With a federally-induced “fiscal cliff” looming and enrollments on the decline, school district leaders need to find ways to tighten their belts and operate within their means. One way to do that is by permanently closing schools that are low-performing and under-enrolled. Academic measures indicate that such schools are ineffectively educating students, while half-empty classrooms are another red flag that something is going wrong. Studies from various locales (including Ohio) find that students are usually better off when low-performing schools close and they subsequent enroll elsewhere.

On top of that, continuing to operate under-enrolled schools can be a financial drain. Districts spend millions to maintain under-utilized facilities, run additional bus routes to and from the school, and incur other avoidable costs. While permanent closure is often a sad process, it can lead to positive outcomes for all involved. Districts carve out room in their budgets—perhaps allowing them to avoid staff or pay reductions—while students benefit by moving to higher-performing schools.

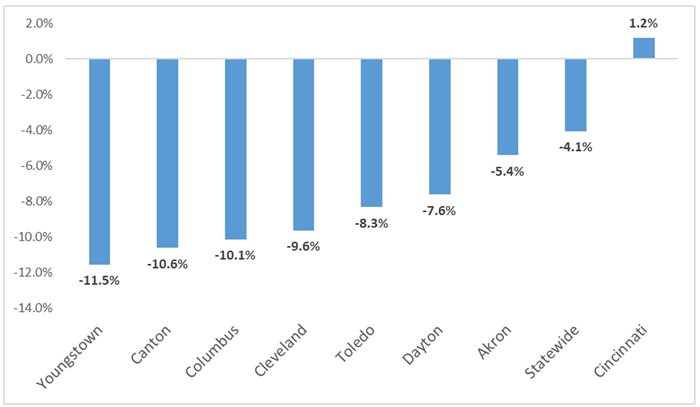

The leaders of Ohio’s large urban districts should especially consider permanent closures. Historically, they’ve operated many of the state’s lowest-performing schools, and as figure 1 indicates, all of the Ohio Eight urban districts (save for Cincinnati) have suffered enrollment declines in recent years. Headcounts in Cleveland and Columbus slid by 10 percent between 2017–18 and 2022–23; the losses were even bigger in Canton and Youngstown. This means that the Ohio Eight districts are likely to have under-enrolled schools. And because of their larger size, they should also have other schools that can accept students displaced by a closure.

Figure 1: Percent change in enrollment in the Ohio Eight districts, 2017–18 to 2022–23

Several other mid-sized school districts are in the same boat as the Ohio Eight. For instance, Lakewood, Willoughby-Eastlake, and Hamilton all experienced enrollment declines of just over 10 percent between 2017–18 and 2022–23, while Parma, Lorain, and Springfield (Clark County) lost 8 to 10 percent. Districts such as these should also consider closing schools as their enrollments wane and budgetary right-sizing becomes a necessity.

As district leaders grapple with which schools to shut, they should take various factors into consideration, including the physical condition of the building and the alternatives for displaced students. But as a starting point, they should first identify the lowest-performing schools in their district as candidates for closure. In so doing, they should focus on two key report card measures: the state’s achievement and progress ratings. The achievement rating is based on the performance index, a composite measure of student proficiency on all state assessments, while the progress rating is based on value-added calculations that gauge student academic growth over time on state exams. Low ratings—one or two stars—on both components indicate that students have significant academic deficiencies and make little year-to-year growth that would help them catch up. In sum, these are ineffective schools where students fall behind and remain that way.

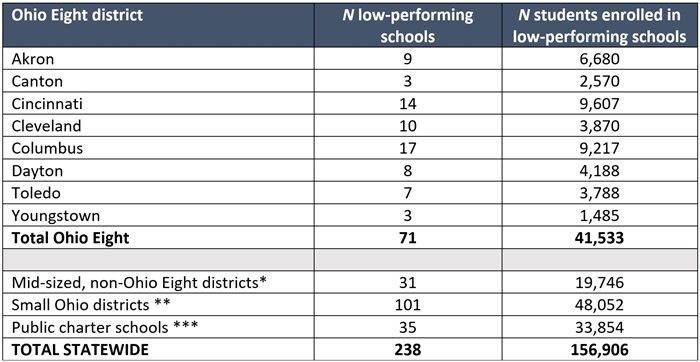

As Table 1 shows, hundreds of schools across the state struggle on both of these academic indicators. In the Ohio Eight, seventy-one schools (out of 421 total) received one- or two-star achievement and progress ratings in both of the past two years. Outside of the Ohio Eight, thirty-one schools run by mid-sized districts—districts such as Lorain or Springfield—met these low-performing criteria. Just over 100 low-performing schools were run by smaller districts, and thirty-five are public charter schools. Taken together, these 238 underperforming schools enroll just over 150,000 students, or roughly one in ten statewide.

