Among the many problems facing American K–12 education, we don’t have enough highly effective, minority, or male teachers.

Two recent reports from the Center for American Progress (CAP) underscore the first and second of these three shortfalls. As for gender, you can take a look at the NCES data—or just take my word that there are more than three female teachers in U.S. public schools for every male teacher.

If you had to choose, would you rather have your child taught by a highly effective teacher or one who shares his or her race and/or gender?

Of course you’d prefer all of the above, but you may have to face the reality that not many families can have it. I’m reminded of the timeworn conundrum presented to impatient, parsimonious, quality-minded customers by any number of prospective vendors and contractors: “Yes, we can do it better, faster, or cheaper—but we cannot do all three at once. Pick no more than two.”

In a perfect world, you might want your child to be taught by someone who “looks like” him or her and is also highly effective in the classroom. But effective teachers of any race are hard to come by. There just aren’t enough of them, especially in schools serving poor kids. And the pay isn’t good enough to lure huge numbers of others away from more lucrative opportunities. For decades now, American public education has invested its ever-growing budgets in more teachers rather better ones. This is in marked contrast to the staffing practices of most countries that surpass our performance on PISA, TIMSS, and kindred measures. They’ve reached for quality rather than quantity—and for the most part, they have larger classes taught by abler and better-educated instructors (yet who also have more time during the day for lesson planning and such).

Any number of policy changes would gradually move us in that direction, too, but the political obstacles are huge and the timeline would inevitably be long.

Meanwhile, CAP analysts (and many others) are obsessing over the distribution of the too-few quality teachers that we already have and, most recently, over the ethnicity of those standing in front of our children’s classrooms. (Far less attention is paid to the gender discrepancy.)

The numbers themselves are not in dispute. As CAP’s Ulrich Boser writes, “Today, students of color make up almost half of the public-school population. But teachers of color are just 18 percent of the teaching profession.”

What is at issue is the severity of this problem and the extent to which policymakers and ed-reformers should focus time, energy, and resources on solving it versus the innumerable other challenges that plague our K–12 system. And finding teachers who are both effective and minority is doubly difficult.

It’s a fact. Not enough minority individuals complete college with a solid undergraduate education—due in no small part to failings of the K–12 system as well as institutional weaknesses at the postsecondary level—and those that do have their pick of an amplitude of good (and well-paid) jobs in myriad fields.

Let’s recognize up front that any solutions to the shortage of quality teachers, especially from minority groups, are bound to be very slow, relatively expensive, and in competition with other acute education needs (e.g., strengthening the knowledge and skill sets of the teachers we already have, giving kids more quality options, making more adroit uses of technology, extending learning time, and getting better leaders into schools).

As for the seriousness of this problem, any such discussion must begin by asking after the exact nature of the issue. If I don’t care whether my child’s teacher is right- or left-handed, tall or short, green-eyed or brown-eyed, or dressed in slacks versus skirts, why do I care about her (or his) race?

