The Ohio House recently passed its version of the state budget (HB 110) for FYs 2022–23. The headline for K–12 education was the inclusion of the Cupp-Patterson school funding plan into its budget bill (as most observers expected). If enacted, this proposal would overhaul Ohio’s school funding formula and—when fully implemented—add an additional $2 billion per year in state outlays for K–12 education. Beyond the headline, the House budget contains a slew of policy details—including a couple small steps forward, a few head-scratchers, and some bad ideas, too.

Baby steps forward

Creates a “direct funding” model for choice options. In line with the original Cupp-Patterson plan, the House budget moves public charter and STEM schools along with private-school vouchers to a direct funding model. Although this shift doesn’t affect the funding levels for choice students, the transition could alleviate tensions around the current “pass through” approach whereby money designated for these students is subtracted from their home districts’ state aid. Direct funding, however, needs to be done with extreme care to insulate choice programs from future budget reductions or even line-item vetoes. On this count, HB 110 isn’t quite there. The income-based EdChoice program is listed as a standalone item, making it vulnerable to cuts in the future. Charters, STEM schools, and the other voucher programs are funded via the main education appropriation, but these options could still be exposed to a line-item veto under HB 110. Though unlikely to occur under Governor DeWine, choice programs could be targeted in future budgets if the House approach to direct funding is adopted.

Eliminates a proposed 10 percent reduction to charter and STEM schools’ base cost. For no apparent reason, an earlier iteration of the Cupp-Patterson plan calculated charter and STEM schools’ base costs at lower levels than districts. Fortunately, HB 110 corrects this glaring inequity by eliminating this reduction. However, HB 110 retains another inequitable policy within the proposed funding framework that denies charters and STEMs a minimum number of special teachers (e.g., art or physical education) and student support staff. The absence of these minimums—which apply for districts—decreases funding for charter and STEM schools by hundreds of dollars per pupil, again with no clear policy rationale.

The head-scratchers

Increases economically disadvantaged funding but at the expense of the Student Wellness program. From the outset, the Cupp-Patterson plan has called for an increase in the “categorical” funding stream based on economically disadvantaged (ED) enrollments. That’s a good thing, and HB 110 incorporates this increase. But the legislation finances it by using dollars budgeted for the Student Wellness and Success Fund (SWSF), a new-ish program championed by Governor DeWine that aims to support students’ social-emotional and mental health needs. The House explained the decision by saying that it streamlines duplicative programs. There is some truth to that, as both programs generally direct more money to high-poverty schools. Still, the move is puzzling. It was always expected that the increase in ED funding was going to improve the equity of the system because the Cupp-Patterson plan never proposed raiding another “progressively” structured funding stream to pay for it. But the way HB 110 funds the ED increase seems to simply maintain the status quo, robbing Peter to pay Paul. How does that help low-income kids?

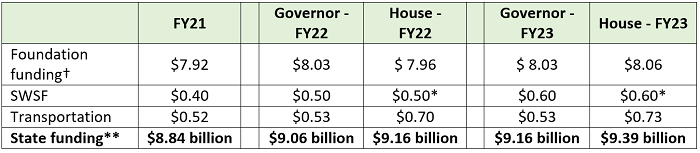

Leaves tough decisions about fully funding the Cupp-Patterson plan to future leaders. Given all the excitement about the funding bump proposed in the Cupp-Patterson plan, the House budget calls for generally modest increases in education spending. Table 1 displays education funding in the current year (FY 2021) and the amounts proposed by Governor DeWine and the House for the next biennium. Relative to the Governor’s plan, the House raises state education funding by roughly $100 million in FY 2022 and $230 million in FY 2023.

Table 1: An overview of state education funding, current and proposed (in billions)

*In the House plan, the Student Wellness and Success Funds remain a standalone line item, but are used primarily to fund an increase in the economically-disadvantaged component of the funding formula. **This excludes federal and local dollars, various smaller state expenditures (e.g., educator licensing and assessments), and money for K–12 education not funded via ODE budget (e.g., school construction dollars and property tax reimbursements). † This includes the additional $115 million that was included in the omnibus amendment to the House budget.

The reason why the House funding increases fall short of the promised $2 billion in added spending is due to HB 110’s six-year phase-in of the Cupp-Patterson plan. While this gradual approach may have been necessary given budget constraints and was part of a legislative version introduced in the last General Assembly, it continues to raise questions about how the rest of the plan will be paid for, especially now that the House has soaked up the SWSF funding. Are they leaving the heavy lifting—possibly raising taxes—to future lawmakers? Will they decline to fund it or choose to start over? In the end, it remains a mystery why House lawmakers would champion an education funding plan without offering a concrete roadmap for covering its costs.

Steps backward

Cuts funding for the quality charter schools program. Back in 2019, Ohio enacted a first-of-its-kind program that provides much-needed extra funding for high-performing charter schools. These supplemental funds help to narrow chronic funding gaps, build the capacity of successful schools to serve more kids, and incentivize continued improvement in sector performance. In the first two years of the program, about a quarter of Ohio charters received these funds. However, as more schools qualified in year two, the per-pupil funding amounts dropped to fit the program’s fixed appropriation. Rather than receiving the full $1,750 per economically disadvantaged student, qualifying schools received just $1,023. To better align the funding amounts, Governor DeWine proposed increasing the program appropriation to $54 million per year. Unfortunately, the House cut that amount to $30 million. Unless the Senate reverses course, this will underfund the program and deny high-performing charters critical resources needed to serve more students.

Slashes funding for interdistrict open enrollment. More than 80,000 Ohio students attend school in a neighboring district through the state’s interdistrict open enrollment program. Under current policy, the state funds these students at the full “base amount” of $6,020 per pupil. But as discussed in more detail here, the Cupp-Patterson plan drastically reduces these per-pupil amounts for open enrollees. Unfortunately, HB 110 does not address this problem. If the plan is enacted without a fix, thousands of open enrollees may find themselves shut out of the schools they currently attend, as districts decide that it no longer makes economic sense to enroll non-resident students.

Allows opt-outs of college-entrance exams. The last glaring problem with HB 110 is its introduction of an opt-out provision to the universal administration of ACT or SAT exams to high school juniors. Starting with the class of 2018, this policy has ensured that all young people have at least one opportunity to take these assessments. Previously, less than half of many districts’ graduates took these exams. In Lorain, for example, just 16 percent of its classes of 2016 and 2017 took the ACT or SAT. In Lima, it was a mere 36 percent. How many students who skipped these tests could’ve gone on to competitive colleges? We’ll never know because—at that time—no one required them to take an entrance exam. Sadly, the House makes a change that could reduce the number of students taking college-entrance exams and inadvertently close doors to higher education for some talented young Ohioans.

* * *

K–12 education policy should focus on unlocking great educational opportunities for all Ohio students. Overall, it’s difficult to see how the House budget furthers that goal. The chamber’s signature school funding plan is left dangling in the wind. Charter schools—even the best ones in the state—will continue to suffer from inequitable funding. Interdistrict open enrollment will be gutted. Even funding for low-income students is barely improved, if at all, under HB 110. Thankfully, the House isn’t the last stop. With any luck, the upper chamber will take a different approach, one that puts Ohio students at the heart of education policy.