well with minority and low-income students and

moderately well for white students, nonurban middle schools fail to show gains

for any demographic subgroup, and even post some negative effects for

white students. Delving further, the authors survey school administrators, the

results showing that the successful urban charter schools tend to have longer

days, spend about twice as much time on language and math instruction as

nonurban schools, are more likely to ask parents and

students to sign contracts, and identify with the “no excuses” view on education. The differences in

achievement between the two types of charters, then, should come as little surprise.

Joshua D. Angrist, Sarah R. Cohodes, Susan M. Dynarski, Jon B. Fullerton, Thomas J. Kane, Parag A. Pathak, and Christopher R. Walters, “Student Achievement in Massachusetts’ Charter Schools,” (Cambridge, MA: Center for Education Policy Research at Harvard University, January 2011).

Ronald Wolk, founder and longtime editor of Education Week, and creator of Quality Counts, presents a sobering

message in this new book. As the

title suggests, Wolk outlines why twenty years of American education reform have

yielded no positive changes, hitting hard against standards-based learning, the

fetish with highly-effective teachers, our obsession with testing, and more.

Wolk proposes a second, parallel strategy—one he believes will upend the status

quo and challenge traditional notions of the role and capacity of the education

system. Specifically, he wants more individualized and experiential

instruction, school choice, and alternative teacher preparation. “I find it

hard to imagine that a new strategy would be any riskier or less effective than

the system we have now,” Wolk writes. “Why should new ideas bear the burden of

proof when the existing system is allowed to continue essentially unchanged

even though it is largely failing?” Wolk’s

turnabout may not be as dramatic as Diane Ravitch’s, but it’s a significant shift

all the same: from a top-down standards-based reformer to a libertarian

grass-roots choice advocate. Read the book and enjoy the ride.

Ronald Wolk, founder and longtime editor of Education Week, and creator of Quality Counts, presents a sobering

message in this new book. As the

title suggests, Wolk outlines why twenty years of American education reform have

yielded no positive changes, hitting hard against standards-based learning, the

fetish with highly-effective teachers, our obsession with testing, and more.

Wolk proposes a second, parallel strategy—one he believes will upend the status

quo and challenge traditional notions of the role and capacity of the education

system. Specifically, he wants more individualized and experiential

instruction, school choice, and alternative teacher preparation. “I find it

hard to imagine that a new strategy would be any riskier or less effective than

the system we have now,” Wolk writes. “Why should new ideas bear the burden of

proof when the existing system is allowed to continue essentially unchanged

even though it is largely failing?” Wolk’s

turnabout may not be as dramatic as Diane Ravitch’s, but it’s a significant shift

all the same: from a top-down standards-based reformer to a libertarian

grass-roots choice advocate. Read the book and enjoy the ride.

|

Ronald A. Wolk, Wasting Minds: Why Our Education System Is Failing and What We Can Do About It, (Alexandria, VA: ASCD, 2011). |

The Midwest is in turmoil over proposed changes to state laws that deal with collective-bargaining rights and pensions for public-sector employees, including teachers and other school personnel (as well as police officers, state employees, and more). Madison looks like Cairo, Indianapolis like Tunis, and Columbus like Bahrain, with thousands demonstrating, chanting slogans, and pressing their issues. (Fortunately, nobody has opened fire or dropped “small bombs” as in Tripoli.) Economics are driving this angst: How should these states deal with their wretched fiscal conditions and how should the pain be distributed?

To address these problems, Republican lawmakers and governors have proposed major changes to collective-bargaining laws and pension systems. In Ohio, Senate Bill 5 would continue to afford teachers the right to bargain collectively over wages, hours, and other conditions of employment. But the bill would also make profound alterations to the status quo, including: requiring all public-school employees to contribute at least 20 percent of the premiums for their health-insurance plan; removing from collective bargaining—and entrusting to management—such issues as class size and personnel placement; prohibiting continuing contracts and effectively abolishing tenure; removing seniority as the sole determinant for layoffs and requiring that teacher performance be the primary factor; and abolishing automatic step increases in salary.