Table 1: Low-performing schools in the Ohio Eight districts and statewide

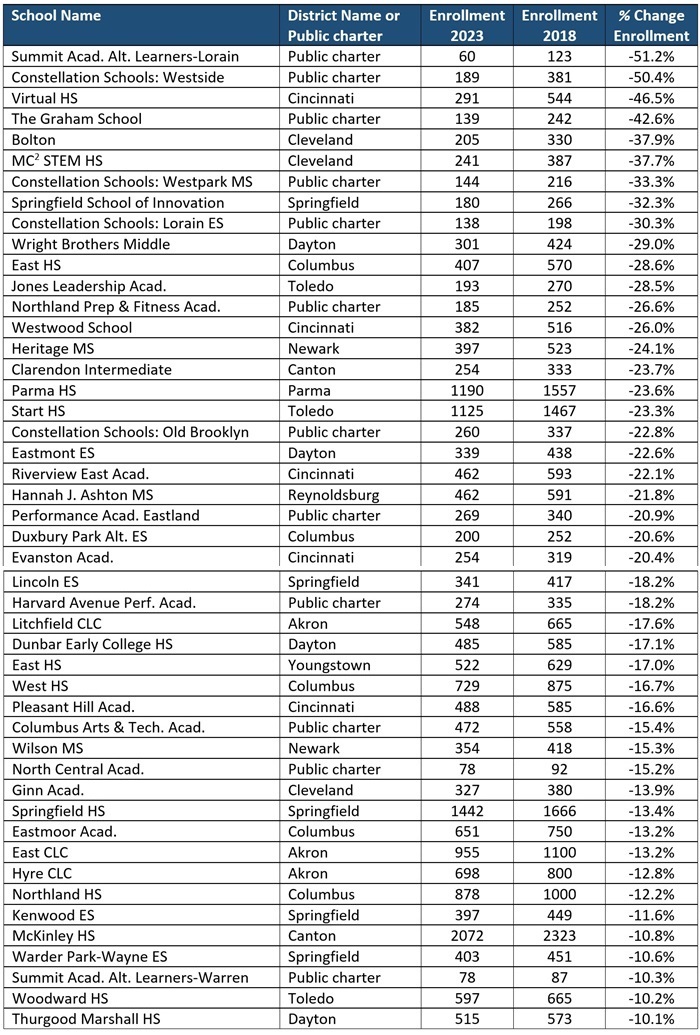

Of course, low-performing schools are not necessarily under-enrolled. Local officials likely have access to data about a particular school’s enrollment relative to its physical capacity (perhaps in facility planning documents or occupancy certificates). Unfortunately, capacity numbers are not reported statewide. So as a rough proxy, I consider schools as under-enrolled whose headcounts have declined by more than 10 percent between 2017–18 and 2022–23. By my count,[1] there are forty-seven low-performing, under-enrolled schools run by a mid- to large-size district or a public charter school. To their credit, charter sponsors—the oversight entities with authority to close charter schools—have in recent years permanently closed more than 100 low-performing charters. But they, too, need to remain vigilant about quality and close the chronically low-performing schools in their portfolios.

Table 2: Under-enrolled, low-performing schools in mid- to large-sized Ohio districts, and charters

* * *

Many Ohio school districts are serving fewer students, and some of them they face financial challenges that necessitate more efficient operations. Permanently closing low-performing schools—and transitioning students to better ones—should be a tool that districts use to move achievement in the right direction while also stretching the school dollar. It’s never easy to permanently close schools, but when done thoughtfully and strategically, district leaders can better serve students and communities.

[1] This would underestimate the number of under-enrolled schools if 2018 enrollments were already below a school’s physical capacity.