Heterogeneous Competitive Effects of Charter Schools in Milwaukee

Competitive effects need real competition. Go figure!

Competitive effects need real competition. Go figure!

A few studies in the early-to-mid aughts examined the impact of charters on district schools. Most found that the introduction of charter competition led to few changes in district behavior. Others disagreed. This new one by Hiren Nisar (of Abt Associates) re-examines that line of inquiry—but with a twist: Using Milwaukee data, Nisar asks whether district-run charters have more or less impact on the academic performance of traditional public-school students than charters run by other authorizers. (In Milwaukee, this means the city or the local state university.) His study—which attempts to control for student self-selection and ability, school-level factors, and other choice programs (i.e., Milwaukee’s long-running voucher program)—includes roughly forty charters (twenty-three sponsored by MPS and seventeen by others) and utilizes longitudinal, student-level achievement data (for grades three through eight) from 2000-01 to 2008-09. Now to the findings: First, non-district-sponsored charter schools have significant positive impacts on district students’ math and reading achievement, but only in math is that effect statistically different from the impact of district-sponsored charters. This is common-sensical enough. Since district-sponsored schools are still part of the district, with funding that remains within district boundaries, these entities likely feel less of a threat from charter competition. Second, the impact of non-district authorized charters is more pronounced for low achievers and black students, (a finding that reiterates previous research). Nisar’s work provides needed nuance to the body of research on charter competition. But we need to move beyond examination of student outcomes to other interesting questions, such as, under which conditions is charter competition apt to improve both sectors?

Source: Hiren Nisar, Heterogeneous Competitive Effects of Charter Schools in Milwaukee (New York, NY: National Center for the Study of Privatization in Education, March 2012).

Over the past few years, much has been made of students’ “time in learning” (both more time on task while in class and more time in school each day or more days in school each year). Yet little attention has been paid to chronic absenteeism—missing more than 10 percent of a year’s school days—mainly because few states track these data. (Instead, they report average daily attendance, which can mask high levels of chronic absenteeism.) This exploratory study parses attendance data from six states (FL, GA, MD, NE, OR, and RI) and finds chronic absenteeism averaging 14 percent of students. (If this rate holds nationally, the U.S. has lots more students chronically absent—about seven million—than attend charter schools.) The report offers further data, bleak but not altogether surprising: Low-income students are most likely to miss a lot of school, as are the youngest and oldest students. High-poverty urban areas see up to a third of their students miss 10 percent of their courses each year (though the problem is seen in rural poor locations as well). But neither gender nor ethnicity appears to play a role in chronic absenteeism. Policymakers thinking through extended school days and years would be prudent to internalize this study’s message. More learning time will only be productive if the students are in class to take advantage of it.

Over the past few years, much has been made of students’ “time in learning” (both more time on task while in class and more time in school each day or more days in school each year). Yet little attention has been paid to chronic absenteeism—missing more than 10 percent of a year’s school days—mainly because few states track these data. (Instead, they report average daily attendance, which can mask high levels of chronic absenteeism.) This exploratory study parses attendance data from six states (FL, GA, MD, NE, OR, and RI) and finds chronic absenteeism averaging 14 percent of students. (If this rate holds nationally, the U.S. has lots more students chronically absent—about seven million—than attend charter schools.) The report offers further data, bleak but not altogether surprising: Low-income students are most likely to miss a lot of school, as are the youngest and oldest students. High-poverty urban areas see up to a third of their students miss 10 percent of their courses each year (though the problem is seen in rural poor locations as well). But neither gender nor ethnicity appears to play a role in chronic absenteeism. Policymakers thinking through extended school days and years would be prudent to internalize this study’s message. More learning time will only be productive if the students are in class to take advantage of it.

Robert Balfantz and Vaughn Byrnes, The Importance of Being in School: A Report on Absenteeism in the Nation’s Public Schools (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University, May 2012).

