The latest iteration of the Cupp-Patterson school funding plan was recently unveiled in an amendment to House Bill 305 and the introduction of a Senate companion bill. The plan still faces plenty of questions, including how to pay its $2 billion per year sticker price. One question that’s flying a little below the radar is how the latest version treats charter schools. If you recall, the initial plan gave choice programs the cold shoulder, most notably by freezing charter funding after just two years while allowing district funding to continue rising. What does the revised version of the Cupp-Patterson plan have in store for charter schools? Let’s take a look.

(Of note, this piece doesn’t look at private-school scholarships, as significant changes were recently made to these programs. We’ll save them for another time.)

Issue 1: Funding equity

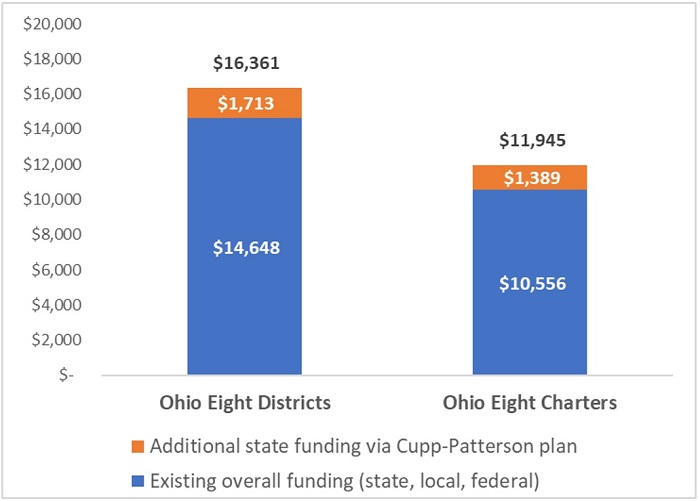

Ohio’s public charter schools have long received the short end of the school-funding stick. In the Ohio Eight—the cities where a large majority of charters are located—brick-and-mortar charters receive on average roughly $4,000 per pupil less than districts, even though they serve students of similar backgrounds.[1] Figure 1 shows that the Cupp-Patterson plan would not narrow these yawning funding gaps. In fact, it would widen them. Under a fully-funded plan, the Ohio Eight districts would see an average increase of $1,713 per pupil, versus $1,389 per pupil for charters.[2] Although charters enjoy increased funding in absolute terms, they would continue to lose ground when compared to their nearest districts, further limiting their ability to compete for talented teachers or offer comparable academic and non-academic supports.

Figure 1: District and charter per-pupil funding in the Ohio Eight cities

Note: This figure displays the average overall funding per-pupil across the Ohio Eight districts and the brick-and-mortar charter schools located in those districts in FYs 2015-17 (calculations are here). The additional state funding represents the average increases under a fully-funded Cupp-Patterson plan. The estimated increases for individual Ohio Eight districts and charter schools vary quite widely, from $652 to $3,009 per pupil on the district side and -$82 to $3,665 per pupil on the charter side.

To level the playing field for all educational models and encourage true “educational pluralism” in Ohio, a much different approach to school funding reform is likely needed. But there are three ways that the Cupp-Patterson framework could be tweaked to make funding more equitable for the students attending charter schools.

First, the plan should ensure that charter funding amounts are calculated in the same way as districts. The Cupp-Patterson plan employs extensive calculations, based on pupil-to-staff ratios, salary data, and more, that yield the “base cost” of educating a typical student. Those costs, which vary by district, are then used to determine state funding amounts. The initial version of the plan didn’t apply the base cost formula to charters; they instead received fixed amounts. To the extent that districts are funded via a base cost model, the updated plan rightly moves charter funding into this framework.[3] Yet the plan still deviates from it in two ways: (1) charters’ base costs are reduced by 10 percent in three of the four components of the calculation, and (2) their costs are calculated in three components via statewide averages rather than the ratio and salary calculations that apply to districts.[4] Bottom line: Both of these modifications, made without an obvious policy rationale, would reduce the base costs of charters and increase the funding gap between charters and districts.

