What would happen if both sides of today’s education reform debate—the “public common school” crowd and the education reformers—got everything they wanted all at once? The newly released Student Success 2025 plan aims to envision just that for the state of Delaware.

The plan was crafted by the Vision Coalition of Delaware, led by a Who’s Who of education, business, philanthropy, and state government heavyweights. The Student Success 2025 project included dozens of additional committee members from all stakeholder areas. The project was informed by the public input of more than four thousand Delawareans, including over 1,300 K–12 students. The intent was to create a broad plan for the future of public education in the state in order to “cut through the noise” and to think big on “issues on which most people can agree.” By keeping the two sides in regular communication for a decade, the coalition has accomplished a minor miracle. The plan they have produced is reflective of that effort.

Student Success 2025 reads like a laundry list that includes universal, free, high-quality pre-K; comprehensive wraparound services for kids and families at every school; mastery-based learning with limitless remediation and acceleration as needed; mentoring; free early college courses; extensive PD and planning time for teachers and principals; budget and hiring flexibility for school leaders; internships and job placement assistance; universal access to arts, culture, and languages; charters and district schools sharing services, students, and funding; ESAs; e-schools, course choice, and blended learning; and rigorous standards and assessments balanced with alternative evaluations for students, teachers, and principals. The plan also envisions adequate funding for all these programs, including double or triple amounts for special needs and ELL students, additional funding for which has never been available in Delaware before.

Yes, it sounds like Shangri-La; but as master plans go, this one seems fantastic. It’s both coherent and complete, and it comes with tremendous buy-in from the start. A swing for the fences.

It would be easy to nitpick over details of the vision from either side of the education reform debate, but it would also be churlish. The point of the exercise was not to prioritize one method of improving education over another, but to hear everyone’s input and create a vision that could implement any and every possible school improvement strategy. It’s like taking the very top district school, the nimblest charter, the most inventive STEM school, and the poshest private school and mashing them all together. Bookend them with high-quality pre-K and college/job pipelines and wrap them in all the poverty-disrupting services that might be needed. Fund them to the hilt. Replicate and provide free of charge to all 133,000 kids in the state. What’s to dislike?