Reformers frequently point out that charters are underfunded. They also laud charters that post strong student-achievement scores despite their lean budgets. But is this the norm? Do charter schools ipso facto achieve great results with less funding than traditional schools? As spending data—for charters and districts alike—are generally opaque, there is no clear-cut answer. This study from the NEPC (Kevin Wellner’s pro-union shop) dug into financial data of large charter-management organizations (CMOs) in three states and found a mixed bag: A few successful charter networks spend more than district schools, thanks to aggressive fundraising. Notably, KIPP schools in New York City spend about $4,300 more per pupil than nearby district schools. But many other charters spend far less. Those in Ohio, for example, spend less across the board than district schools in the same city. These data will spur conversation, but be wary of the NEPC’s conclusions, including that the “no excuses” charter model may not be worth its cost or that these charters (and their funding streams) bring up “equity concerns” as they create schools that are overfunded compared to their district counterparts. (Never mind that a swath of charters in this study is funded far below district levels.) There’s also much missing from this forensic account. Notably, the lion’s share of charter schools do not belong to large networks like KIPP—and were left out of this report. Analyzing the revenues of these handpicked “favorites of philanthropy” does little to inform the conversation on spending levels of the entire sector. What would have been a useful report is marred by the authors’ own biases, as they reach for a few conclusions that are only loosely justified by the data.

Bruce D. Baker, Ken Libby, and Kathryn Wiley, Spending by the Major Charter Management Organizations: Comparing Charter School and Local Public District Financial Resources in New York, Ohio, and Texas (Boulder, CO: National Education Policy Center, May 2012).

As Old Farmer has his almanac and Britannica his encyclopedia, the National Center for Education Statistics has the Condition of Education. This annual report offers a comprehensive look at trends in American education, reporting longitudinal data on forty-nine discrete indicators, ranging from pre-Kindergarten enrollment to high school extra-curricular participation to post-secondary faculty make-up. Last year’s headlines related to school choice (and the mushrooming charter sector). The latest edition again shows increased public-school choice—but this time on the digital-learning front (or “distance education,” as they say at NCES). In 2009-10, over 1.3 million high schoolers—across 53 percent of districts—enrolled in a distance-ed course. (This up from 0.3 million five years prior.) Much of the report contains simple factoids, but more than a few indicators will help drive policy conversations on topics as diverse as school finance and instruction. For example, total expenditures per student rose 46 percent (in constant dollars) between 1988-89 and 2008-09, with school-debt interest spending seeing the highest percentage increase, followed by capital outlay and then employee benefits—which subsume close to 20 percent of per pupil costs. On other pages, we learn that enrollment in high school math and science courses just about doubled in the last two decades, while the number of high school pupils holding jobs has halved. This review just scratches the surface of the report: There’s much more worthwhile content within its many pages.

Source: National Center for Education Statistics, The Condition of Education 2012 (Washington, D.C.: United States Department of Education, May 2012).

Mike and Education Sector’s John Chubb analyze Mitt Romney’s brand-new education plan and what RTTT will look like for districts. Amber considers whether competition among schools really spurs improvement.

Heterogeneous Competitive Effects of Charter Schools in Milwaukee

Join us for this important, nonpartisan event about digital learning and where it will take education in Ohio -- and the nation -- in the years to come. National and state-based education experts and policymakers will debate and discuss digital learning in the context of the Common Core academic standards initiatives, teacher evaluations and school accountability, governance challenges and opportunities, and school funding and spending.

Much will swiftly be written about Arne Duncan's brand-new Race to the Top competition for school districts (and, interestingly, for charter schools and consortia of schools), and it's premature to say much on the basis of early press accounts. But Alyson Klein's invaluable Ed Week blog flags one fascinating tidbit that suggests a welcome new Education Department focus on the failings of today's school-governance arrangements:

Just to be eligible, districts by the 2014-15 school year will have to promise to implement evaluation systems that take student outcomes into account—not just for teacher and principal performance, but for district superintendents and school boards. That's a big departure from the state-level Race to the Top competitions, which just looked at educators who actually work in schools, not district-level leaders. [Emphasis added]

How very refreshing, even exhilarating, to see the inclusion of superintendents and boards in a results-based accountability system, rather than the customary focus only on schools and their principals and teachers (and sometimes the kids themselves). Will the NSBA and AASA react angrily to this goring of their own members' oxen? Or will they—as they should—welcome this logical and potentially powerful widening of the theory and practice of accountability?

“Rules Proposed for District Race to Top Contest,” Alyson Klein, Politics K-12 blog, May 22, 2012.

