If you have any friends concerned with gifted education—or educational excellence in general—you saw them doing cartwheels last week, and for good reason: The final Every Student Succeeds Act accountability regulations were released, and language was added allowing for pro-excellence strategies to be used in states’ K–12 accountability systems (some ideas here and here). This is a huge improvement over No Child Left Behind, which incentivized states to design these systems in ways that gave no credit to schools and educators who moved students into advanced levels of achievement. Providing credit to schools that produce advanced learners has been widely suggested as a way to promote excellence in our schools and society at large, so this was unambiguously great news.

But we also received information last week that should temper the enthusiasm and reinforce the urgency for fostering educational excellence.

The 2015 results from the Trends in Math and Science Study (TIMSS) were released, and as one of the two major international, comparative assessments, the findings are eagerly anticipated every four years. TIMSS always tests grades 4 and 8, and this year they tested high school students in advanced math and science (which they last did in 2008; not every country participates due to conflicts with national college entrance exams). These high-quality assessments are administered under the auspices of the IEA, which is led by a sharp bunch of psychometricians, educators, and policy experts. IEA produces solid data, and my colleagues and I follow their testing programs closely.

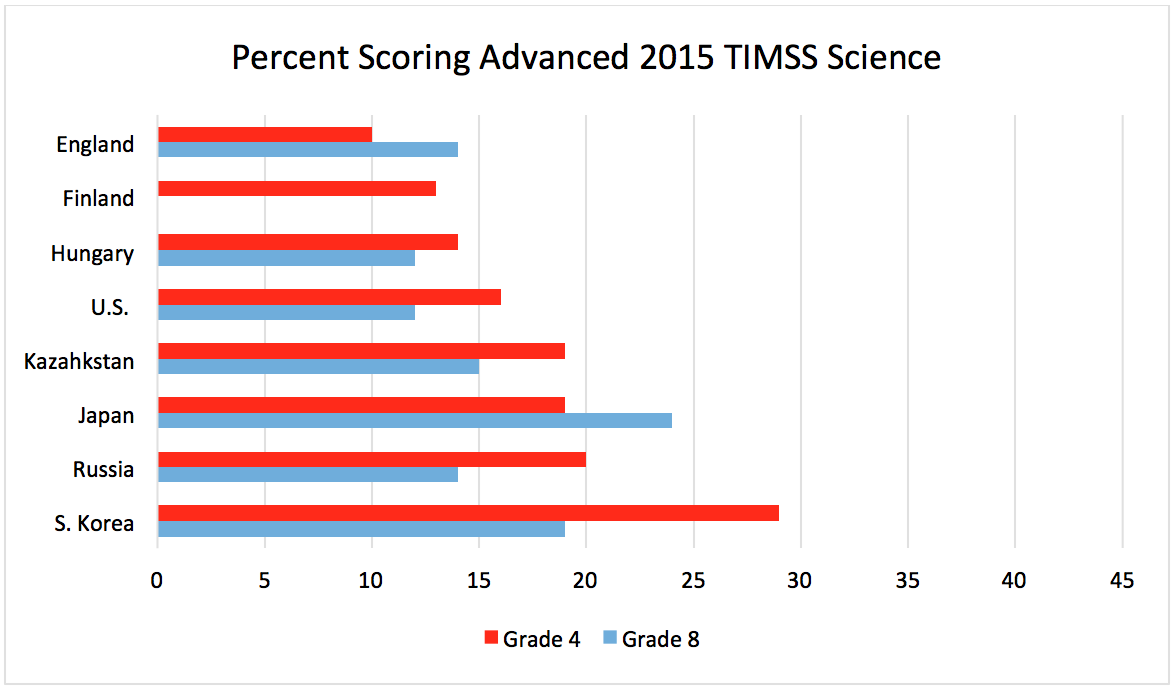

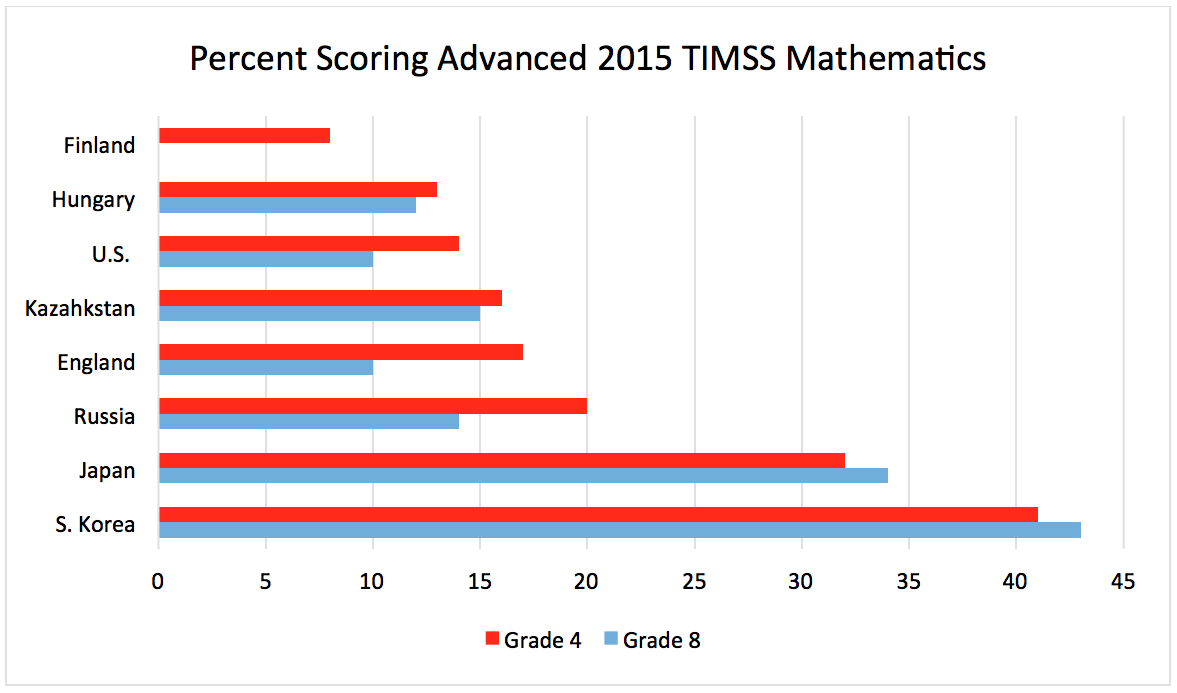