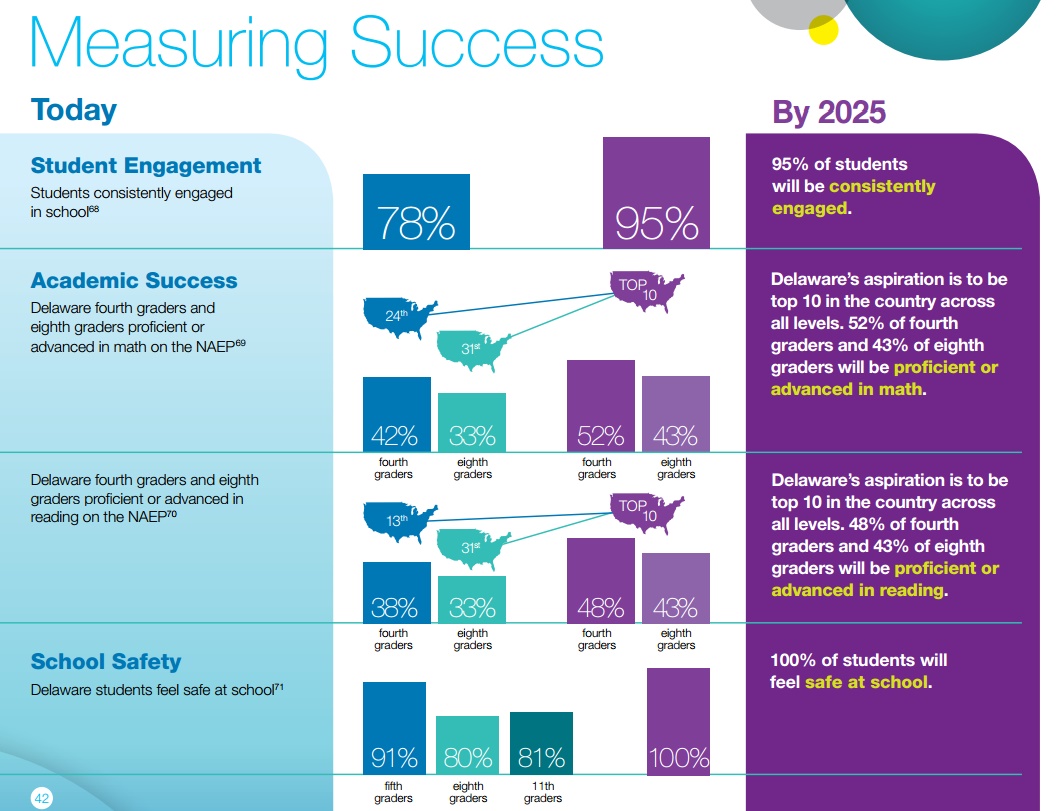

I won’t presume to answer that question for the public common school folks, but from the reform side of the education debate, the place to start is with the goals. If all of these inputs were implemented immediately and funded to the full extent required (again, no judgment here), what would Delawareans see as outputs in ten years’ time? According to the plan, the answer is less than half of their eighth graders testing proficient in math. Yes, 48 percent proficient would represent an impressive leap from the current 43 percent—enviable and desirable growth, as shown in the slide below. It would put Delaware at or near the top in terms of U.S. states and developed countries. But it is not a home run.

In the preamble of the vision document, the authors describe their mission thusly [emphasis theirs]:

That is a home run.

How does that square with more than half of students reaching the eighth grade unable to test proficient in math? Especially considering the smorgasbord of reforms and supports the plan recommends? Who are these students, and why aren’t they part of the success portion of the vision?

One possibility: they are those who don’t necessarily need school-based math proficiency to be successful. (Think performing artists, hospitality workers, professional athletes, and factory workers.) Maybe, but are more than half the student body seriously envisioned as athletes and actors? Another: the 52 percent are those who are not expected to succeed at eighth-grade math despite the plan’s enveloping supports. This seems particularly unlikely given the enormous effort envisioned here. Keep in mind that these putative eighth graders will have a full ten years of the plan’s prodigious benefits, starting at age three.

But the most likely possibility is that some hard-earned experience kept the plan’s framers from envisioning the ball actually going over the fence.

The Vision Coalition of Delaware was also responsible for the Vision 2015 plan. It was ambitious as well—arguably a precursor to Race to the Top—but not nearly as comprehensive. It was more a laying of groundwork than anything, but predicated on some lofty objectives:

In the eight years since Vision 2015’s introduction, and in the waning months of its target year, one of its architects says that they’ve implemented about three-quarters of its recommendations and seen some modest success. Perhaps the folks who know those numbers well realize that they may realistically get less than half of their 2025 recommendations implemented and have predicted success rates in line with that reality. Perhaps the cooperation among stakeholders wasn’t quite as multilateral as it seems, leading to a reduction of emphasis on “no excuses” (2015) in favor of an emphasis on inputs and “access to opportunity” (2025). Accountability seems to be baked in to the 2025 plan, but in the end I honestly think it won’t matter.

No true roadmap for statewide student success can dead-end at eighth grade. College is out, career prospects shrink, earning power diminishes, and the expense of the enterprise—whatever enormous number it might end up being—is spread among only 48 percent of students. Now that’s some depressing math. Even worse, there’s nowhere else to go from 2025 if you’ve already spent the farm and implemented every idea.

So in the end, we have a huge vision with little expected payoff from this writer’s perspective. My kids are in eighth grade right now and I want their school to push them further and harder every day. Not so they can be part of the fortunate 48 percent, but because quality education is vitally important to 100 percent of kids.

More explanation is required on the part of the Vision Coalition of Delaware as to why citizens should support a reform plan that leaves out so many, even if it sounds like Shangri-La.