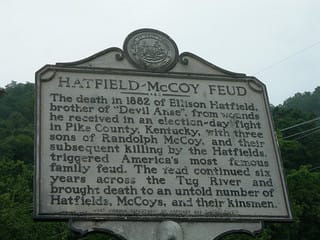

The infamous Hatfield and McCoy feud is an apt analogy for the history of district-charter school relations in Ohio. Neither side has much liked the other for years. Today, however, we see signs that the animosity and acrimony are fading.

The history of Ohio district-charter relations calls to mind legendary feuds. Photo by Jimmy Emerson |

Cleveland Mayor Frank Jackson shepherded legislation through the General Assembly that would, among a host of innovative reforms, provide high-performing charter schools in Cleveland with local levy dollars to support their day-to-day operations. Building on the momentum coming out of Cleveland, Columbus Superintendent Gene Harris put forth a plan that would share local property-tax money with some of that city’s high-flying charters in the form of grants to enable those schools to help boost the performance of low-performing district schools.

There are other Buckeye State examples. Reynoldsburg City School District, serving one of Columbus’s most diverse close-in suburbs, has quietly built a portfolio of school options for its residents over the past decade. Now it is opening those options to students from other districts who might want to attend a Reynoldsburg school. Further, a group of school districts (including Columbus, Reynoldsburg, and the Dayton Public Schools), educational service centers, and the Thomas B. Fordham Foundation have been working together to build a joint charter-school-authorizing effort. While legislation to advance this work has been scuttled twice by the Ohio House (due to furious lobbying by other Ohio authorizers), the partners continue to work together for the benefit of kids across their sponsored schools.

Obviously, not everyone is a fan of charter-district collaboration. There has been much angst expressed about the Cleveland plan by some of the state’s most militant charter supporters and union diehards. Yet Ohio is not alone in the effort to move its charter-district relations forward. In fact, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation has offered $40 million in competitive funding for cities that commit to what they are calling “Charter-District Collaborative Compacts.” So far, such compacts are visible in sixteen cities, including Baltimore, Boston, Central Falls (RI), Chicago, Denver, Hartford, and Los Angeles.

In these communities, neither side is surrendering to the other—or trying to kill it. Rather, according to Gates’s Don Shalvey, both sides are “committed to quality for every student, expanded public school choices and a ‘can do’ spirit that honors teachers and the youngsters they serve.”

Feuds die hard. But for the sake of the kids and grandkids, even the Hatfields and McCoys found peace.

Both charter and district partners also commit to replicating high-performing models of traditional and charter public schools while improving, driving out, or closing down schools that ill-serve students. Decisions are driven by performance as opposed to politics or institutional interests.

In these compact cities, high-performing charters can access district facilities and, in some cases, even local funding. Districts benefit because their academic ratings can increase from the inclusion of test scores from high-flying charter partners. In some compact cities, the partners also commit to working together on such shared challenges as measuring effective teaching and implementing the Common Core.

Feuds die hard. But for the sake of the kids and grandkids, even the Hatfields and McCoys found peace. Children across Ohio (and those in other locales) will benefit if charters and school districts can end their scuffles and find ways to share expertise and resources and otherwise work together to break down barriers to more quality school choices.

A version of this article appeared in the Ohio Gadfly Bi-Weekly newsletter.