Not surprisingly, these changes are being fiercely resisted by the Buckeye State’s teachers, their unions, and their political allies. Battle lines are forming, and we at Fordham—as veteran advocates for “smart cuts” and “stretching the school dollar”—have been drawn into the fray. In the past week, I testified at a legislative hearing on key education components of SB5, and joined a conversation in Dayton with Senator Peggy Lehner and a group of teachers and union leaders. On both occasions, large crowds of disgruntled protestors stood outside the meeting rooms, though most were respectful.

Photo by Eric Albrecht, Columbus Dispatch

In those sessions and beyond, my colleagues and I have argued that changing state law to offer school districts more flexibility over personnel during times of funding cuts is critical for helping them maintain their academic performance. Further, this flexibility to make smart cuts is critical if our schools and students are to emerge out of this financial crisis stronger than ever.

And a crisis it is. The federal “bail-out” dollars that have cushioned Ohio and its school districts for the past two years will dry up by late 2011 and the state is required to balance its budget. Adding to the challenge, dollars for schools must compete with other valuable public programs. Though Ohio’s K-12 enrollment has been all but flat for a decade, during that same period the number of Ohioans enrolled in Medicaid has leaped from 1.3 million to 2.1 million.

Something has to give. The state can either raise taxes or cut programs (or both), but Governor Kasich and the legislative majorities in both chambers were elected in November on the promise not to raise taxes. So cuts will be made and, as K-12 education eats up about 40 percent of the state’s revenue, schools and school employees will bear a share of the pain.

Can this be done while protecting children and their learning? We know, for example, that relying on seniority-based layoffs to close fiscal gaps hurts pupil achievement. Last hired, first fired also hurts high-poverty schools, which typically have more junior teachers. Seniority-based reductions in force (RIF) will also trash some of the state’s most innovative schools—like STEM schools—because they’re new and staffed largely by younger teachers.

I made this case to the group of teachers in Dayton the other morning and they unanimously rejected it. They defended seniority on two fronts. First, they insist that district officials will axe their most expensive teachers first simply to save money. Second, they said, Ohio doesn’t have a decent system for measuring teacher performance, and test scores—they insisted—don’t prove much, and certainly not the caliber of a teacher’s effectiveness.

Further, they kept asking, why the rush? Why all of the sudden is the state needing to make these changes? The teachers felt that GOP lawmakers are attacking them in retaliation for their unions’ lack of support for Kasich in the last election. They seemed completely unaware of how thoroughly they (and other Buckeyes) had been left in the dark these past few years about Ohio’s impending budget cliff—thanks to the federal stimulus dollars, some tricky accounting at the state level, and former Governor Strickland’s celebration of his hocus-pocus school-funding scheme, which promised billions of non-existent new dollars for schools over the next decade.

Earlier this week, the self-same former governor emailed his supporters that “thousands and thousands of Ohioans just like you have crowded the Statehouse because the livelihoods of Ohio’s families are on the line. I was so inspired by these crowds that I decided to join them this past Thursday. There’s just too much at stake to let Governor Kasich and the legislature roll back the clock on progress for Ohio’s middle class.” It’s important to recall that not once during the three gubernatorial debates last autumn did Ted Strickland state that to balance Ohio’s budget he would call for increased taxes. If that wasn’t his intent, however, how did he expect to balance the budget other than by cutting—which is precisely what Republicans are proposing?

Teachers may be forgiven for feeling like all of this change has come out of nowhere because Ohio had zero leadership around the looming fiscal crisis before last month. The real debate in Ohio is just starting and there is no doubt that the current bills under consideration will be significantly amended or even put aside for alternatives. An air of suspense blankets the state until Kasich himself presents his budget by March 15.

Hinting at what’s coming, the other evening he said, “We are searching for a balance. Give our managers, our cities, our schools, and even our state the tools to control their costs.” He added, “Workers have been overpromised. This is not about attacking anybody. It is about fixing the state and making us competitive again.”