There’s no way to sugarcoat the results: The U.S. produces a much smaller proportion of advanced students than our economic competitors—in some cases far smaller. I include some representative data in the figure below (Finland did not test eighth graders, hence the missing data), and I encourage readers to look through the complete results, which are packed with important and useful information. But it is hard to find positive data about our best-performing students in this data set. (As we edited this post, the 2015 PISA results were released. They provide similar evidence.)

This shouldn’t be the least bit surprising. Despite the condescending assumption among educators and policymakers that our brightest students don’t need much attention—“they’ll do fine on their own”—we have decades of data telling us this is just plain wrong. (See this TIMSS analysis, this NAEP analysis, and this NWEA MAP study, among many, many others.) TIMSS 2015 is only the latest source that makes the case that our general neglect of advanced learning has a price. For example, on the 2015 National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), our high-quality national testing program, 7 percent of fourth-grade students, 8 percent of eighth-grade students, and 3 percent of twelfth-grade students performed at the advanced level in mathematics in 2015. As a former science teacher, I found the science data to be even more disturbing: 1 percent advanced in grade 4, 2 percent in grade 8, and 2 percent in grade 12.

When I share these and similar data, critics occasionally argue that the standard for advanced performance on these tests is too high. Ignoring the fact that the standards don’t appear to be too high for students in other countries, the descriptors, sample items, and item maps available for TIMSS and NAEP strike me as evidence that the standards are hardly lofty. Indeed, in looking over these item maps, I was surprised that “advanced” wasn’t more advanced.

