Over the past two years, the Cupp-Patterson school funding plan has received tremendous attention in the media and at the statehouse. Currently, House lawmakers are considering what changes might be made to the plan, as laid out in House Bill 1. Despite all the hoopla and multiple iterations of the proposal, important details still need to be ironed out. The public hasn’t yet been informed about how the state will pay its $2 billion price tag, funding for public charter schools and independent STEM schools remains inequitable, and the base cost model could create headaches for future lawmakers. Two additional issues, not yet discussed on this blog, also deserve further scrutiny: interdistrict open enrollment and guarantees.

Interdistrict open enrollment

More than 80,000 students today use interdistirct open enrollment to attend public schools in neighboring districts. Under current policy, the funding of open enrollees is fairly straightforward. The state subtracts the “base amount”—currently a fixed sum of $6,020 per pupil—from an open enrollee’s home district and then adds that amount to the district she actually attends. Apart from some extra state funds for open enrollees with IEPs or in career-technical education, no other state or local funds move when students transfer districts.

In a wider effort to “direct fund” students based on the districts and schools they actually attend, the Cupp-Patterson plan eliminates this funding transfer system for open enrollment. In the new plan, open enrollees receive the same level of state funding as resident pupils in that district—not a set amount that applies anywhere in the state. While this seems to make sense at face value, the approach results in significantly lower funding for most open enrollees relative to current law. The upshot: These reductions are likely to decrease participation in open enrollment, and they will remove valuable public school options for Ohio families and students.

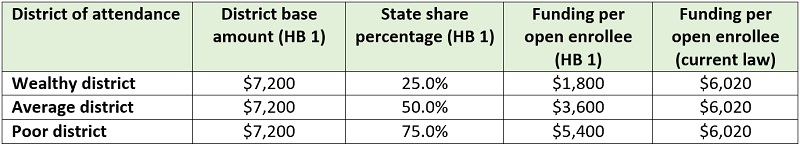

The table below illustrates how it would work. To ensure an equitable distribution of state money, HB 1 applies the state share percentage (SSP) to districts’ base amounts. Wealthy districts have a lower state share—they have the capacity to raise large sums locally—while the state picks up a larger portion of the tab in poorer districts. Applying the SSP to open enrollment funding would mean that a student choosing to attend a wealthy district might generate just $1,800 of state funds—instead of $6,020. While the SSPs are higher as wealth decreases, funding for open enrollees under HB 1 also falls below current levels when they attend average poverty districts and most high-poverty ones.

Table 1: Illustration of open enrollment funding under House Bill 1

Note: Base amounts are not determined by districts’ wealth and, with some exceptions, do not vary widely across districts. The statewide average base amount under a fully implemented plan is $7,199 per pupil. The state share percentage (SSP), however, varies by district wealth (property values and resident income) and ranges from 4.4 to 90.1 percent. Much like the current funding model, the SSP adjusts a district’s base amount for its local wealth to yield the state funding obligation for the core formula component.

The Cupp-Patterson approach to funding open enrollment would make sense if the state required the local share of the base amount to “follow” students to their district of attendance. But it doesn’t. The local funds designed for an open enrollee’s education stays in her home district. As a result, HB 1 significantly cuts open enrollee funding. These reductions not only underfund students’ education, but also drastically weaken the incentive for districts to accept open enrollees, especially high-wealth districts that could offer less advantaged students seats in their classrooms.

To address this problem, legislators have two options. First, they could revert open enrollment funding to the current model whereby all open enrollees receive the full base amount, whether that’s a fixed statewide amount or the one that applies to her district of residence or attendance. Though more politically challenging, lawmakers could alternatively require the local share of an open enrollee’s base amount to transfer from her home district to the district she attends.

Guarantees

Ohio has long debated “guarantees,” subsidies that provide districts with excess dollars outside of the state’s funding formula. These funds are typically used to shield districts from losses when the formula calculations prescribe lower amounts due to declining enrollments or increasing wealth. In FY 2019—the last year in which funds were allotted via formula—335 of Ohio’s 609 school districts received a total of $257 million in guarantee funding, representing about 2.5 percent of state K–12 education expenditures.[1] Worth noting is that the guarantee isn’t directly tied to poverty. A number of high-wealth districts benefit from the guarantee, including affluent suburban districts such as Brecksville-Broadview Heights, Mason, and Upper Arlington.