It’s hard to get past the New York Times’s animus toward anything “private” or profit-seeking in the realm of K-12 education, particularly when investigative reporter Stephanie Saul applies her own biased and acidic pen to the topic. And Tuesday’s interminable “expose” of state-level tax-credit scholarship programs certainly deepens one’s impression that the writer (and, presumably, her editors) is in love with anything that smacks of “public dollars” or “public schools” and at war with anything that might be seen as diverting even a penny from state coffers into the hands of parents to educate their kids at schools of their choice. Never mind whether the public schools they are exiting are good or bad, nor whether the dollars being spent by those schools are well targeted on high-quality instruction or frittered away on over-generous benefits for underemployed custodians and their retired pals.

Tax-credit scholarship programs must be well designed and monitored or more "exposes" over how dollars are distributed will follow. Photo by Images Money. |

Having gotten that out of the way, it’s also worth learning that while some of these state programs (especially Florida’s) are models of sound policy, efficient administration, and careful targeting of available resources, some others appear to be burdened by dubious practices on the part of schools, donors, elected officials, and maybe parents, too.

First, a brief refresher on what these programs are and how they work. Eight states allow individuals or corporations to take a full or partial credit against their state taxes for contributions they make to nonprofit groups that award private-school scholarships. Some states, like Florida, award scholarships only to low-income students. Others, such as the programs in Arizona and Georgia, place no income restrictions on eligibility. None excludes participation in religious schooling (and, in fact, the majority of scholarship students attend faith-based schools).

Yes, they are cousins of voucher programs but they don’t involve checks written by the state (or district) to private schools, using money that has already entered the public coffers. The money, in fact, never enters the state treasury. Such programs thus skirt some of the statutory and constitutional obstacles that get in the way of vouchers—and in many cases enjoy smoother political sailing as well.

If Ms. Saul is to be believed, however, some of these programs are vulnerable to various forms of misbehavior, including parents getting cash in their pockets, politicians deciding which schools should benefit, even donors getting tax credits while underwriting particular students.

These programs involve credits against state taxes. Hence a state’s tax code determines what is and isn’t kosher. Certainly some of these alleged practices wouldn’t be acceptable to the Internal Revenue Service. (For example, one cannot make a gift to a college or school that is then used to provide tuition relief to one’s own kid. If that were allowed, nobody would pay tuition to Princeton; they’d make gifts instead—and benefit from the tax deduction.)

Even in Ms. Saul’s telling, it’s evident (from the Florida example) that such programs can be meticulously designed, well run, and close to fool proof. But it also appears that some are loosey-goosey and vulnerable to chicanery. Which raises the question of whose job it is to set them right on behalf of the kids, parents, educators, and taxpayers who have every reason to expect that?

The state, of course, should do much of this. It’s a state program and the state equivalent of the IRS should be monitoring its collection and distribution of money. State watchdog agencies, too, should ensure that taxpayers are benefitting, as has happened in Florida. The state education department (or local school system) should be ensuring that the kids who benefit from it are attending bona fide educational institutions that satisfy the applicable requirements for private schools to operate in that jurisdiction. And legislatures should examine the academic impact of these programs, as greater transparency often weeds out schools with shaky credentials and questionable business practices.

But aspects of this go well beyond state government and could well be superior to it. Should the private school “community,” such as it is, be monitoring its own members for their participation in and handling of such aid programs? (What is the Council for American Private Education and its state affiliates for?) How about the accrediting bodies that typically review many aspects of private schools and allow them (if they pass muster) to declare that they are accredited? What about advocacy groups (such as the American Federation for Children) that press for the expansion and replication of such programs and that presumably have an interest in their integrity and reputation? The private foundations (e.g. Friedman, Walton, DeVos) that underwrite such efforts? Why does this sector of school choice have no counterpart to the National Association of Charter School Authorizers (NACSA) to promulgate a code of sound practices and invite membership from organizations that adhere to these?

The more such entities do to ensure sound practices in state-level tax-credit-scholarship programs, the less temptation there will be for government agencies to clamp down on them, with likely adverse effects on legitimate schools and needy pupils.

And the less that hostile publications like the Times and "gotcha" journalists like Ms. Saul will have with which to make mischief.

PS: It’s not just “private” and “profit” that she abhors. Her piece on Tuesday was really a model of take-no-prisoners left-wing journalism! She hit at least five hot buttons: privatization, football, evolution, fundamentalism, and fracking! Somehow she missed climate change, phonics, and traditional family units.

Ed. note: Adam Emerson previously contributed to policy and public affairs initiatives for Step Up For Students, the scholarship organization responsible for administering the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship for low-income students.

