NOTE: The Thomas B. Fordham Institute occasionally publishes guest commentaries on its blogs. The views expressed by guest authors do not necessarily reflect those of Fordham.

The release of Ohio’s fall 2020 third-grade test scores last year—the first statewide exams since schools closed at the start of the pandemic—proved sobering, revealing substantial learning losses. At the time, Gov. Mike DeWine described the magnitude of the disruption as a “crisis.”

With an additional pandemic year under our belts, we now have new evidence on how much progress Ohio has made in making up lost ground. In a new report, I analyze the results from the fall 2021 administration of the state’s third grade English language arts assessment. Overall, the scores provide grounds for optimism, but also suggest that the students hit hardest by pandemic learning disruptions also made the least gains through the beginning of the 2021–22 school year.

On the positive front, although third graders started the current school year significantly behind pre-pandemic cohorts, the magnitude of the gap shrank by nearly two-thirds compared to a year earlier. Overall, third grade test scores in fall 2021 were about 0.08 standard deviations lower than the year before the pandemic, corresponding to being behind by between 1 and 1.5 months of learning. For some student subgroups—including English learners and students with disabilities—achievement has largely recovered to the pre-pandemic levels of similar students.

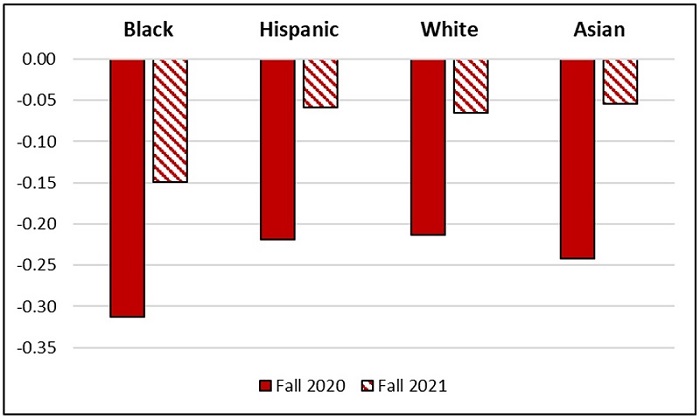

Nevertheless, considerable gaps remain, especially among some of the most disadvantaged populations. Test scores of African American students remained 0.15 standard deviations lower in fall 2021 compared to this group’s pre-pandemic baseline, nearly double the size of the shortfall observed among their white peers. African American students also appear to have made up a smaller share of the initial learning losses, cutting the learning loss by about half compared to at least two-thirds for the other racial and ethnic student groups. In addition, the gap in urban districts remains larger than for other types of school systems.

Figure 1: Achievement losses compared to pre-pandemic cohorts, fall third grade ELA exams

And though all school systems have now largely returned to full-time in-person learning, the previous modes of instruction available to students remain associated with the impact of the pandemic on achievement. Students attending districts that spent most of last year (2020–21) in virtual learning continued to post lower average scores in the fall of the current school year.

These results are largely congruent with those of a recently released national study, which also found much larger learning losses in districts that remained closed to in-person learning for much of 2020–21, along with a growing racial achievement gap.

It is important to keep several important caveats in mind. First, Ohio’s fall exams cover only one grade and subject (third grade reading). As we saw last year, the impacts on spring math scores were generally larger on average than in reading, but the differences between student subgroups were also smaller. Second, the fall exams were completed prior to the Omicron wave in December and January, which resulted in widespread student and teacher absences and disrupted learning substantially for many. In sum, we’ll know more about recovery when spring 2022 test scores are released in the fall.

The results of the fall exams highlight the tremendous energy and resources teachers, school districts, and other public leaders have invested on academic recovery in Ohio—but also the uneven results from these efforts. Apparently due to both teacher and parent opposition, for example, local school districts have largely avoided increasing learning time by extending the school day or school year. Yet this is likely to be the only intervention that can deliver sufficiently large gains at scale and reach the students who need help the most, as Harvard economist Thomas Kane has noted recently.

Instead, districts have pursued a hodgepodge of different strategies and initiatives, offering optional summer programs and after-school tutoring. The problems with such opt-in efforts are two-fold. First, such programming is likely to attract an unrepresentative and unusually motivated group of students and families, potentially risking leaving the most at-risk, disadvantaged students behind. As the former head of Ohio State’s first-year experience program—himself a first-generation college graduate from Appalachia—told me many years ago, students who need additional support the most “don’t do optional.” Second, because motivated students who choose to participate would have probably made especially large learning gains regardless, such services are incredibly difficult to evaluate convincingly. Without credible evidence on what works, we are likely to waste considerable time and public resources on ineffective programming. Yet local districts appear to have largely prioritized exactly these kinds of optional programs in their recovery efforts.

The current school year has also revealed the operational challenges that continue to plague schools across Ohio and disrupt student learning. Many districts struggled with inadequate substitute coverage even before the Omicron wave, and a shortage of bus drivers has made school transportation a particularly acute chokepoint. With labor shortages continuing and new Covid variants combined with waning immunity likely to lead to new surges in the fall and winter, it is essential for all stakeholders and public officials to come together to develop contingency plans now, ahead of the coming year, so that we continue the work of getting Ohio students back on track.

Vladimir Kogan is Associate Professor in The Ohio State University’s Department of Political Science and (by courtesy) the John Glenn College of Public Affairs. The opinions and recommendations presented in this editorial are those of the author and do not necessarily represent policy positions or views of the John Glenn College of Public Affairs, the Department of Political Science, or The Ohio State University.