A recent article from the Tribune Chronicle in Northeast Ohio covered a school funding analysis published by the personal finance website WalletHub. Several district officials offered comments in response to the analysis, but the spokesperson for Youngstown City Schools directly challenged the study’s data:

Youngstown City School District spokeswoman Denise Dick questioned the per-pupil expenditure numbers provided by WalletHub. Youngstown ranked 52 out of 610 school districts in Ohio. It, according to the report, is the sixth-most equitable district in Trumbull and Mahoning counties.

The district’s per student expenditure is $19,156, according to the report. Dick, however, said the most recent per pupil spending numbers actually are closer to $12,634.

“I don’t think our per-pupil spending has ever been as high as what’s listed in the article,” she said.

The sizeable discrepancy in spending reported by Wallet Hub and cited by Ms. Dick—a roughly $6,500 per pupil difference—certainly raises eyebrows. What gives? The answer is wonky (stick with me!) but important. It also points to the need for a change in the way Ohio reports spending on its school report cards.

First off, the WalletHub data. It relies on U.S. Census Bureau data on K–12 expenditures in districts across the nation, which does indeed report Youngstown’s at $19,156 per pupil for FY 2018. This amount takes into account operational spending—dollars used to pay teachers and staff, buy textbooks, and the like—but excludes capital outlays. The Census Bureau’s technical documentation also makes clear that the agency removes state dollars that “pass through” Ohio school districts and transfer to charter schools, alleviating a concern about federal statistics that has been raised by local school finance expert Howard Fleeter.

While an error is unlikely, it’s worth cross-checking the census data against state statistics. The go-to state source for fiscal data is the Ohio Department of Education’s District Profile Reports, also known as the “Cupp Reports,” which were named long ago after veteran lawmaker and current House Speaker Bob Cupp. Youngstown’s report states that the district spent $18,284 per pupil in FY 2018. That’s not an exact match to WalletHub, but it’s within shouting distance—and far closer than the amount cited by the Youngstown official. Much like the Census Bureau, ODE’s expenditure per pupil data capture operational expenses and exclude capital expenses and dollars that pass through districts to charters.[1]

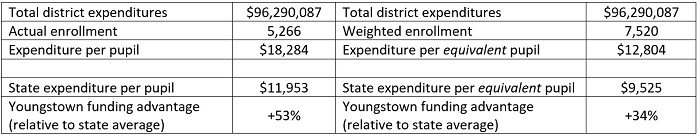

Where then does the $12,634 come from? As it turns out, it comes from the state report card which, lo and behold, tells us that Youngstown spent this sum in FY 2019.[2] But what’s crucial to understand about this source of fiscal data is that, per state law, report cards display an expenditure per equivalent pupil. The basic idea behind this particular statistic is to adjust a district’s actual per pupil expenditures to account for the extra costs associated with educating economically disadvantaged students, English language learners, and students with disabilities. The table below illustrates this methodology using data from Youngstown. The key difference is that the expenditure per equivalent pupil relies on a weighted enrollment—the aforementioned subgroups are effectively counted as more than one student—rather than actual headcounts. In a district such as Youngstown, which serves large numbers of economically disadvantaged students, the weighted enrollment can end up being significantly higher than the actual enrollment.[3]

Table 1: Expenditure calculations for Youngstown City Schools, FY 2018

There are pluses and minuses to the equivalent pupil method of reporting expenditures. On the upside, it creates fairer comparisons of district spending by trying to gauge the amount being spent on a “typical” student. Youngstown’s equivalent amount implies that it spends $12,804 per average student, 34 percent above what the average Ohio district spends on a typical student. This suggests that its spending is somewhat out of line with the state average, though less so than under the actual expenditure calculations. The downside of the equivalent methodology is that it significantly “deflates” the amount of actual spending in districts across Ohio, including Youngstown. This could mislead citizens who are unlikely to think about spending in terms of “equivalent” pupils and who, as surveys indicate, already vastly underestimate the amounts that public schools actually spend.

To clear up the confusion, Ohio lawmakers should require that actual expenditure per pupil amounts be featured prominently on school report cards, just like they are on the Cupp Reports. The equivalent spending data could be maintained as supplemental data, but they must be clearly marked as adjusted amounts that attempt to account for the expenses associated with educating students who usually have greater needs. There should also be an explanation of the methodological differences (including the enrollments used in the denominators), so that users can better distinguish between the two data points.

Productive discussions about school funding—and potential reform of the system—rely on transparent spending data. But as the story from Northeast Ohio reminds us, the wires can get crossed even among people who work in education. By omitting actual spending amounts, the current report card system displays numbers that are out of step with conventional spending data. A more complete presentation of the data is needed to offer a full picture of the resources being dedicated to educate Ohio students.

[1] Unfortunately, the Cupp Report’s per-pupil revenue statistics do not remove funds that transfer to charter schools, thus inflating some district’s revenues. Youngstown’s per-pupil revenues were $25,839 in FY 2018, but that is not an accurate reflection of the dollars received to educate district students.

[2] Youngstown spent $12,804 per equivalent pupil in FY 2018.

[3] In FY 2018, Youngstown reported 100 percent economically disadvantaged students (versus 48 percent statewide), 18 percent students with disabilities (versus 15 percent statewide), and 7 percent English language learners (versus 3 percent statewide).