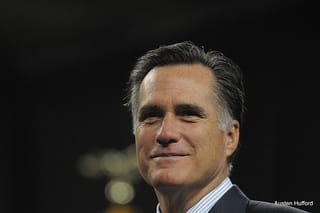

Governor Mitt Romney’s long-awaited education address happened on Wednesday, but the most telling news broke Tuesday, when we learned that Margaret Spellings is no longer one of his education advisors. She quit on principle, I assume, because Romney decided to turn the page on No Child Left Behind. As his campaign’s education “talking points” read, “Governor Romney’s plan reforms [NCLB] by emphasizing transparency and responsibility for results. Rather than federally-mandated school interventions, states would have incentives to create straightforward public report cards that evaluate each school on its contribution to student learning.” (Read his thirty-four-page education policy white paper here.)

Gov. Romney wants to make Title I and IDEA dollars portable—a worthy idea, just make it voluntary. Photo by Austin Hufford |

Today, there’s not a single Republican in the House of Representatives, in the Senate, or running for president willing to defend federal accountability mandates. The GOP conversation has shifted to transparency, in line with what we’ve called Reform Realism. What a difference a decade makes.

The thrust of Romney’s speech, however, wasn’t his fresh view of accountability, but a major proposal on school choice. Romney wants to make Title I and IDEA dollars portable—a form of “backpack funding” from the federal level. (This one’s very much in line with what the Hoover Institution’s K-12 Education Task Force proposed in February. It’s also close kin to what Ronald Reagan and Bill Bennett proposed for Title I back in the late 1980s.) He said:

As President, I will give the parents of every low-income and special needs student the chance to choose where their child goes to school. For the first time in history, federal education funds will be linked to a student, so that parents can send their child to any public or charter school, or to a private school, where permitted. And I will make that choice meaningful by ensuring there are sufficient options to exercise it.

To receive the full complement of federal education dollars, states must provide students with ample school choice. In addition, digital learning options must not be prohibited. And charter schools or similar education choices must be scaled up to meet student demand.

There’s a lot to be said for making federal dollars follow disadvantaged children to their schools of choice:

But it’s not without drawbacks:

The biggest concern comes with having Uncle Sam try to use his ten cents on the education dollar to foist major changes on the states. Photo by Mollie McCabe. |

The biggest concern, though, comes with having Uncle Sam try to use his ten cents on the education dollar to foist major changes on the states. We’ve seen how that works (or doesn’t) in the context of accountability; why do we think it will work better in the context of school choice?

See this passage, in particular, from Romney’s education white paper:

To expand the supply of high-performing schools in and around districts serving low-income and special-needs students, states accepting Title I and IDEA funds will be required to take a series of steps to encourage the development of quality options: First, adopt open-enrollment policies that permit eligible students to attend public schools outside of their school district that have the capacity to serve them. Second, provide access to and appropriate funding levels for digital courses and schools, which are increasingly able to offer materials tailored to the capabilities and progress of each student when used with the careful guidance of effective teachers. And third, ensure that charter school programs can expand to meet demand, receive funding under the same formula that applies to all other publicly-supported schools, and access capital funds.

Note especially the phrase, “will be required.” We’ve been down that road before! And note how far this proposal is from the “let states do whatever they want with their federal dollars” approach of House education-committee chairman John Kline.

A better idea might be to take a page from the Obama administration's handbook and make funding portability voluntary. Give states the option to “voucherize” their Title I and IDEA funds. Make them take the steps above in order to participate in that option. Maybe offer a little extra money on top. And see if you get any takers. That’s a way to promote innovation and choice without falling into the same federalism trap that snared No Child Left Behind. And states that opt into it would very likely make their own dollars portable, too.

This plan is a good start. You’ve got five and a half months till Election Day, Governor Romney, to make it even better.

Faced with the need to cut staff, but prevented by last-in, first-out requirements from axing the lousiest educators, Newark is looking to follow NYC’s lead and pay its way out of the problem by buying out low-performing teachers with its Mark Zuckerberg-donated cash. While Facebook’s flop may limit the plan’s reach, it’s encouraging to see a district so committed to having a quality teaching force that it’s willing to spend to bypass the absurdity of LIFO.

