AYP, or “adequate yearly progress,” has become one of the most derided parts of the federal No Child Left Behind Act, and the accountability requirements it set in motion for states. Simply put, a school makes AYP if it is progressing adequately enough toward meeting NCLB’s goal of having 100 percent of children proficient in key tested subjects by 2014, and fails to meet AYP if it isn’t. States set annual targets and have different methods for calculating whether schools are meeting these targets. Ohio, for example, is one of nine states under the federal “Growth Model Pilot Project” allowed to incorporate its growth model into AYP calculations.

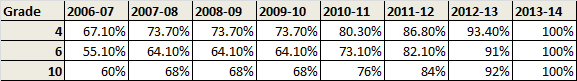

But meeting AYP is like trying to ride an escalator that speeds up with each step you take. Most states set fairly low proficiency targets in earlier years, and steeper ones in the years leading up to 2014 – making it increasingly difficult to meet targets and more likely to be labeled as failing. Take a look at Ohio’s changing target proficiency rates for math in a handful of grades over the past five years (and looking ahead to 2014).

Target proficiency rates in math among Ohio’s fourth, sixth, and tenth graders over time

Source: Ohio Department of Education website

Clearly, each year it gets harder for schools to meet these targets. Even those schools serving kids well will have an increasingly difficult time of getting the last 15, 10, or five percent of students to proficiency. On a national level, Secretary Duncan predicted earlier this year that as many as 80+ percent of schools could fail to meet AYP.

Pointing out this unfairness - and AYP’s lack of utility, really – has become a common meme in education circles. And it’s intuitive, like the law of marginal returns and the line graph that extends into infinity. Most educators and policy people alike – even those who have high expectations for poor kids – admit that 100 percent proficiency is impossible.

But how heinously inaccurate is the AYP measure when you really break it down? How many schools might be mislabeled?

In Ohio, among the top-performing schools and among the bottom tier alike, it’s surprisingly accurate according to a rudimentary glance at the data. Using data from the recent 2010-11 report cards, we looked at schools statewide that were both low growth (according to Ohio’s value-added data, so only those schools serving some combination of grades 3-8) and low achieving (those with a performance index score of less than 80 out of 120, which indicates the schools’ students are not meeting overall proficiency targets).

Eighty-four schools statewide were low growth and low achieving. Of these, 74 of them failed to make AYP and just six managed to eke by under the metric. Those that were poorly performing but did make AYP did so through the Safe Harbor provision (just one of them) and Ohio’s growth model (four of them). One school met AYP via both escape routes.

So for the poorly performing tail end of schools, AYP was largely accurate. But what about the best schools, the ones allegedly penalized by rapidly increasing expectations as we hurdle toward 2014? We looked at schools that had performance index scores above 100 (the state’s goal) out of 120, and that met or exceeded value-added growth expectations. Of these 832 schools, 735 (88 percent) met AYP. Twelve percent of these schools, then, could miss AYP and possibly be unfairly penalized, though Ohio’s accountability system has few sanctions for those schools that are otherwise deemed “Excellent” or “Effective” but miss AYP. (The only really adverse impact is missing out on a bump up in ratings.)

This doesn’t mean that NCLB isn’t in desperate need of an overhaul, or that AYP should be a mainstay in the next iteration of the law – especially among states like Ohio with so many other useful achievement indicators. However, at least for now we know that among the best schools in the state, relatively few are missing AYP. And among failing schools, most of them merit their AYP label.