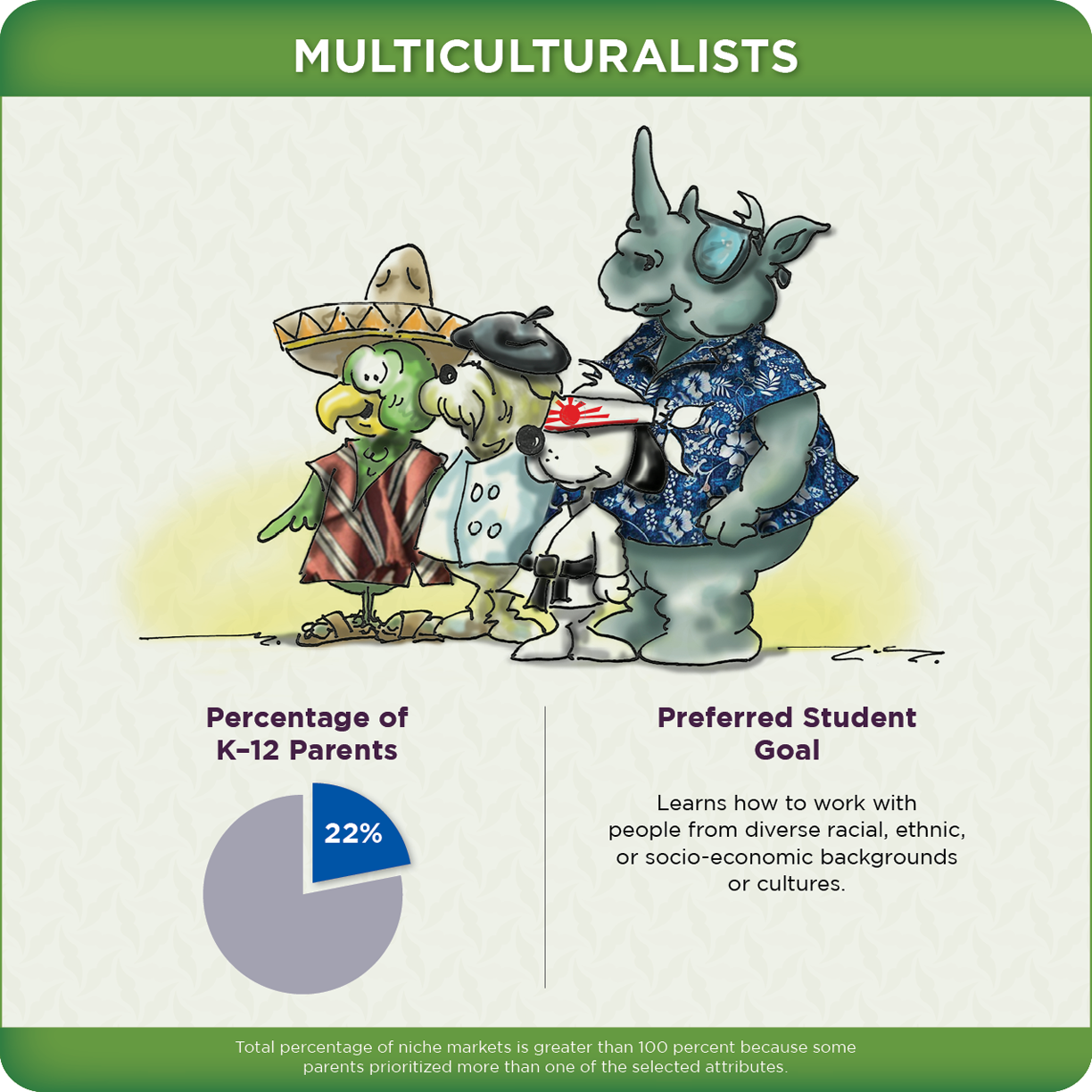

Several answers are possible. Parents may be looking for suitable role models for their child and believe that this is best done by someone who “looks like” their child. They may be strong partisans of ethnic solidarity and want their children to be educated in that sort of environment. They might believe that their child will be better treated by someone of similar background (or they might fear the reverse, that their child will be discriminated against by an instructor with a different background).