While it may not be Texas, the Common Core gained a new adherent this week when schools serving Department of Defense families announced they adopted the standards. While implementation remains a challenge everywhere, 87,000 students from military families living in a dozen countries, from Germany to Japan, will now be taught to rigorous standards, a development worth saluting.

While it may not be Texas, the Common Core gained a new adherent this week when schools serving Department of Defense families announced they adopted the standards. While implementation remains a challenge everywhere, 87,000 students from military families living in a dozen countries, from Germany to Japan, will now be taught to rigorous standards, a development worth saluting.

Cleveland Mayor Frank Jackson proposed a thoughtful tweak to his school-reform plan this week, shifting the accountability focus from startup charter schools to authorizers. The mayor’s move demonstrated that compromise and progress are possible, a lesson that state lawmakers should learn as the bill remains stalled in the legislature.

Data-driven, data-driven, data-driven. The phrase is inescapable in every aspect of teacher policy—except, it turns out, when it comes to educating educators. A new National Council on Teacher Quality study finds teacher prep programs skimp on training aspiring educators to use student-assessment info, providing this week’s reminder of how backwards America’s ed schools remain.

From tax-credit scholarships to online learning, privatization is a four-letter word in liberal education (and many other) spheres, and George Soros has now bankrolled a website that offers a one-stop shop for everyone convinced that privatization is a nefarious global plot to turn schools over to corporate raiders. For those looking for commentary receptive to a responsible role for markets and free enterprise in education, the Gadfly humbly offers an alternative: www.edexcellence.net.

Join us for this important, nonpartisan event about digital learning and where it will take education in Ohio -- and the nation -- in the years to come. National and state-based education experts and policymakers will debate and discuss digital learning in the context of the Common Core academic standards initiatives, teacher evaluations and school accountability, governance challenges and opportunities, and school funding and spending.

Join us for this important, nonpartisan event about digital learning and where it will take education in Ohio -- and the nation -- in the years to come. National and state-based education experts and policymakers will debate and discuss digital learning in the context of the Common Core academic standards initiatives, teacher evaluations and school accountability, governance challenges and opportunities, and school funding and spending.

A few studies in the early-to-mid aughts examined the impact of charters on district schools. Most found that the introduction of charter competition led to few changes in district behavior. Others disagreed. This new one by Hiren Nisar (of Abt Associates) re-examines that line of inquiry—but with a twist: Using Milwaukee data, Nisar asks whether district-run charters have more or less impact on the academic performance of traditional public-school students than charters run by other authorizers. (In Milwaukee, this means the city or the local state university.) His study—which attempts to control for student self-selection and ability, school-level factors, and other choice programs (i.e., Milwaukee’s long-running voucher program)—includes roughly forty charters (twenty-three sponsored by MPS and seventeen by others) and utilizes longitudinal, student-level achievement data (for grades three through eight) from 2000-01 to 2008-09. Now to the findings: First, non-district-sponsored charter schools have significant positive impacts on district students’ math and reading achievement, but only in math is that effect statistically different from the impact of district-sponsored charters. This is common-sensical enough. Since district-sponsored schools are still part of the district, with funding that remains within district boundaries, these entities likely feel less of a threat from charter competition. Second, the impact of non-district authorized charters is more pronounced for low achievers and black students, (a finding that reiterates previous research). Nisar’s work provides needed nuance to the body of research on charter competition. But we need to move beyond examination of student outcomes to other interesting questions, such as, under which conditions is charter competition apt to improve both sectors?

Source: Hiren Nisar, Heterogeneous Competitive Effects of Charter Schools in Milwaukee (New York, NY: National Center for the Study of Privatization in Education, March 2012).

Over the past few years, much has been made of students’ “time in learning” (both more time on task while in class and more time in school each day or more days in school each year). Yet little attention has been paid to chronic absenteeism—missing more than 10 percent of a year’s school days—mainly because few states track these data. (Instead, they report average daily attendance, which can mask high levels of chronic absenteeism.) This exploratory study parses attendance data from six states (FL, GA, MD, NE, OR, and RI) and finds chronic absenteeism averaging 14 percent of students. (If this rate holds nationally, the U.S. has lots more students chronically absent—about seven million—than attend charter schools.) The report offers further data, bleak but not altogether surprising: Low-income students are most likely to miss a lot of school, as are the youngest and oldest students. High-poverty urban areas see up to a third of their students miss 10 percent of their courses each year (though the problem is seen in rural poor locations as well). But neither gender nor ethnicity appears to play a role in chronic absenteeism. Policymakers thinking through extended school days and years would be prudent to internalize this study’s message. More learning time will only be productive if the students are in class to take advantage of it.

