Nestled within the General Assembly’s final budget plan as sent to Governor Kasich on June 28 was an under-the-radar provision that would have eliminated Ohio’s teacher residency program. This didn’t get a lot of coverage. Neither did Governor Kasich’s veto, which saved the program.

The limited coverage was likely a symptom of unfamiliarity: Unless you have direct contact with this program, you probably don’t know much about it. Yet the legislative change would have had a significant impact on the experiences of new Ohio teachers. Let’s examine what the residency program is and why the General Assembly should look to fix it rather than continue to seek its elimination.

Background

Back in 2009, Governor Ted Strickland’s education reform and funding plan proposed both a teacher residency program and a licensure ladder to ensure that only “top-quality” teachers would stand in front of Ohio pupils. In response, lawmakers created a residency program based on the idea that new teachers need robust support and training and that far too many schools were leaving their newbies to sink or swim.

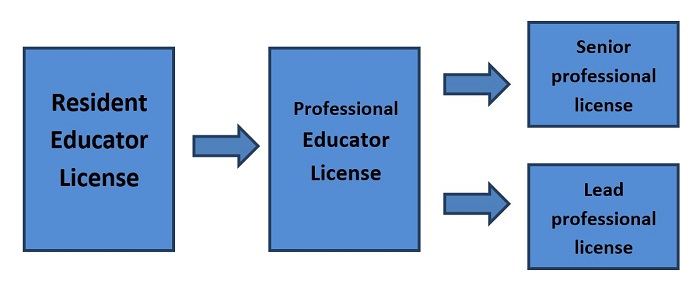

Ohio now implements a ladder licensure system with an embedded residency program. In general, the licensure system looks like this:[1]

As the diagram indicates, all new teachers begin with the Resident Educator License. To receive one of these, a would-be teacher must meet a variety of requirements, including earning a bachelor’s degree and passing various licensure tests. Once issued, the license covers a four-year period and serves as the stepping stone to the advanced licenses.

During that four-year period, teachers are required to take part in the Resident Educator Program (REP), which was designed to provide support through mentorship, collaboration with veteran educators, professional development, and formative assessment feedback. Program completion requires successfully passing the Resident Educator Summative Assessment (RESA), a performance-based assessment that requires teachers to electronically submit a portfolio of completed tasks that demonstrates their teaching abilities. RESA submissions are graded based on a rubric that is aligned to the state’s Standards for the Teaching Profession.

Although the resident license is technically renewable, it is not intended to be permanent. Teachers are only able to renew or extend it if they need more time to complete the REP or RESA. In other words, in order to progress to a professional license—and continue teaching in Ohio—educators must complete the residency program and pass the assessment.

Program pushback

Despite the good intentions of policymakers, on-the-ground feedback has been mixed. On the one hand, some educators have expressed concern about needless paperwork and the program’s rehashing of material that’s already been covered in teacher education programs. On the other hand, there are quite a few Ohio teacher education programs that aren't doing a good enough job—and some Ohio educators have said that the program helps to inculcate and reinforce effective teaching habits.

The greatest pushback has been against RESA assessment. It’s been accused of failing to provide immediate, direct, and specific feedback on practices and being too cumbersome when piled on top of a teacher’s typical workload. One Ohio educator called RESA “the worst experience I’ve had since becoming a teacher.” There’s even a Change.org petition to end it. According to news reports, complaints like these are exactly why the House proposed eliminating the program all together.

But when the REP was put on the chopping block, quite a few influential folks stood up to defend it. A REP coordinator from Solon City Schools—one of the highest performing districts in the state—told lawmakers that the mentoring aspect of the program, combined with the accountability of RESA, ensures that “all students will have a competent teacher.” Both state teachers unions voiced their views on the importance of maintaining support networks for new teachers. And State Superintendent Paolo DeMaria shared that he was worried about the “gaping void” that removing the program would create—without it, any Ohio teacher who teaches for four years under a resident license or alternative resident license is automatically qualified to apply for a permanent professional license.

Moving forward

Kasich’s veto allowed the residency program and its assessment to live another day, and that’s a good thing. As the Governor notes in his veto message, the rationale for the program still stands: New teachers do need extra help, and providing them with it is “critical for student success and for retaining teachers.” Furthermore, without a policy in place, there’s no guarantee that districts will give them the requisite support. Other states with high-performing education sectors (like Massachusetts) have effectively leveraged rigorous licensure systems (and other critical reforms) to increase student performance. A recent study demonstrated that high-quality mentoring and induction programs can also raise student achievement. While Ohio’s program hasn’t been put through a similarly rigorous review (one would certainly be welcome, though), its structure and requirements match the framework of other programs and systems that have had positive impacts.

But REP and RESA critics also have legitimate concerns. DeMaria acknowledged as much when he said that the Ohio Department of Education (ODE) “would like to have the opportunity to address issues within the system, rather than see it eliminated.” There are already some changes in the works, including allowing newly licensed teachers to “test out” of the program. That’s a good start. Two additional revisions should be considered:

Align the RESA and Ohio Teacher Evaluation System (OTES) rubrics. It’s no secret that Ohio’s teacher evaluation system needs work. The state’s Educator Standards Board released some solid recommendations for an overhaul in March. One of these suggestions is to revise the rubric that evaluators use during classroom observations. RESA submissions—which include videos of educators teaching lessons—are also evaluated on a rubric. This gives the General Assembly an opportunity to declare that the same rubric should be used for both the evaluation system and the licensure system.

From a practical standpoint, it would be easier for new teachers to have one observational rubric to model their practice on instead of two. But such a move toward alignment (and common training for both OTES and RESA evaluators) would also address another common criticism, which is that teachers who score well on one rubric sometimes fail to do so on the other. If Ohio is serious about having rigorous evaluation and licensure systems, policymakers should consider aligning the two so that teachers are held to the same standards throughout their careers.

Improve the feedback loop. A common criticism of RESA is that it doesn’t offer teachers actionable insight into why they pass or fail certain portions of the assessment or how to improve their practice moving forward. To be clear, RESA was only intended to be a summative assessment that determined teacher ability prior to permitting them to move on to a more advanced license. But considering how much time teachers put into their online portfolios—and the dearth of quality professional development experiences that many subsequently experience—it’s reasonable for them to request some final constructive criticism. ODE could consider asking Educopia—the organization responsible for RESA’s creation and implementation—to improve the nature of their feedback by giving participants clear examples of what they do well and what they need to improve on.

In the end, this is yet another policy that policymakers would be wise to mend rather than end. After all, we went down this road for a reason—too few beginning teachers were ready for the rigors of teaching, and the sink or swim mentality only compounded the issue. The Resident Educator Program is a framework with promise, and it can be tweaked to live up to its potential.