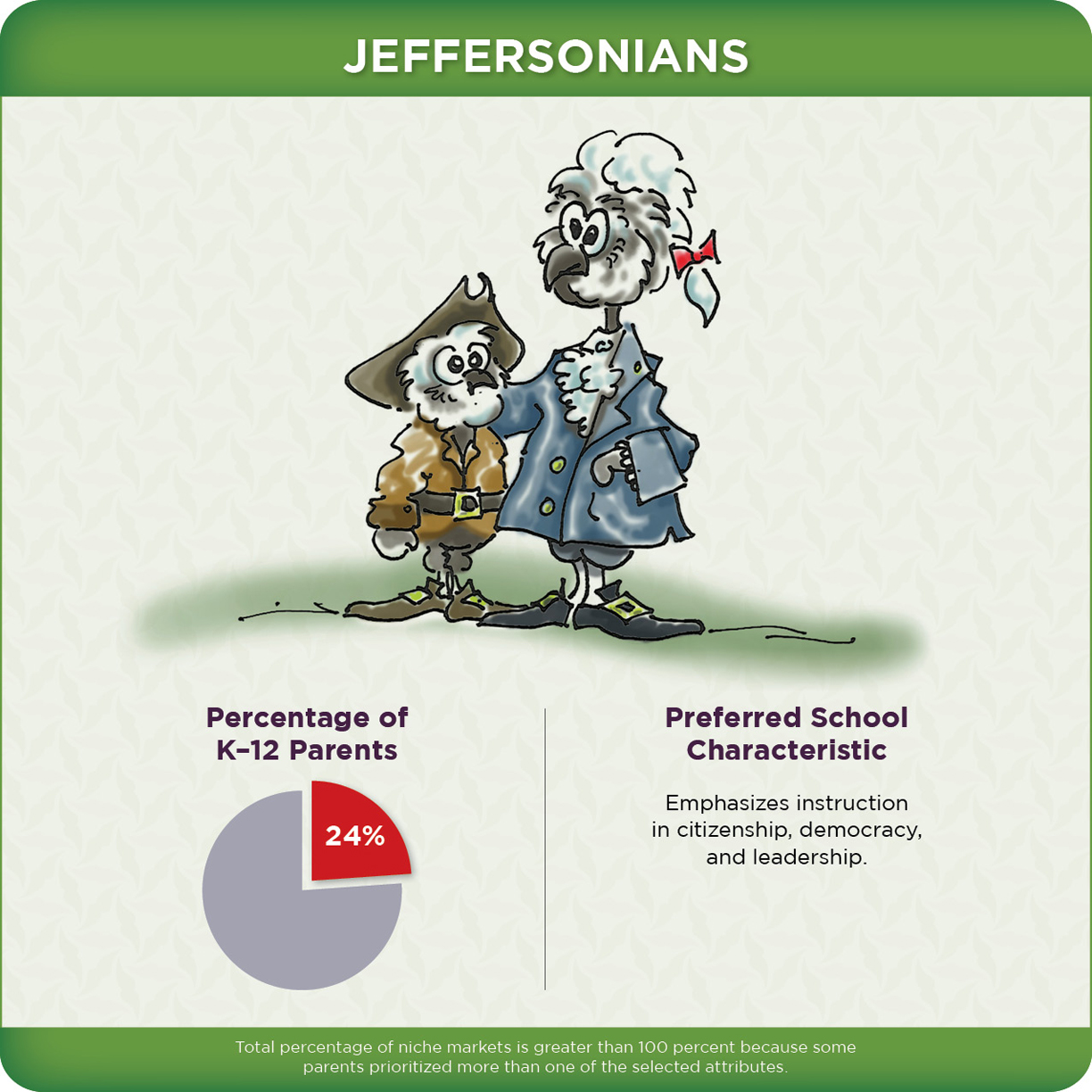

Keep in mind, too, that some parents crave the opposite: forms of unfamiliarity and diversity in children’s schooling experience that will better prepare them for adult success in a multiracial society, where they are apt to spend much their time in the company of people who do not look like them.

That parent (and student) preferences and priorities differ is one of the powerful arguments for school diversity and choice. Whether schools (or individual classrooms) should be organized and staffed primarily according to race is, however, a tricky issue both legally and morally, particularly in the public sector, where such moves can easily turn (or appear) discriminatory and end up violating sundry civil-rights statutes and constitutional prohibitions.

It’s one thing for parents voluntarily to seek out a school—public or private—that is relatively homogeneous, perhaps because it is located in a uniracial neighborhood or has an academic or language focus that is particularly appealing to families of a particular background. But it’s quite another thing for public officials to say, “This is a school for children of Hispanic origin and will be staffed by persons of Hispanic origin.” Shades of Jim Crow and the pre-Brown, pre–Civil Rights Act era!

