The Cincinnati Enquirer recently published a deeply flawed and misleading “analysis” of the EdChoice scholarship (a.k.a. voucher) program. Rather than apply rigorous social science methods, education reporter Max Londberg simply compares the proficiency rates of district and voucher students on state tests in 2017–18 and 2018–19. Based on his rudimentary number-crunching, the Enquirer’s headline writers arrive at the conclusion that EdChoice delivers “meager results.”

Fair, objective evaluations of individual districts and schools, along with programs such as EdChoice, are always welcome. In fact, we at Fordham published in 2016 a rigorous study of EdChoice by Northwestern University’s David Figlio and Krzysztof Karbownik that examined both the effects of the program on public school performance—vouchers’ competitive effects—and on a small number of its earliest participants. But analyses that twist the numbers and distort reality serve no good. Regrettably, Londberg does just that. Let’s review how.

First, the analysis relies solely on crude comparisons of proficiency rates to make sweeping conclusions about the effectiveness of private schools and EdChoice. In addition to declaring “meager results for Ohio vouchers,” the article states that “private schools mostly failed to meet the academic caliber set by their neighboring public school districts.” No analysis that relies on simple comparisons of proficiency rates can support such dramatic judgments. Proficiency rates do offer an important starting point for analyzing performance, as they gauge where students stand academically at a single point in time. But as reams of education research has pointed out, these rates tend to correlate with students’ socioeconomic backgrounds, meaning that schools serving low-income children typically fare worse on proficiency-based measures. No one, therefore, thinks that it’s fair to assess the “effectiveness” of Cincinnati and the wealthy Indian Hills schools based solely on proficiency data.

To offer a more poverty-neutral evaluation, education researchers turn to student growth measures, known in Ohio as “value-added.” These methods control for socioeconomic influences and give high-poverty schools credit when they help students make academic improvement over time. Thus, by looking only at proficiency, the Enquirer analysis ignores private schools that are helping struggling voucher students catch up. To be fair, Ohio does not publish value-added growth results for voucher students (though it really should). Nevertheless, definitive claims cannot be made about any school or program based on proficiency data alone. It risks labelling schools “failures” when in fact they are very effective at helping low-achieving students learn. Lacking growth data, the Enquirer should have demonstrated more restraint in its conclusions about the quality of the private schools serving voucher students, and the program overall.

Second, the analysis mishandles proficiency rate calculations and skews the results against vouchers. Even granting that proficiency rate comparisons are a possible starting point, Londberg makes a bizarre methodological choice when calculating a voucher proficiency rate. Instead of comparing proficiency rates of district and voucher students from the same district, he calculates a voucher proficiency rate for the private schools located in a district. Because private schools can enroll students from outside the district in which they’re located, his comparison is apples-to-oranges. Londberg’s roundabout method might be justified if the state didn’t report voucher results by students’ home district. The state, however, does this.[1]

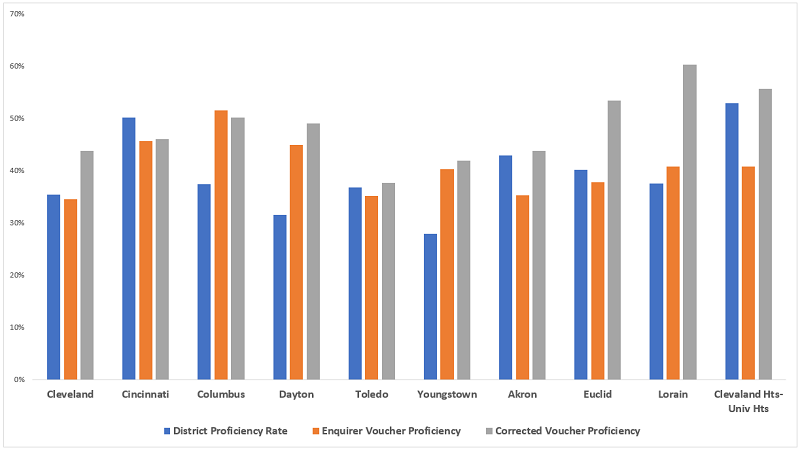

As it turns out, the method matters. Consider how the results change in the districts with the most EdChoice[2] students taking state exams, as illustrated in Figure 1. The gray bars represent a “corrected” calculation of voucher proficiency rates based on pupils’ district of residence. In several districts, the right approach yields noticeably higher rates than what the Enquirer reports (e.g., in Cleveland, Akron, Lorain, and Cleveland Heights-University Heights). In some cases, the correct method changes an apparent voucher disadvantage into an advantage in proficiency relative to the district. For example, vouchers are reported as underperforming compared to the Euclid school district under the Enquirer method. But in reality, Euclid’s voucher students—the kids who actually live there—outperform the district.[3]

