Almost ten years have passed since Ohio lawmakers enacted early literacy reforms that aim to ensure all children read fluently. Based on pre-pandemic state exam trends, the “third grade reading guarantee” seems to be encouraging a stronger focus on literacy and pushing achievement in the right direction. Yet despite the promising signs of success, policymakers can’t afford to let up. In fact, given the pandemic-related learning losses, they need to double down on the state’s early literacy efforts.

In a recent piece, I examined the retention provision that requires schools to hold back third graders who do not meet reading standards and offer them additional help. While some are clamoring for its removal, doing so would be a huge blunder. By reverting to the disastrous practice of “social promotion,” poor readers would once again be allowed to fall through the cracks. They would pass to fourth grade, and likely beyond, lacking the foundation needed to tackle more challenging material.

But the retention requirement is just one part—albeit a critical one—in the overall package. Several other important policies also comprise Ohio’s early literacy law. This post reviews the guarantee’s diagnostic testing, parental notification, and reading improvement provisions; at the end I’ll suggest some areas for improvement. Note, too, that we’ll cover the intervention requirements for retained third graders in a future installment.

Diagnostic assessments

Under the reading guarantee, schools must assess grade K–3 students annually every fall. In kindergarten, schools may use the language and literacy section of the statewide Kindergarten Readiness Assessment as the diagnostic or administer one of sixteen state-approved vendor assessments. In grades 1–3, schools may fulfill the requirement via vendor or a state-designed diagnostic assessment. These tests gauge whether students are reading on grade level—i.e., on or off track.[1]

The diagnostic is a necessary screening tool that encourages timely intervention, even prior to third grade. But we ought to ask whether these tests are accurately identifying struggling readers. Remember, there’s no single statewide diagnostic test, so schools could be choosing assessments that are weakly aligned with state reading standards and risk overlooking children who need extra help.

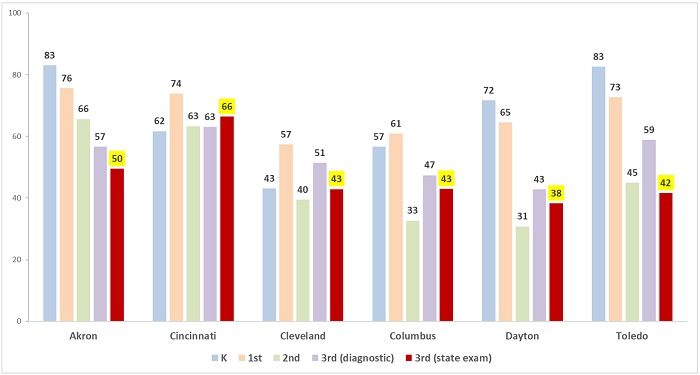

When examining pre-pandemic data, there is some reason for concern. Consider figure 1, which displays K–3 on-track percentages in Ohio’s largest urban districts and their third grade proficiency rates. In four districts—Akron, Columbus, Dayton, and Toledo—the on-track percentages in grades K–1 are noticeably higher than their third grade reading proficiency rates, by about 15 to 40 percentage points. Then they fall significantly in second grade, and by third grade they track more closely to proficiency rates. This may indicate that the kindergarten and first grade assessments in these districts are giving a faulty assurance that students are on track when they really are not.

Figure 1: Grades K–3 “on-track” percentages in reading (fall 2019) versus third grade ELA proficiency rates (spring 2019), selected districts

Source: Ohio Department of Education, 2019–20 K–4 literacy report and 2018–19 district achievement data.

Irregular data are not limited to these districts. In fact, some Ohio districts reported all or virtually all of their children as on track in reading, yet had low third grade proficiency rates. For instance, Waverly and Paulding school districts posted 100 percent on-track rates in all grades K–3 on fall 2019 diagnostics, but had third grade proficiency rates of 63 and 76 percent, respectively. There are some oddities in the other direction, too. Wooster and Copley-Fairlawn, for example, reported that less than 10 percent of grades K–3 students were on track, but their third grade proficiency rates were 75 and 90 percent in spring 2019.

Overall, there’s enough inconsistency in the data to question whether the diagnostic tests are accurately identifying students as being on or off track. Are some districts using tests that yield “false negatives”—failing to identify a reading deficiency when one exists? Conversely, are other tests more prone to “false positives”? Accurate diagnostic tests are crucial, as those results drive decisions about whether students receive extra reading supports.

Parental notification and improvement plans

Under statute, a school district must do two things when children are deemed off track via reading diagnostics:

- Notify student’s parents or guardians. By written notification, districts must report the reading deficiency, describe the current services provided to the student, propose instructional supports designed to remediate the deficiency, and disclose the possibility of retention after third grade.

- Create a reading improvement and monitoring plan. Within sixty days of receiving an off-track result, the district, with input from a student’s parents and teachers, must develop an improvement plan. Among a few other items, the plan must identify the specific reading deficiencies, outline the supports needed to remedy them, create a monitoring process to ensure students receive such supports, provide parents with opportunities for involvement, and offer a reading curriculum that “assists students to read at grade level.”