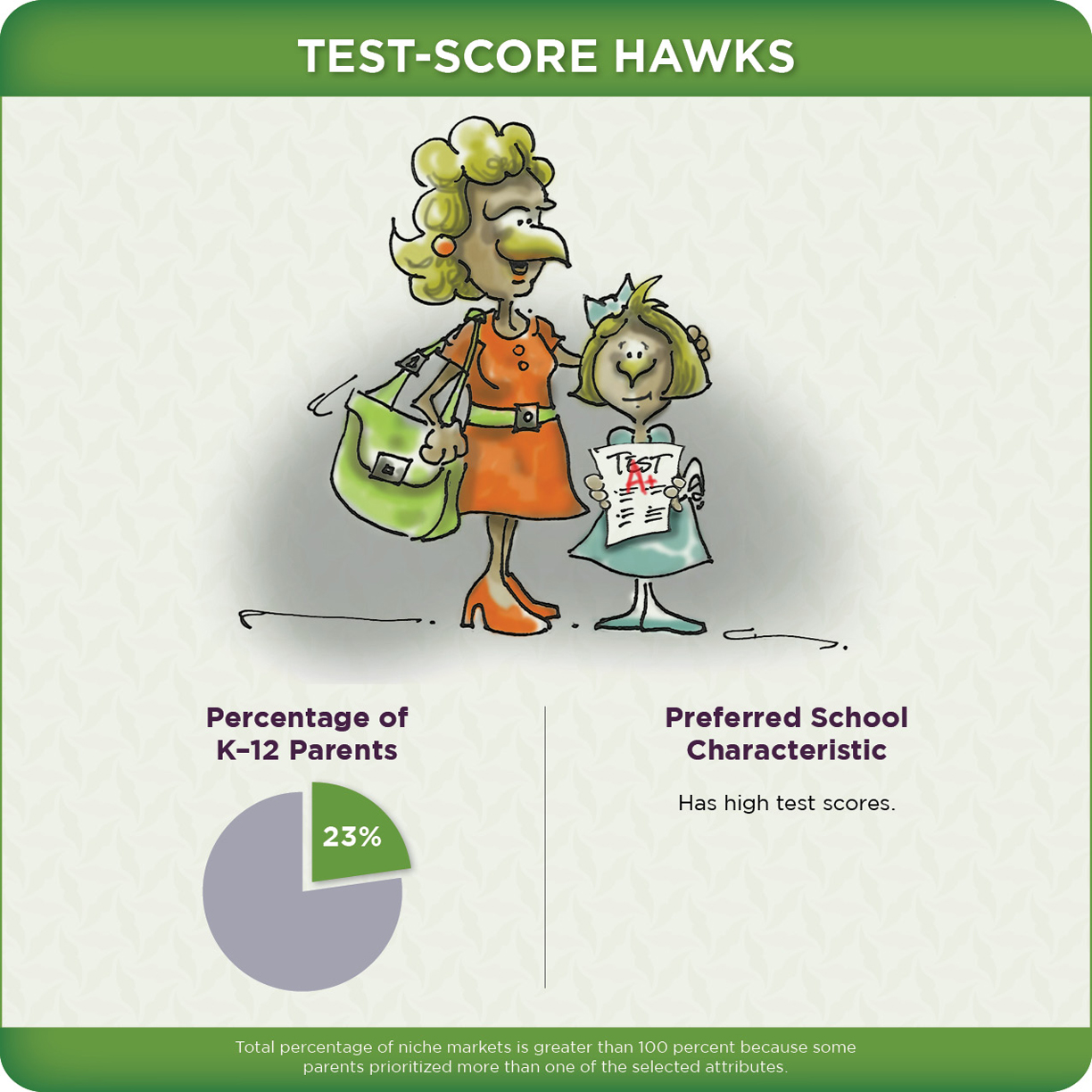

As for academic achievement (which I take to be the foremost goal of U.S. education policy in the twenty-first century), although there’s been a vast amount of assertion that children learn more from teachers who “look like” them and understand their culture, there’s not much robust research undergirding such assertions.

The best of it has been done by Stanford economist Thomas Dee, who did indeed find achievement benefits in the early grades for children taught by teachers of their own race. This was true for both white and black pupils, though for black youngsters the benefits were strongest in disadvantaged and predominantly black schools. (Dee speculated that this might be due to the fact that white teachers found in such schools are apt to be the less-effective kind.)

But Dee’s caveats are also important to consider: the risk of possible harm to pupils in the same classroom who do not share the teacher’s demographics; the heightened risk of resegregation of schools or classrooms, with resulting damage to social relations and civil harmony (not to mention the legal issues that may arise); and the blunt fact that practically nothing is really known “about why the racial match between students and teachers seems to matter.” If that were better understood, he conjectures, we might be able to devise “improvements in training that could make teachers equally effective for all students, regardless of race.”

Which brings us back to the teacher-effectiveness challenge, surely a higher priority than the minority-teacher drought. But while we may be able to imagine rising to that challenge, we can’t begin to imagine how many advocacy groups and analysts such an accomplishment would put out of business, if only because they’d rather deal with hot-button issues like racial balance than with the long, painful slog toward better teachers in every classroom.