Over the past few years, much has been made of students’ “time in learning” (both more time on task while in class and more time in school each day or more days in school each year). Yet little attention has been paid to chronic absenteeism—missing more than 10 percent of a year’s school days—mainly because few states track these data. (Instead, they report average daily attendance, which can mask high levels of chronic absenteeism.) This exploratory study parses attendance data from six states (FL, GA, MD, NE, OR, and RI) and finds chronic absenteeism averaging 14 percent of students. (If this rate holds nationally, the U.S. has lots more students chronically absent—about seven million—than attend charter schools.) The report offers further data, bleak but not altogether surprising: Low-income students are most likely to miss a lot of school, as are the youngest and oldest students. High-poverty urban areas see up to a third of their students miss 10 percent of their courses each year (though the problem is seen in rural poor locations as well). But neither gender nor ethnicity appears to play a role in chronic absenteeism. Policymakers thinking through extended school days and years would be prudent to internalize this study’s message. More learning time will only be productive if the students are in class to take advantage of it.

Robert Balfantz and Vaughn Byrnes, The Importance of Being in School: A Report on Absenteeism in the Nation’s Public Schools (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University, May 2012).

Reformers frequently point out that charters are underfunded. They also laud charters that post strong student-achievement scores despite their lean budgets. But is this the norm? Do charter schools ipso facto achieve great results with less funding than traditional schools? As spending data—for charters and districts alike—are generally opaque, there is no clear-cut answer. This study from the NEPC (Kevin Wellner’s pro-union shop) dug into financial data of large charter-management organizations (CMOs) in three states and found a mixed bag: A few successful charter networks spend more than district schools, thanks to aggressive fundraising. Notably, KIPP schools in New York City spend about $4,300 more per pupil than nearby district schools. But many other charters spend far less. Those in Ohio, for example, spend less across the board than district schools in the same city. These data will spur conversation, but be wary of the NEPC’s conclusions, including that the “no excuses” charter model may not be worth its cost or that these charters (and their funding streams) bring up “equity concerns” as they create schools that are overfunded compared to their district counterparts. (Never mind that a swath of charters in this study is funded far below district levels.) There’s also much missing from this forensic account. Notably, the lion’s share of charter schools do not belong to large networks like KIPP—and were left out of this report. Analyzing the revenues of these handpicked “favorites of philanthropy” does little to inform the conversation on spending levels of the entire sector. What would have been a useful report is marred by the authors’ own biases, as they reach for a few conclusions that are only loosely justified by the data.

Bruce D. Baker, Ken Libby, and Kathryn Wiley, Spending by the Major Charter Management Organizations: Comparing Charter School and Local Public District Financial Resources in New York, Ohio, and Texas (Boulder, CO: National Education Policy Center, May 2012).

As Old Farmer has his almanac and Britannica his encyclopedia, the National Center for Education Statistics has the Condition of Education. This annual report offers a comprehensive look at trends in American education, reporting longitudinal data on forty-nine discrete indicators, ranging from pre-Kindergarten enrollment to high school extra-curricular participation to post-secondary faculty make-up. Last year’s headlines related to school choice (and the mushrooming charter sector). The latest edition again shows increased public-school choice—but this time on the digital-learning front (or “distance education,” as they say at NCES). In 2009-10, over 1.3 million high schoolers—across 53 percent of districts—enrolled in a distance-ed course. (This up from 0.3 million five years prior.) Much of the report contains simple factoids, but more than a few indicators will help drive policy conversations on topics as diverse as school finance and instruction. For example, total expenditures per student rose 46 percent (in constant dollars) between 1988-89 and 2008-09, with school-debt interest spending seeing the highest percentage increase, followed by capital outlay and then employee benefits—which subsume close to 20 percent of per pupil costs. On other pages, we learn that enrollment in high school math and science courses just about doubled in the last two decades, while the number of high school pupils holding jobs has halved. This review just scratches the surface of the report: There’s much more worthwhile content within its many pages.

Source: National Center for Education Statistics, The Condition of Education 2012 (Washington, D.C.: United States Department of Education, May 2012).