Editor’s Note: The Thomas B. Fordham Institute occasionally publishes guest commentaries on its blogs. The views expressed by guest authors do not necessarily reflect those of Fordham.

In early May, Columbus City Schools released a searing 450-page external audit that took the district to task and called for improvement on many dimensions of governance and performance. Some of the most alarming findings, in my view, concern the failure of the district’s teacher evaluation process.

Last year, only two of the district’s roughly 3,500 teachers were rated as “ineffective” on their official evaluations, and only about 5 percent received the second-lowest “developing” rating, according to district data. But when auditors asked school principals for their honest opinions, more than a third reported that at least 10 percent of the teachers in their schools were ineffective. In some buildings, principals rated nearly 20 percent of their teachers as ineffective. “That’s the highest I’ve ever seen, I was shocked to see that!” the lead auditor told the school board in her presentation of the findings.

There are devastating implications for the thousands of Columbus students assigned to ineffective teachers. Yet the audit findings also raise serious questions about the state’s investment in the Ohio Teacher Evaluation System, the framework used by Columbus in recent years. Unless district leaders learn from the failings of the past system, the audit bodes ill for the revamped evaluation system (dubbed OTES 2.0) that will be rolled out in the coming months. Consider the following three lessons.

Lesson 1: Using locally designed assessments and metrics can lead to inflated performance ratings

Ohio’s teacher evaluation system was first implemented as a response to the Obama administration’s signature Race to the Top competition. The federal initiative was based on two striking findings that were emerging from education policy research at the time. The first showed that, despite the importance of teachers in improving student achievement and substantial variation in their effectiveness, existing evaluation systems failed to differentiate teachers based on their ability to improve student learning. Instead, more than 99 percent were consistently being rated as “satisfactory” regardless of how well their students actually performed. The second finding suggested that a class of statistical models, known as “value-added,” could accurately and reliably identify teachers that were doing the best and worst job of improving student achievement as measured by standardized test scores.

To remain competitive for federal funds, states were required to develop evaluation systems that could differentiate teacher effectiveness and were based, at least in part, on student achievement growth, as measured by value-added models. Since Ohio already had a value-added system in place, it was well positioned to incorporate this information into its new teacher evaluation system.

The original OTES model based half of a teacher’s overall evaluation on student growth. But the problem is that value-added information is available for only a small subset of teachers—those teaching subjects and grades included in annual state tests, which are primarily math and English language arts in grades four through eight. It turns out that 80 percent of Ohio’s teachers don’t receive a value-added designation from the state, and even those who do also teach other subjects that are not covered on state tests. To address these gaps, the state implemented a process for teachers to create their own tests and metrics—called “student learning objectives” (SLOs)—to document their impact on student learning.