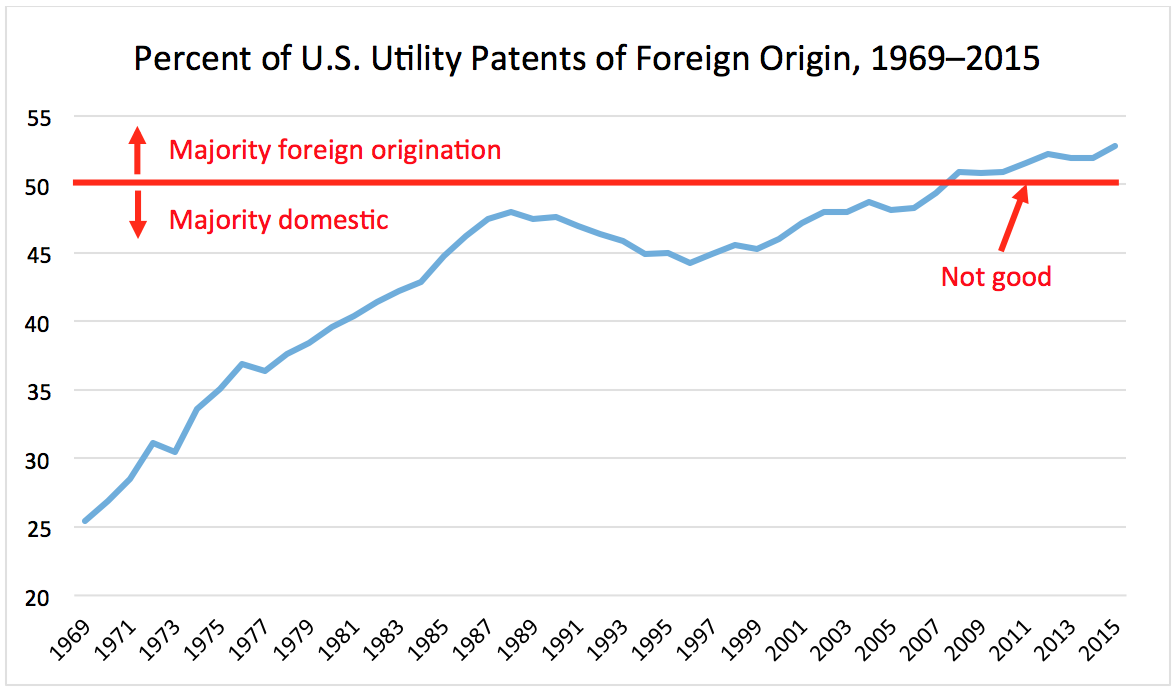

Some have long predicted that turning a blind eye toward advanced learning was going to have serious long-term consequences. I would argue that the evidence of these consequences is all around us, but we haven’t acknowledged it yet. Take, for example, the percent of U.S. patents going to people living outside of the United States:

That’s right, people in the U.S. currently receive less than half the patents issued by our government. That feels like a dangerous trend for a leading indicator of American innovation and economic development. I’m sure people can provide plenty of excuses (or rationalizations) for why this trend isn’t as bad as it looks, but it sure looks pretty bad.

Winston Churchill allegedly said, “Americans can always be counted on to do the right thing…after they have exhausted all other possibilities.” Although this quote is probably apocryphal, a biographer noted that Churchill almost certainly believed this to be true, and we’re proving it true again right now.

We have exhausted all other possibilities. One can even argue that we’ve actively lowered the quality of education for our best students by removing ability grouping, overvaluing “differentiation” as a miracle intervention, and making advanced performance irrelevant to school and district ratings in most state accountability systems. The data make it clear that we are paying the price for this mix of inattention and hostility toward educational excellence. It’s time to “do the right thing,” and a good first step is to ensure that the ESSA flexibility for acknowledging the presence of advanced performance is fully reflected in each and every state’s K–12 accountability system.

Jonathan Plucker is the inaugural Julian C. Stanley Professor of Talent Development at Johns Hopkins University and a member of the National Association for Gifted Children board of directors.