He’s right. And it isn’t just Ohio that he’s right about.

|

|

Click to listen to Mike interview Rick Hess on this topic |

Adoption of the Common Core standards comes with a slew of benefits for states—including the high-quality standards themselves, as well as the economies of scale that might come from collaborating with other states on tests, curricula, and more. But as the two federally funded assessment consortia go about their work and flesh out their plans to develop tests aligned to the Common Core, danger lurks. One big challenge arises from their enthusiasm for “through-course assessments”—interim tests that students would take three or four times a year in lieu of a single end-of-year summative assessment. Frequent testing for “formative” purposes is not a new idea and, when limited to diagnostic uses, can be a welcome tool in a teachers’ toolbox. But the intent of the PARCC consortium is for these quarterly tests to count; the results would roll into a summative judgment of whether students—and their schools—are on track. That makes some sense from a psychometric perspective—the assessments can be more closely aligned to what students are actually learning in the classroom, and won’t be subject to the all-or-nothing measurement errors that can stem from once-a-year testing. But there’s a huge downside, as Rick Hess pointed out on his blog last week: It creates powerful incentives for schools to align their own curricula and “scope and sequence” to the quarterly tests, severely undermining school-level autonomy. Building the tests this way is a far more potent “homogenizer” than, say, the kind of “common” curricular materials that the AFT and many other educators are calling for. Such materials would remain voluntary for districts and schools. But once a state adopts a new testing regimen that compels instructional uniformity, only private schools will be able to avoid it. This is particularly problematic for public schools—like charters—that were designed to be different. We still favor the Common Core effort and the trade-off of results-based accountability in return for operational freedom. (We also favor the development of high-quality curricular materials that help teachers handle the Common Core.) But it’s time to ask whether the move to high-stakes interim assessments will make that trade-off untenable.

“Common Core vs. Charter Schooling?!!,” by Rick Hess, Straight Up! Blog, February 18, 2011.

| Click to listen to commentary on Detroit's budget balancing from the Education Gadfly Show podcast |

The Detroit Federation of Teachers has once again proven: It would rather sink the DPS ship than head alee into unfriendly waters. Most recently in Motown, the state superintendent approved a plan from emergency financial manager Robert Bobb to close roughly half of the district’s schools and increase high school class sizes to an unwieldy sixty students. Bobb may have originally proposed the plan, which he himself calls ill-advised, as a strong-arm tactic to force the otherwise recalcitrant union into opening the black boxes of teachers’ benefits and pension packages. Yet the union stranglehold on the district remains intact. By refusing to rethink salaries and pensions, DFT may be defending its members, but its shortsightedness is surely pushing the Motor City toward bankruptcy. Sadly, this predicament is unsurprising—Detroit finished dead last in our 2010 report on the best and worst cities for school reform.

“Detroit Schools’ Cuts Plan Approved,” by Matthew Dolan, Wall Street Journal, February 22, 2011.

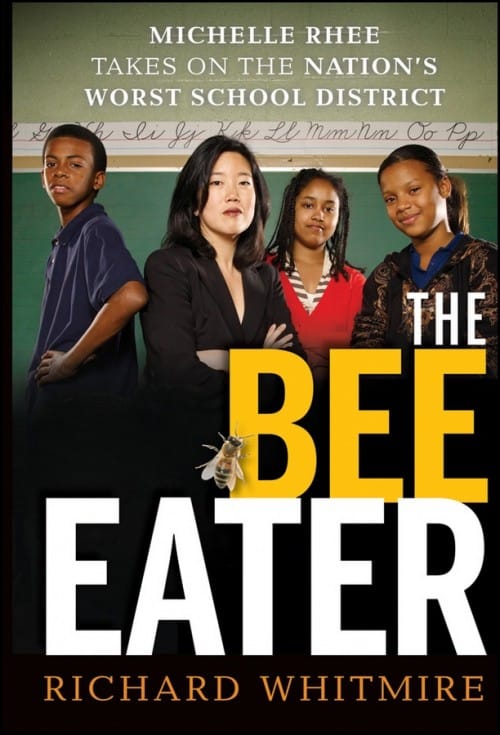

This semi-authorized biography of Michelle Rhee

tracks her tenure as an elementary school teacher, her leadership of the

nascent New Teacher Project, and her time as chancellor of D.C.’s public

schools. For those unfamiliar with her formative years, the book provides a

compelling explanation of how she came to be obsessed with teacher quality (and

with firing incompetent employees). And for those who didn’t follow the Washington Post coverage of Rhee’s D.C.