Figure 1: Voucher proficiency rates calculated under two methods in the districts with the most EdChoice test-takers, 2017–18 and 2018–19

Notes: The blue and orange bars are based on the Enquirer’s calculations of district and voucher proficiency rates. The gray bars represent my calculations based on the Ohio Department of Education’s proficiency rate data that are reported by voucher students’ home district.

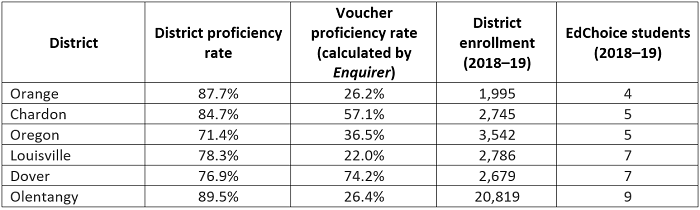

Third, it makes irresponsible comparisons of proficiency rates in districts with just a few voucher students. Due in part to voucher eligibility provisions, some districts (mainly urban and high-poverty) see more extensive usage of vouchers, while others have very minimal participation. In districts with greater voucher participation—places like Cincinnati, Cleveland, and Columbus—it makes some sense to compare proficiency rates (bearing in mind the limitations in point one). It’s less defensible in districts where EdChoice participation is rare to almost non-existent. Londberg, however, includes low-usage districts in his analysis, and Table 1 below illustrates the absurd results that follow. Orange school district, near Cleveland, posts a proficiency rate that is 50 percentage points higher than its voucher proficiency. That’s a big difference. But it’s silly to say that the voucher program isn’t working in Orange on the basis of just a few students. It’s like saying that LeBron James is a terrible basketball player due to one “off night.” Perhaps this small subgroup of students was struggling in the district schools and needed the change of environment offered by EdChoice. Moreover, it’s almost certain that, had more Orange students used a voucher, proficiency rates would have been much closer.

Table 1: District-voucher proficiency rates comparisons in selected districts with few EdChoice students

Note: The Enquirer voucher proficiency rate is based on students attending private schools in that district—it did not report n-counts—not the number of resident students who used an EdChoice voucher (what’s reported in the right-most column above). The EdChoice students in the table above are low-income, as they used the income-based voucher.

Things, alas, go from bad to worse in terms of the results from low-usage districts. In an effort to summarize the statewide results, Londberg states, “In 88 percent of the cities in the analysis, a public district achieved better state testing results than those private schools with an address in the same city.” That statistic is utter nonsense. It treats every district as an equal contributor to the overall result—a simple tally based on whether the district outperformed vouchers—despite widely varying voucher participation. The unfavorable voucher result in Orange, for instance, is given the same weight as the favorable voucher result from a district like Columbus where roughly 5,500 students use EdChoice. That’s hardly an accurate way of depicting the overall performance of EdChoice.

***

Londberg’s amateur analysis of EdChoice belongs in the National Enquirer, not a feature in a well-respected newspaper such as the Cincinnati Enquirer. Unfortunately, however, this piece is sure to be used by voucher critics to attack the program in political debates. As this “analysis” generates discussion, policymakers should bear in mind its vast shortcomings.

[1] A Cleveland Plain Dealer analysis from earlier this year looks at voucher test scores by district of residence.

[2] For Cleveland, the results are based on students receiving the Cleveland Scholarship.

[3] Another oddity of the Enquirer method is that a number of districts with relatively heavy voucher usage are excluded from the analysis. For example, Maple Heights (near Cleveland) and Mount Healthy (near Cincinnati) have fairly large numbers of EdChoice recipients, but they are excluded because there are no private (voucher-accepting) schools located in their borders.