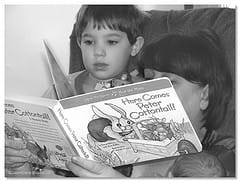

Research has long shown that reading comprehension and vocabulary are well correlated. Photo by ?erry via photopin cc. |

While there are achievement gaps between low-income and affluent students across content areas, none seem more vexing to close than the reading gap. While the enormous investment of time and resources that was poured into the Reading First initiative resulted in modest gains, particularly at the elementary level, we have not made the progress we had hoped for in either improving reading achievement or closing the comprehension gap.

There are no doubt a host of factors that contribute to this gap in reading, not least of which the fact that low-income students are far less likely to be read to and talked to in the early years, or to be exposed to the kind of content-rich curriculum they need to build knowledge and expand vocabulary—both critical drivers of reading comprehension.

Research has long shown that reading comprehension and vocabulary are well-correlated. The results from the latest NAEP vocabulary assessment provide additional ammunition to those who argue that if we ever hope to address the reading gap, we must find a way to address the language and knowledge gap between our lowest- and highest-performing students. Specifically, the NAEP results show the following:

- Fourth-grade students performing above the 75th percentile in reading comprehension in 2011 also had the cohort’s highest average vocabulary scores.

- Lower-performing fourth-graders at or below the 25th percentile in reading comprehension had the lowest average vocabulary score.

- The patterns are similar for grade 8 in 2011 and for grade 12 in 2009. (Grade 12 was not assessed in 2011.)

Of course, E.D. Hirsch has long argued that once students learn how to read in the early years, they need broad and systematic exposure to the kind of curriculum that will help them build the knowledge and vocabulary they need. Studies have shown that our most disadvantaged students tend to be read to less, talked to less, and generally exposed to far less sophisticated vocabulary and sentences. Worse, because it is far easier to build knowledge and vocabulary once you have knowledge, these gaps only increase through the years, further disadvantaging our most struggling students.

How can we address this worrisome vocabulary gap? As Hirsch reluctantly acknowledges, since “word rich” children will always be able to acquire language (and content knowledge) more easily than “word poor” children, we may never completely close the gap. Worse still, because the most effective way to increase vocabulary is through multiple “incidental” exposures to the kinds of rigorous, academic, content-specific vocabulary that students need to drive comprehension, explicit vocabulary instruction can only make a small dent in closing the word gap.

Instead, Hirsch argues that since “acquiring word knowledge and domain knowledge is a gradual and cumulative process” and since “early learning of words and things is the only way to overcome early disadvantage, the argument for including optimal content in language arts as early as possible seems compelling.” More specifically, we should focus, as early as possible, on developing “oral comprehension” (through read-alouds, exposure to complex sentences and words) and on exposing all students—particularly our most disadvantaged—to content-rich curriculum as early as possible.