Second, the base cost model should better reflect the costs of operating high schools. General education charter high schools tend to receive relatively small funding bumps. Some receive estimated increases of less than $500 per pupil—and Dayton Early College Academy, one of the most highly respected urban schools in the state, actually loses $82 per student. This is likely due in part to the base cost model that calls for fewer teachers per student in grades nine through twelve, hence lowering the assumed costs. Such an approach might be okay for entire districts, which can allocate centralized resources to high schools, but it hurts standalone high schools that may actually face higher costs than elementary or middle schools.[5] For instance, high schools may need to purchase expensive science equipment, pay higher salaries to attract teachers, fund more extracurriculars and athletics, or offer college and career counseling. Overall, the base-cost framework may need to be revisited to better reflect the higher costs of a high school education. Of course, that could further inflate the plan’s already hefty price tag.

Third, the Cupp-Patterson plan is mum on the future of the supplemental funding program for quality charter schools that was first implemented in FYs 2020–21. With the backing of Governor DeWine, this $30-million-per-year initiative provides up to an additional $1,750 per economically disadvantaged student to charters that qualify based on academic performance. These dollars help narrow funding gaps, provide extra resources that enable charters to serve more students, and make Ohio a more attractive locale for excellent national charter networks. The plan should include—and make permanent—this valuable charter funding initiative.

Issue 2: Deduction versus direct payment

Instead of deducting dollars designated for charter students from districts’ funding allocations—i.e., the current “pass through” method—the Cupp-Patterson plan would require the state to pay charters directly. This would be a step forward for reasons explained here. The plan, however, lacks one crucial detail. There needs to be clear statutory language that ensures charters are funded through the main, multi-billion-dollar K–12 education appropriation in the state budget, not via a standalone line item that exposes them to budget cuts or even veto. This could be done by simply copying existing statutory language used to fund school districts and joint vocational districts. In sum, any move to direct funding, whether that’s via the Cupp-Patterson plan or otherwise, must ensure that charters are paid through the same pot of money that funds school districts.

Issue 3: The long run

The initial version of the Cupp-Patterson plan called for a periodic updating of districts’ base costs so that their funding levels would adjust with inflation well into the future. The latest version, somewhat surprisingly, scraps the provisions calling for future adjustments of base costs and instead creates a School Funding Oversight Commission that would make recommendations about how to adjust the formula in the years to come. Unfortunately, charters would not be represented on the commission—eight school district officials would be appointed, along with legislators and parents—leaving them devoid of a voice in matters of funding. If such a commission is deemed necessary, charters should have a seat at the table. And speaking of bureaucratic exercises, the revised Cupp-Patterson plan continues to call for a needless study of charter schools’ operating costs. If the plan has captured the cost of educating a typical student—as its developers claim to have done—then that model should apply to charters just the same as districts.

***

Although the revised Cupp-Patterson plan is an improvement from its predecessor, it still doesn’t treat charter schools fairly. Instead, it would exacerbate existing inequities by once again treating charters—despite their superior performance—as second-class public schools. Version three of the plan, should there be one, must right these wrongs.

[1] The “Ohio Eight” refers to Akron, Canton, Cincinnati, Cleveland, Columbus, Dayton, Toledo, and Youngstown.

[2] The updated version of the Cupp-Patterson plan calls for a six-year phase-in of the funding increases, starting in FY 2022. Each year’s phase-in percentage would be determined by future General Assemblies. The phase-in policy for charters and districts would be the same during the six-year period.

[3] E-schools are included in the base cost model. However, continuing current policy, they do not receive several “categorical” funding streams (e.g., extra allocations for economically disadvantaged students). The estimated increases for e-schools under a fully funded Cupp-Patterson plan range from $425 to $1,028 per pupil.

[4] The base-cost calculations in the Cupp-Patterson plan are broken into four components: 1) Teacher, 2) Student Support, 3) Building Leadership and Operations, and 4) District Leadership and Accountability. The 10 percent reduction and statewide averaging apply to the latter three components of charter schools’ base cost calculations. On average, those components make up 42 percent of the overall base cost.

[5] Ohio’s seven STEM public high schools, which are funded much like charter schools, also receive smaller funding increases. Under a fully funded plan, they receive estimated increases of between $302 and $858 per pupil.