While guarantees may be politically convenient, they cause problems. For starters, they undermine the state’s funding formula, whose aim is to allocate dollars efficiently to districts that most need the aid. Districts on the guarantee receive funds above and beyond the formula prescription, while others must be content with the formula amount—sometimes even less. Many critics, including proponents of the Cupp-Patterson plan, have called this system unfair due to the piecemeal approach. Just as concerning is the way guarantees fund a certain number of “phantom students” when state money would be better used to meet the needs of real students.

Among the main ideas of the Cupp-Patterson plan is to create a fair funding system and to drive education dollars to the schools that students actually attend. Those are the right concepts and we might therefore expect the proposal to eliminate guarantees. Though the plan does make a slight improvement to the state’s guarantee structure, it does not put an end to it. In fact, Cupp-Patterson adds a few new measures that function just like guarantees. Consider the following:

- HB 1 would move Ohio to per-pupil guarantees, rather than ones based on absolute funding levels. Generally, under current policy, the state compares a district’s funding from a prior year (say $6 million) to the formula prescription for the current year ($5 million). The difference represents the guarantee amount the district receives ($1 million). Under HB 1, districts are guaranteed the per-pupil state funding they received three years earlier; e.g., $5,500 (prior year)minus $5,000 (current year)= $500 per pupil guarantee.[2] By moving to a per-pupil guarantee, the plan likely alleviates concerns about funding phantom students.[3] That being said, it would still funnel excess money to districts outside of the formula, thus falling short of a system that funds all districts strictly according to the formula.

- In a new funding stream known as “supplemental targeted assistance,” the plan also sends excess money outside of the formula to districts that have lost significant numbers of students to choice programs. Low-wealth districts where more than 12 percent of resident students attended public charter schools or used private-school vouchers in 2019 would receive an annual bump in state funding, anywhere from $75 to $750 per pupil. This new policy, which is more akin to funding phantom students, would send a total of $56 million per year to thirty-six Ohio districts.

- Though not a guarantee in a traditional sense, the Cupp-Patterson plan includes something like it in its base cost model. There we find that school districts (though not charter schools) are guaranteed a minimum number of special teachers and SEL staff, even when the plan’s specified staff-to-enrollment ratios prescribe lower numbers. Such minimums would significantly enrich small districts—those with less than 1,000 students—as base costs skyrocket, thus creating a small-district subsidy. In sum, these minimums function like a guarantee because they allocate funds to districts outside of a formula—this time, the base cost formula.

All told, the Cupp-Patterson plan is a mixed bag on guarantees. On the one hand, it does transition Ohio to a per-pupil guarantee—a second-best option after eliminating them entirely. On the other hand, the plan takes two steps backwards with its subsidy for districts with large numbers of choice students and allowing for minimum staffing levels in its base-cost model.

***

Many of the concepts behind the Cupp-Patterson plan are commendable, but the translation of these ideas into concrete funding policies seems more questionable. The developers have aimed for a “fair funding” plan, yet still seem to treat the thousands of Ohio students exercising school choice options as an afterthought. And while its architects have also talked about funding all districts fairly—according to the state’s own formula—the plan continues to carve out special exceptions that deliver excess dollars to lucky districts. In the end, the plan’s details don’t always seem to square with its lofty ambitions. In the coming days, legislators should work to right these all-important details.

[1] Due to concerns about the current funding model, state lawmakers suspended the formula for FYs 2020 and 2021. In FY 2019, districts with declines in their “total ADM” (which includes district, charter, and scholarship students) between FYs 2014–17 were subject to state funding losses of up to 5 percent.

[2] This guarantee goes beyond temporary “hold harmless” provisions in HB 1 as the state transitions funding models. A permanent guarantee policy would start in 2024 and be in effect for every year thereafter. LSC estimates an annual outlay of $276 million in guarantee expenditures under a fully implemented plan, though it’s not clear whether that amount includes the costs of temporary guarantees during the phase-in period.