whirlwind, the book offers an inspired narrative. Unfortunately, while Whitmire’s

text is rich in research and peppered with interview quotes, his final

assessment of Rhee’s legacy in D.C. is too vanilla. The five criticisms he does

send her way (e.g. she sometimes had poor media judgment, she fought battles that

did not need to be fought) could have come from any D.C. insider or avid Post reader. Furthermore, he doesn’t

push hard enough on the question of whether Rhee’s reforms actually boosted

student achievement—or are likely to in years to come. Still and all, education

reformers interested in gaining a comprehensive perspective on Michelle Rhee

(the person, not the action figure), or on finding some Waiting for ‘Superman’-like inspiration, would be wise to seek out

and read The Bee Eater.

This semi-authorized biography of Michelle Rhee

tracks her tenure as an elementary school teacher, her leadership of the

nascent New Teacher Project, and her time as chancellor of D.C.’s public

schools. For those unfamiliar with her formative years, the book provides a

compelling explanation of how she came to be obsessed with teacher quality (and

with firing incompetent employees). And for those who didn’t follow the Washington Post coverage of Rhee’s D.C.

whirlwind, the book offers an inspired narrative. Unfortunately, while Whitmire’s

text is rich in research and peppered with interview quotes, his final

assessment of Rhee’s legacy in D.C. is too vanilla. The five criticisms he does

send her way (e.g. she sometimes had poor media judgment, she fought battles that

did not need to be fought) could have come from any D.C. insider or avid Post reader. Furthermore, he doesn’t

push hard enough on the question of whether Rhee’s reforms actually boosted

student achievement—or are likely to in years to come. Still and all, education

reformers interested in gaining a comprehensive perspective on Michelle Rhee

(the person, not the action figure), or on finding some Waiting for ‘Superman’-like inspiration, would be wise to seek out

and read The Bee Eater.

|

Richard Whitmire, The Bee Eater: Michelle Rhee Takes on the Nation’s Worst School District (San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass: A Wiley Imprint, 2011). |

| Click to listen to commentary on the report from the Education Gadfly Show podcast |

Weary of studies that lump

charter schools together and treat them as a monolithic entity? This one,

conducted by top-notch researchers at Harvard’s Center for Education Policy Research and MIT takes a step in the right direction

by parsing effects for urban and nonurban charter schools in Massachusetts. The

report is a follow-up to two earlier evaluations that were limited to schools in Boston

and Lynn. Once again, analysts conduct both a lottery analysis (comparing

students accepted to oversubscribed charters with those who weren’t) and an

expanded observational study (comparing students in middle and high school

charters operating in the Bay State between 2002 and 2009, including the

undersubscribed schools, to those who attended traditional public schools).

Overall, the lottery analysis found that charter middle schools boost average

math scores but have little impact on average English language arts (ELA) scores.

But when the data were disaggregated by school type, researchers found that urban

charter middle schools show significant positive effects on ELA and math

scores. Nonurban middle schools have the opposite impact: zero to negative

effect on a student’s ELA and math state test scores. In fact, while urban

charter schools do especially well with minority and low-income students and

moderately well for white students, nonurban middle schools fail to show gains

for any demographic subgroup, and even post some negative effects for

white students. Delving further, the authors survey school administrators, the

results showing that the successful urban charter schools tend to have longer

days, spend about twice as much time on language and math instruction as

nonurban schools, are more likely to ask parents and

students to sign contracts, and identify with the “no excuses” view on education. The differences in

achievement between the two types of charters, then, should come as little surprise.

