In December, the Ohio Auditor of State released a special audit of the State Teachers Retirement System (STRS). The audit was conducted after a report commissioned by the Ohio Retired Teachers Association (ORTA) raised a number of concerns about the system that manages the pensions of current and retired teachers, the vast majority of whom are enrolled in a traditional “defined benefit” plan. The auditor reviewed STRS’s operations, and found “no evidence of fraud, illegal acts, or data manipulation.” That’s a relief, but it shouldn’t be reason for celebration.

The report touches on several worrying—though not unlawful—issues with the system’s structure, including the following:

Enormous unfunded liabilities. This, of course, isn’t a new or unknown problem with STRS and many other public pension systems. But it’s worth noting once again the enormity of STRS’s liability—the value of its assets versus the value of the retirement benefits promised to teachers with a DB pension plan. The auditor reports that, as of the end of June 2022, STRS had $83 billion in assets on hand but had racked up $105 billion in retirement liabilities. That results in a staggering $22 billion unfunded liability. Such a mountain of debt in a pension fund is of concern, as it could result in either benefit cuts or increased contributions into the fund from school districts and teachers. These are very real possibilities. On the benefits side, retirees have been understandably upset about the lack of cost-of-living adjustments (COLA) to their benefits in an age of sky-high inflation (a small, one-time 3 percent COLA was finally given last year after lengthy agitation). Had the system been in a better financial position, STRS may not have needed to suspend COLAs in 2017 after many years of granting them. And last fall, reports emerged that STRS was planning to petition lawmakers to increase the rate school districts pay into the pension fund, which is currently 14 percent of teacher payroll. If that goes through, schools will either have to reduce their current spending on education, or they’ll need to ask citizens to approve higher local tax rates to cover the increased retirement costs.

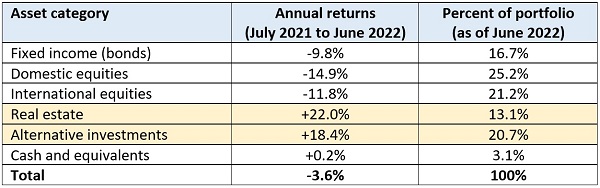

Transparency around STRS’s alternative investments. Due to the nature of the concerns raised in the ORTA report, the auditor’s report spends a lot time discussing this part of the system’s portfolio. It’s important to remember that STRS isn’t your average investor. Not only does STRS invest in traditional stocks and bonds, it also puts billions into alternative investments such as real estate, private equity, hedge funds, and commodities. As of June 2022, STRS held approximately $30 billion in such alternatives. It wasn’t always this way: Following national trends, STRS has increased its allocation to alternatives (including both real estate and other non-traditional investments) from just 14 percent in 2001 to 34 percent in 2022. As the table below indicates, STRS’s alternatives—at least in FY 2022—delivered strong returns that outpaced stocks and bonds. Yet from 2016 to 2021, the auditor notes that STRS’s alternatives (excluding real estate) underperformed the broader stock market, returning 14.5 percent per year versus 18.0 percent for the Russell 3000 index.

Table 1: STRS’s investment returns and asset allocations

The auditor’s report focuses on transparency challenges that come with alternatives—particularly private equity—something other analysts have discussed, as well. One issue is the opaque and perhaps exorbitant fees that private equity firms may be charging STRS (excluding real estate, most of its alternatives are in private equity). Because these agreements are deemed “trade secrets,” there is little way of knowing what fees STRS is paying, which can take a bite out of investment returns. The other issue raised by the auditor is the uncertain valuations of alternatives. Unlike publicly traded stocks, whose prices are transparent, the values of alternatives are more opaque and subjective. The auditor writes: “Determining real estate and private equity fund investments’ fair values…requires subjective, potentially biased valuations.” While the report notes external checks on valuing these investments, there is no way of knowing how much those assets are truly worth until they are sold. That should leave us less easy about the precise value of STRS’s assets at any given time.

Staff bonuses. Over the past year, another thing that has infuriated retired teachers is the decision by STRS to award $10 million in bonuses for system staff. The auditor didn’t find anything unlawful about the way STRS provided the extra pay. But one should ask what STRS was thinking when it doled out millions in extra compensation during a down year for the system’s investments, and when retirees were being asked to stretch their benefits without an adequate COLA. Administrators might say that this compensation structure, which already includes relatively high base salaries ($200,000 plus for some managerial level positions), helps retain highly-skilled investment professionals. But it’s always possible that the system could fare just as well with a more traditional investment strategy that doesn’t require expensive technical expertise.

* * *

The state auditor concludes by offering several recommendations that would add more sunlight to the system. That would be welcome. But Ohio needs to do more than just nibble around the edges. It’s past time for the state to let go of its archaic “defined benefit” plan with its massive unfunded liabilities, the regular fiddling with teachers’ retirement benefits and contribution rates, opaque investments, and ill treatment of teachers who choose not stay in an Ohio classroom for their entire career. Instead, Ohio should transition teachers (new hires) to 401(k)-style “defined contribution” plans that most businesses and a few states now make their primary retirement plan (STRS offers a DC option, but it’s not the default and few enroll in it). From the state’s perspective, this approach would be easier and less costly to manage and wouldn’t accrue any unfunded liability. It might also make teachers less suspicious about the “system,” and would even make them wealthier in retirement. What’s not to like about that?