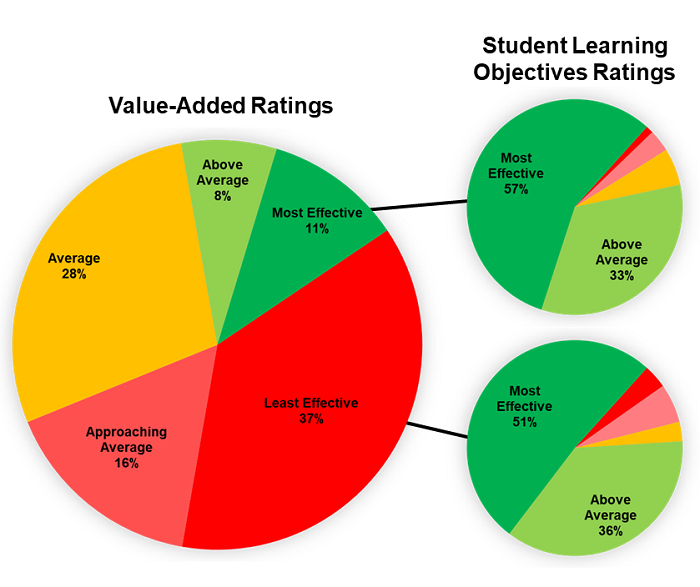

The flaw with SLOs, however, was that individual teachers in effect got to decide how their performance in improving achievement would be measured and evaluated, a system obviously vulnerable to abuse. As the Columbus audit and district data show, teachers have taken full advantage of SLOs to inflate their scores. Consider the roughly 1,000 Columbus teachers who received a state “value-added” designation last year. More than half were rated as below average by the state, and 37 percent received the “least effective” designation based on their ability to raise student achievement on state tests. Because few educators exclusively taught subjects covered by the value-added measure, the vast majority were able to incorporate SLOs into their evaluation calculation. As a result, more than three-quarters of these least-effective teachers were still rated as above-average, and half were rated “most effective,” using teacher-designed SLOs. Indeed, as the Figure 1 reveals, educators whose students demonstrated the least amount of growth on state tests look essentially identical to teachers who improved student achievement the most when we compare them using SLOs.

Figure 1. Comparing value-added and SLO measures of student growth for Columbus teachers (2018–19)

Although the state put in place requirements to ensure that teachers developed valid SLOs, and Columbus appointed committees to review them, it turned out that it is almost impossible to effectively police this process. As one Columbus principal told the auditors, “Teachers could more or less make stuff up for the data part of the teacher evaluations.”

For illustration, consider one Columbus teacher who was rated as “least effective” through value-added, but who received the highest possible student growth rating using SLOs last year. One of her SLOs was based on the book Word Journeys, an impressive framework that divides the development of orthographic knowledge into stages, from “initial and final consonants” to “assimilated prefixes.” The book comes with a screening tool composed of twenty-five spelling words designed to cover each of the stages, and this teacher’s SLO set the goal of increasing the number of words each student spelled correctly between the beginning and end of the year by twelve. Not surprisingly, every student met or exceeded this target.

The problem is that it is impossible to know whether student spelling in this class improved because the teacher did a great job teaching the underlying skills—each of the stages in the Word Journeys framework—or because the teacher simply had students memorize twelve of the twenty-five words she knew made up the book’s screening tool. The former is true learning, while the latter is the very epitome of teaching to the test—a test that teacher herself got to handpick.

Thus, the SLOs were a true Achilles’ heel in the state’s old teacher evaluation system. While OTES 2.0 scraps SLOs, I worry that similar problems will emerge with the alternative growth measures that will replace them.

Lesson 2: Principals need incentives and time to do evaluations right

Under Ohio’s old evaluation framework, student growth—measured either through value-added or SLOs—accounted for only half of each Columbus teacher’s overall evaluation score, and even less in some other districts. The second half came from principal observations. Historically, observations were perfunctory exercises using simple checklists, but to win Race to the Top funds, states had to create much more thorough rubrics. Ohio developed a rubric called “Standards for the Teaching Profession.”

Despite the well-defined criteria on the rubric, Columbus principals appear to have been quite lenient in their evaluations. For example, among Columbus teachers identified as “least effective” by the state through value-added last year, principals rated 90 percent of the educators they observed as “skilled” or “accomplished,” the two highest categories.

Of course, it’s possible that principals were looking at broader aspects of teacher skill and quality not captured by test scores. However, it seems more likely that many principals just didn’t follow the rubric. As one Columbus principal told the auditors, “I don’t use the actual teacher evaluation; it’s very cumbersome. I just fake it.”

I suspect there are two primary reasons many principals failed to embrace the state’s observation protocol. First, the job of a principal in a low-performing, urban district is already overwhelming. From managing student behaviors to taking care of other responsibilities, it seems unrealistic for most principals to find the necessary time in their packed schedules to thoroughly observe and carefully evaluate every teacher with the effort and diligence the process truly requires.