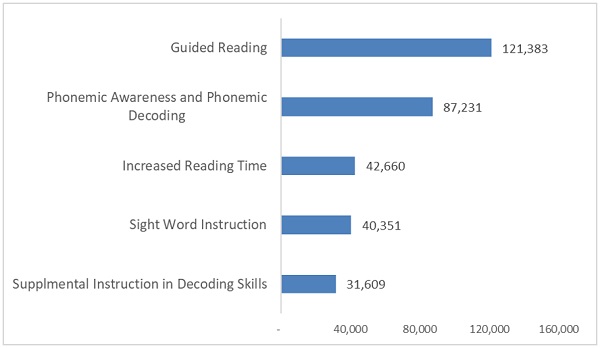

Per state law, the Ohio Department of Education (ODE) reports the types of interventions that students with an improvement plan receive. Figure 2 displays the five most frequently reported interventions for the 2020–21 school year (the numbers are mostly similar to 2019–20). What’s noticeable are the broad intervention categories. For example, what exactly happened during “increased reading time”?

Figure 2: Most frequently reported interventions for off-track readers, 2020–21

Source: Ohio Department of Education

To its credit, ODE has recently overhauled this reporting system, so that schools must now report literacy interventions with greater specificity. Gone are ambiguous terms, and instead, schools will now report using categories such as “explicit intervention in phonemic awareness” and “explicit intervention in vocabulary,” terms that appear to be well-defined by ODE and are referenced in its statewide literacy plan. The new list does include a few highly questionable but, unfortunately, still-used approaches, though ODE flags those as not being part of its literacy plan (e.g., the three cuing system). Moving forward, this change is a step forward in transparency and should yield a clearer picture of schools’ efforts to address reading deficiencies in the early grades.

Policy refinements

The diagnostic testing requirement, along with mandatory parental notification and improvement plans for off-track readers, are core strengths that should remain firmly in place. Yet policymakers could also consider fine-tuning these policies to better ensure they are being well-implemented. Here are five ideas that would strengthen these provisions.

- Disapprove a diagnostic test if it’s not accurately identifying off-track readers. The on/off-track data raise the possibility that some assessments overlook struggling readers. To ensure accuracy, lawmakers should require ODE, before approving a vendor’s test, to demonstrate its alignment with state reading standards and include documentation that the on-track target matches the rigor of Ohio’s proficiency standard. If such an analysis does not demonstrate alignment, it should be disapproved. The analyses should be made public, much like those behind the ACT-SAT concordances.

- Confirm that parents are notified and involved in the development of their child’s improvement plan. Because parental involvement is so crucial to a child’s ability to read, schools need to engage parents when a child is struggling. While there isn’t evidence that schools are dropping the ball, there is also no indication that ODE monitors compliance with these parental requirements. To ensure this occurs, legislators should require ODE to conduct random audits that check whether districts are notifying and involving parents.

- Offer parents guidance and resources to help their child become a better reader. There is no one more interested in a child becoming a good reader than his or her parents. That being said, some parents may not have a clear understanding of how they can best support their child’s progress. One opportunity to provide more information is through the written notification. Legislators could require ODE to develop—with the input of parents, researchers, and educators—a standard document appended to the notification, which offers general advice and resources that help parents engage in the improvement process.

- Ensure that the reading curriculum used to instruct off-track students aligns with the science of reading. As noted above, state law currently requires an improvement plan to use a reading curriculum that “assists students to read at grade level.” That language is overly vague. Lawmakers should strengthen it by insisting that any curriculum aligns with the science of reading, a term that refers to literacy practices backed by a strong body of evidence.[2] Following Colorado’s footsteps, Ohio lawmakers could go a step further and create a state-level advisory committee that approves early literacy curricula; only those aligned with this science would be allowed for use in improvement plans.

- Require periodic evaluations about the effectiveness of reading interventions. To date, there has been no rigorous evaluation of the third grade reading guarantee, either as a whole or its component parts. That should change. As a good first step, ODE’s revised reporting system should yield higher quality data on interventions, which could then be linked to student outcomes. But without a legislative mandate for evaluation[3] or money set-aside to undertake one, this type of analysis isn’t likely to happen. That’s a loss for educators and parents, who would benefit from research that pinpoints which remedies work best for which deficiencies.

The ability to read fluently is crucial to lifelong success. The third grade reading guarantee has the right goals, and the policy building blocks are in place to make certain that children acquire foundational reading skills. But to truly fulfill its promise of being a “guarantee,” lawmakers need to further strengthen these policies to ensure that all struggling readers in grades K–3 receive the extra help and support they need.

[1] The fall diagnostic tests gauge reading achievement against a student’s previous grade standards. For example, a fall second grade test measures performance against first grade standards. The fall version of the state ELA exam cannot be used as the third grade fall diagnostic test (the state exam is given about a month later).

[2] While not, to my knowledge, used in Ohio law, the term is used in Colorado’s early literacy law and is key to ODE’s statewide literacy plan.

[3] There is language directing ODE to annually report “if available, an evaluation of the efficacy of the intervention services provided.” In its last two annual reports—the only ones posted online—ODE notes that it could not undertake an evaluation due to data limitations.