NOTE: The Thomas B. Fordham Institute occasionally publishes guest commentaries on its blogs. The views expressed by guest authors do not necessarily reflect those of Fordham.

There’s no doubt about it: We have a graduation rate problem in the United States. However, one of the biggest problems might not be what you think. It is not simply the hundreds of thousands of students failing to graduate on time or the hundreds of thousands of graduates who leave high school but still require remediation upon postsecondary enrollment. One of the most challenging yet least talked about problems is the four-year cohort graduation rate calculation itself.

While students are enrolled in a typical high school for four years—grades nine to twelve—the four-year cohort graduation rate calculation waits until the fourth year to account for their progress toward graduation. After four years, a student is stamped with a one-time designation of “graduated on time” or “did not graduate on time.”

That approach makes sense in a world in which students attend the same high school all four years. But in an increasing number of communities, that is no longer the world we live in. Especially with the advent of online schools and other choice options, many students now attend multiple schools over the course of their high school experience. Yet only the school that last enrolled a student is evaluated for her success or failure.

A recent report by the Thomas B. Fordham Institute said of students who transfer high schools:

“Receiving schools become fully accountable for transfer students’ on-time graduation, though they may have fallen significantly behind while in their former school. High schools that enroll large numbers of credit-deficient students are especially at risk of low ratings when this calculation is utilized.”

The example outlined below illustrates how failure by schools in the first three years of high school can be masked in year four when students transfer.

[[{"fid":"119853","view_mode":"default","fields":{"format":"default"},"link_text":null,"type":"media","field_deltas":{"1":{"format":"default"}},"attributes":{"class":"media-element file-default","data-delta":"1"}}]]

Waiting until year four to capture a student’s graduation status may make sense for schools where the student population is relatively stable. But what happens if a school receives dozens of new high school students each year? Or maybe even hundreds? An analysis of fourteen online schools of varying sizes, geographic locations, and student populations found that more than half of all high school students were new to those schools in 2015-16. Of those newly enrolled students, 50 percent of them arrived credit deficient. This means that the students fell behind in a prior school and are off track for an on-time graduation, yet the prior school faces no accountability for their failure.

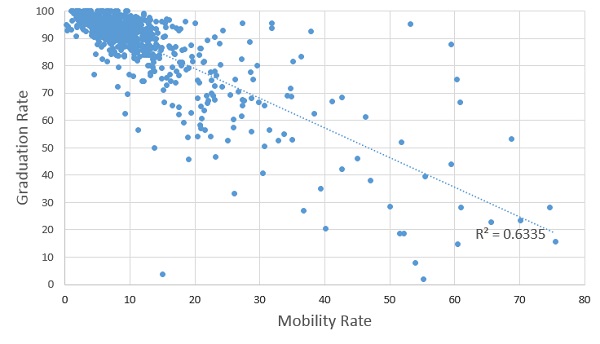

In Ohio, schools with more than 25 percent of enrolled students enrolling in or out are called highly mobile schools. For these schools, the four-year cohort graduation rate metric skews especially negative due in part to the instability of the student population, as evidenced below in the analysis of highly mobile schools compared to traditional schools in the state of Ohio.

[[{"fid":"119855","view_mode":"default","fields":{"format":"default"},"link_text":null,"type":"media","field_deltas":{"3":{"format":"default"}},"attributes":{"class":"media-element file-default","data-delta":"3"}}]]

Using the Ohio data, it becomes very apparent that there is a negative relationship between graduation rate and mobility rate—meaning the higher the mobility rate, the lower the graduation rate. In fact, highly mobile schools have an average graduation rate that is 31 percentage points lower than that of less mobile schools. While some of this could be due to other student factors like income status, there is no doubt that the relationship between school mobility rates and graduation rates is more than just chance. These data lead to the question: Are we truly measuring how successfully a school is improving students’ ability to graduate on time, or are we simply calculating a rate that reflects the mobility of the student population?

Furthermore, have we created a perverse incentive for brick-and-mortar high schools to encourage their under-credit students to transfer to online schools in order to inflate their graduation rates?

Given this analysis, we need to rethink our approach to graduation rate and take a more student-centered approach. We have two recommendations.

First, instead of waiting to capture a graduation status for a student after year four, hold schools accountable for adequate progress toward graduation for all students in year one, two, three, and four. Measuring annual progress toward graduation for every student ensures that every school is accountable for the progress (or lack thereof) of every student every year. For more about this approach, read the four-part series here.

Second, in addition to the four-year cohort graduation rate, calculate a graduation rate for each school that only accounts for students served by the school for all four years, starting in ninth grade. Doing this ensures a level playing field for highly mobile schools and allows for more equitable comparisons between all schools. Going back to the fourteen online schools serving highly mobile populations, utilizing the traditional four-year cohort calculation would result in a 40 percent graduation rate. However, calculating the rate for only students enrolled for all four years would result in a rate double that at 80 percent.

Before we can even begin to address many of the other graduation rate problems that we face in the United States, it is absolutely imperative that we ensure we are utilizing the proper metrics to measure student and school success. We join our voices with the Fordham report and call on state lawmakers, both in Ohio and elsewhere, to explore graduation rate calculations that hold high schools accountable for what is under their control. Make every student matter, every year, for every school, in every state.

Jessica Shopoff, M.Ed. and Chase Eskelsen, M.Ed. are on the Academic Policy and Public Affairs teams for K12 Inc., an online learning provider.