Second, the ability of teachers to inflate their overall ratings using SLOs made the principals’ evaluations pretty toothless. Consider the example I describe above, wherein the teacher’s SLO set the goal of her students spelling twelve words correctly. Not only was the teacher identified as “least effective” by the state based on value-added, she was also rated as “developing” by her principal, the second-lowest possible observation category. Yet, because of her stellar SLO scores, the teacher earned an overall rating of “skilled,” the second-highest available. Knowing that teachers would use SLOs to inflate their final scores, there was little incentive for principals to be critical or honest in their own evaluations since they would not be able to replace the ineffective teachers. Doing so just created unnecessary conflict and awkwardness in their buildings, hardly an outcome that benefited students or made the school better.

Lesson 3: Tie evaluation to teacher support, professional development

Of course, the purpose of evaluations is not simply to identify struggling teachers. It’s also to help them improve when possible, and replace them with someone better if they fail to make progress. Ohio’s Race to the Top grant application assured that “performance data will inform decisions on the design of targeted supports and professional development to advance their knowledge and skills as well as the retention, dismissal, tenure and compensation of teachers and principals.” In practice, none of these appear to have happened in Columbus.

Since SLOs made it almost impossible for teachers to receive the “ineffective” rating, teachers didn’t have to worry about dismissal. More importantly, there is little evidence that the evaluation and observation process helped low-performing teachers improve their craft.

Part of the problem is that principals provided struggling teachers with little useful feedback. As the auditors noted, “the comments recorded on the teacher evaluation instruments by the administrators were generally not constructive.” When examining teacher improvement plans—the actionable product that is supposed to emerge from the evaluation process and guide future instructional improvement—the auditors found “that the goals were written by each teacher, and there was no connection between the comments made by the administrator and the goals and action steps written by the teacher.”

Although former Columbus Superintendent Dan Good sought to achieve better alignment between the district’s professional development spending and its teachers’ actual needs by decentralizing funding and control to individual schools, the auditors found little evidence that the investments were being targeted effectively or producing any measurable returns in terms of better teaching. “The auditors found that professional development in the Columbus City Schools is site-based, uncoordinated, inconsistently aligned to priorities and needs, and rarely, if ever, evaluated based on changed behaviors,” they wrote.

Lessons for OTES 2.0 and Beyond

Is Columbus an outlier? Or is its experience symptomatic of broader problems with the theory of action on which the first iteration of Ohio’s teacher evaluation process was based? The available evidence suggests the latter—and not just in Ohio.

To our state’s credit, Ohio policymakers have recognized many of the issues documented in the Columbus audit, and have attempted to address them in the development of OTES 2.0, which is being rolled out across the state over the coming months. The updated framework eliminates the standalone student growth metric, embedding the assessment of growth with the principal observations instead. It also replaces SLOs with a requirement that district use “high quality student data.” However, I’m pessimistic that the new system will prove to work substantially better than the old one.

First, there is no reason to think that principals will have any more time to complete thorough evaluations or greater incentive to be honest when critical but constructive feedback is deserved than they did under the old model or in the pre-OTES 1.0 days. Second, it seems likely that many district will turn to “district-determined instruments” to assess student learning. As with the SLOs, district officials will likely face considerable pressure from teacher unions to make these assessments easy and highly predictable. If these new assessments rely on relatively shallow question banks, teachers will again be tempted to respond strategically and teach very narrowly to the tests, without realizing broader improvements in student performance. Third, districts like Columbus will surely continue to struggle to deliver sufficiently targeted professional development and other supports that are necessary to address the diverse needs of struggling teachers.

Of course, I hope I’m wrong. Columbus students cannot afford another lost decade.

Vladimir Kogan is an associate professor at the Ohio State University Department of Political Science and (by courtesy) the John Glenn College of Public Affairs. The opinions and recommendations presented in this editorial are those of the author and do not necessarily represent policy positions or views of the John Glenn College of Public Affairs, the Department of Political Science, or the Ohio State University.