Last Tuesday, Ohioans finally voted in primaries for state representative and (if applicable) state senator after the traditional spring primary was delayed due to redistricting issues. As might be expected for a summer election with few competitive races, statewide voter turnout was a dismal 7.9 percent.

In addition to primaries, a handful of districts had tax measures on the ballot. In the Dayton Daily News’s election coverage, it noted two such levy requests in the area, one for Ross and the other for Clark-Shawnee. The Ross tax request lost by a 64-36 percent margin, while Clark-Shawnee’s narrowly passed by eleven (yes eleven) votes. By the looks of it, roughly a quarter of voters in those districts turned out. The Ross school board has already said their proposal will be back on the ballot in November.

Ohio’s summer elections aren’t exactly a shining example of democracy in action. The irregular timing discourages participation and results in a small fraction of voters—likely those with the strongest interest in the outcome—holding undue influence. And no one should expect citizens to be plugged into local politics year-round. In a promising move, legislation passed last December by the House would eliminate August elections, including the ability of districts to put tax measures on the ballot during the dog days of summer.[1] The Senate should take up this cause in the coming months.

Not only is the timing quirky, but the type of levy that Ross and Clark-Shawnee proposed is also unusual. In Ross’s case, the district requested a new “emergency levy” that would have raised the property taxes of its citizens. Clark-Shawnee had the same type of levy on the ballot, but it was asking voters to renew two previously approved emergency levies passed in 2012 and 2014. While voters in that district wouldn’t have experienced a tax hike, their taxes would have been cut had they rejected the proposal.

Despite the alarming terminology, an emergency levy is not as ominous as it sounds. It doesn’t require a district to be in an actual “fiscal emergency,” a formal designation declared by the auditor of state that results in a district being overseen by a state commission. In fact, neither Ross nor Clark-Shawnee is in fiscal emergency; they aren’t even in the less-severe distress categories known as “fiscal watch” or “fiscal caution.” According to the Ohio Department of Taxation, 215 school districts—about one in three—imposed an emergency levy in 2021. Yet only two districts are currently in any of the state’s three categories of fiscal distress.

By state law, all districts have to say is that the dollars are needed “to avoid an operating deficit.” At first blush, the clause doesn’t sound problematic until we realize how much leeway it gives districts. For instance, it doesn’t say anything about the size of the deficit they must be facing. Does a $100 shortfall count? Moreover, districts could “game” their budget projections to create deficits on paper that allow them to propose an emergency levy. Or they could choose not to take reasonable cost-containment measures—creating an “emergency” of their own doing—in the hopes of a taxpayer bailout. Yet by using “emergency” language, districts likely increase the odds that voters will approve a tax hike (as opposed to putting a general-operating levy request before voters asking for additional dollars).

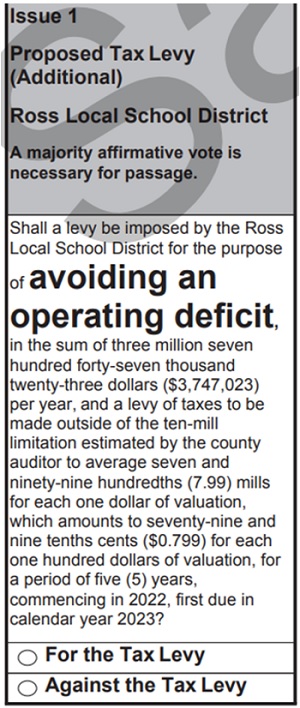

The ballot language for emergency levies is also peculiar. The figure to the right displays Ross’s levy request as presented on voter ballots. What jumps out is the large, boldfaced text “avoiding an operating deficit.” Remember, the ballot language for a normal, general operating or bond levy does not have any bold or large-print font in the question (see here for an example). But state law actually requires the purpose of an emergency levy to be printed in bold and with typeface that is “at least twice the size” of the font around it. As we know from surveys, the wording and presentation of questions can affect the response. What we have here is akin to a loaded question. The language in bold print is likely to lead voters towards a “yes” vote, perhaps out of fear that failing to do so will cause financial ruin for the district (though it could work the other way if people are led into believing a district is mismanaging funds). In the end, the ballot language doesn’t guarantee victory for one side or the other, but it could tip the scales in close races.

In my view, Ohio should eliminate emergency levies altogether. Current emergency levies could be grandfathered or extended, but districts would no longer be able to propose a new one. If districts believe they need more funding, they can always put forward a normal operating tax request before voters without the brazen “emergency” terminology and the outrageous ballot language. Absent elimination, legislators could at least tighten statutory requirements to allow only districts in state-designated fiscal distress categories to put this type of levy on the ballot. They should also consider removing the provision that calls for the large, bold-faced print. The question should be presented neutrally to voters without pushing them in one direction or the other.

Ohio taxpayers deserve to be treated fairly when their local districts request funding. They should have the opportunity to vote on tax rates at conventional times—spring and fall—when decisions about elected offices and other political matters are being made. Taxpayers should also be presented an evenhanded tax request, not one that uses frightening language. With some changes to current statute, state lawmakers would encourage broader participation and present a more neutral question.

[1] The bill allows for an exception if a district is in state-designated “fiscal emergency.”