Weary of studies that lump

charter schools together and treat them as a monolithic entity? This one,

conducted by top-notch researchers at Harvard’s Center for Education Policy Research and MIT takes a step in the right direction

by parsing effects for urban and nonurban charter schools in Massachusetts. The

report is a follow-up to two earlier evaluations that were limited to schools in Boston

and Lynn. Once again, analysts conduct both a lottery analysis (comparing

students accepted to oversubscribed charters with those who weren’t) and an

expanded observational study (comparing students in middle and high school

charters operating in the Bay State between 2002 and 2009, including the

undersubscribed schools, to those who attended traditional public schools).

Overall, the lottery analysis found that charter middle schools boost average

math scores but have little impact on average English language arts (ELA) scores.

But when the data were disaggregated by school type, researchers found that urban

charter middle schools show significant positive effects on ELA and math

scores. Nonurban middle schools have the opposite impact: zero to negative

effect on a student’s ELA and math state test scores. In fact, while urban

charter schools do especially well with minority and low-income students and

moderately well for white students, nonurban middle schools fail to show gains

for any demographic subgroup, and even post some negative effects for

white students. Delving further, the authors survey school administrators, the

results showing that the successful urban charter schools tend to have longer

days, spend about twice as much time on language and math instruction as

nonurban schools, are more likely to ask parents and

students to sign contracts, and identify with the “no excuses” view on education. The differences in

achievement between the two types of charters, then, should come as little surprise.

Joshua D. Angrist, Sarah R. Cohodes, Susan M. Dynarski, Jon B. Fullerton, Thomas J. Kane, Parag A. Pathak, and Christopher R. Walters, “Student Achievement in Massachusetts’ Charter Schools,” (Cambridge, MA: Center for Education Policy Research at Harvard University, January 2011).

Ronald Wolk, founder and longtime editor of Education Week, and creator of Quality Counts, presents a sobering

message in this new book. As the

title suggests, Wolk outlines why twenty years of American education reform have

yielded no positive changes, hitting hard against standards-based learning, the

fetish with highly-effective teachers, our obsession with testing, and more.

Wolk proposes a second, parallel strategy—one he believes will upend the status

quo and challenge traditional notions of the role and capacity of the education

system. Specifically, he wants more individualized and experiential

instruction, school choice, and alternative teacher preparation. “I find it

hard to imagine that a new strategy would be any riskier or less effective than

the system we have now,” Wolk writes. “Why should new ideas bear the burden of

proof when the existing system is allowed to continue essentially unchanged

even though it is largely failing?” Wolk’s

turnabout may not be as dramatic as Diane Ravitch’s, but it’s a significant shift

all the same: from a top-down standards-based reformer to a libertarian

grass-roots choice advocate. Read the book and enjoy the ride.

Ronald Wolk, founder and longtime editor of Education Week, and creator of Quality Counts, presents a sobering

message in this new book. As the

title suggests, Wolk outlines why twenty years of American education reform have

yielded no positive changes, hitting hard against standards-based learning, the

fetish with highly-effective teachers, our obsession with testing, and more.

Wolk proposes a second, parallel strategy—one he believes will upend the status

quo and challenge traditional notions of the role and capacity of the education

system. Specifically, he wants more individualized and experiential

instruction, school choice, and alternative teacher preparation. “I find it

hard to imagine that a new strategy would be any riskier or less effective than

the system we have now,” Wolk writes. “Why should new ideas bear the burden of

proof when the existing system is allowed to continue essentially unchanged

even though it is largely failing?” Wolk’s

turnabout may not be as dramatic as Diane Ravitch’s, but it’s a significant shift

all the same: from a top-down standards-based reformer to a libertarian

grass-roots choice advocate. Read the book and enjoy the ride.

|

Ronald A. Wolk, Wasting Minds: Why Our Education System Is Failing and What We Can Do About It, (Alexandria, VA: ASCD, 2011). |