For decades, analysts have observed large achievement gaps between low-income children and their peers, disparities that have only widened due to Covid. To address these gaps, there is universal agreement that low-income students require additional resources to support their education. To its credit, Ohio has long provided additional state funding to public schools that serve more economically disadvantaged students. This year, for example, the state will send Ohio schools roughly $450 million in supplemental dollars through a funding stream known as DPIA, or “disadvantaged pupil impact aid.” DPIA will increase in FY 2023—and beyond, if lawmakers continue phasing-in the state’s new funding model.

Providing extra dollars for low-income students is important, but how schools spend those funds also matters greatly. As Eric Hanushek of Stanford University told Ohio lawmakers last year, “How money is spent is more important than how much is spent.” His claim is backed by numerous studies indicating that some interventions, programs, and educational “inputs” deliver more bang for the buck. The most obvious example is teacher quality, where studies find that their “value-added”—i.e., their contributions to student achievement—vary widely from teacher to teacher. Thus, dollars spent to retain high-performers are being used more productively than dollars spent on low-performers—or increases that go to everyone, indiscriminately. Another example is tutoring. Whereas “high-dosage” tutoring raises pupil achievement, poorly designed tutoring programs have proven to be ineffectual.

So are Ohio schools spending funds wisely? A recent report from the Ohio Department of Education (ODE) offers some insight, at least with respect to DPIA funding. But the report’s data—and the lack thereof—also raises questions about the state’s approach to this important program. It’s clear that Ohio could be doing more to ensure that DPIA dollars are used to improve the outcomes of economically disadvantaged students.

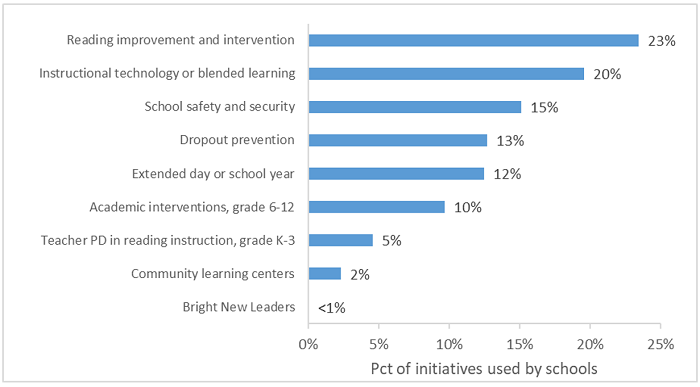

First consider the chart below, which displays the key data point presented in the ODE report. The figure shows a breakdown of initiatives that schools undertook with DPIA funds. The most common usage was reading improvement and intervention (23 percent of the initiatives reported by Ohio schools), with IT and blended learning coming in a close second. The least used options were creating community learning centers or hiring a principal trained through the Bright New Leaders program.

Figure 1: How Ohio schools used DPIA funds in fiscal years (FYs) 2020 and 2021

Source: Ohio Department of Education.

A few observations:

- For FYs 2020–21, state law enumerated nine permissible uses for spending DPIA funds.[1] Most of these categories are loosely defined—Figure 1 reflects statutory language almost verbatim—and thus allow for a large variety of activities. In fact, ODE notes that under the “reading improvement and intervention” option, schools used money to hire reading coaches and intervention specialists, offer tutoring programs, purchase textbooks and curriculum, and pay for teacher professional development. Similar ambiguities would apply in categories like “dropout prevention” or “academic interventions in grades 6–12.”

- A sizeable portion of DPIA initiatives were related to IT or blended learning and school security. Though not unimportant—and perhaps a good use of general foundation or federal dollars—one might question whether the state should promote basic IT and security measures as high-priority strategies to move the academic needle for low-income students.

- There remain big unanswered questions. We aren’t told what proportion of DPIA funds made their way to the schools that low-income students attended as opposed to other schools within the district. We can’t tell whether these initiatives were geared to the needs of disadvantaged children or open to the general population. Nor do we have a sense of the quality of the initiatives. Most important, no one has a clue whether DPIA dollars—and the activities they supported—drove higher student learning.

As it currently stands, the spending policies for DPIA are a mush. On the one hand, the spending requirements are too vague to encourage initiatives that studies suggest have the most impact on student learning. Yet at the same time, they might also be overly restrictive. The categories could be pushing schools into spending on mundane activities such as professional development or basic goods like Chromebooks and computer software, while limiting more creative or better uses of these resources. Taken together, there seems to be lack of clear expectations and accountability measures that ensure these funds are used to better the outcomes of Ohio’s low-income students.

Ohio lawmakers should change their approach to DPIA. (Note, they also need to address problems with the enrollment data used to allocate these funds to better target DPIA funds.) In my view, legislators could pursue one of two options.

Option 1: Get strategic and specific about DPIA spending uses. Under this approach, the legislature—likely with expert advice—would set forth a limited number of specific uses of these funds. Only initiatives that have clearly demonstrated effectiveness would be included. This option, however, would place greater constraints on schools’ spending alternatives, such as discouraging them from combining DPIA dollars with other funding streams in efforts to create a more comprehensive spending strategy. The option could easily open debates about which practices are most effective and worthy of inclusion. That being said, by requiring schools to use funds on only proven practices, it holds potential to improve student outcomes. The following list offers an idea of what categories might be included as approved spending uses:

- Implementing high-dosage tutoring

- Hiring teacher coaches to improve classroom practices

- Adopting early literacy programs that align with the science of reading

- Increasing the pay of highly effective teachers

- Double-dosing algebra courses

- Expanding access to AP/IB courses, and high-demand industry credentialing programs

Option 2: Provide maximum flexibility but demand more rigorous oversight and accountability. Another approach—the polar opposite of the one above—is to remove all requirements and give schools full discretion over spending. The upside to this option is that schools could deploy resources to meet evolving, on-the-ground needs of students. Unlike the more constrained option above, this option would encourage schools to combine DPIA with other funding streams rather than seeing DPIA as discrete “add-on” dollars. The obvious risk is that schools will make poor decisions. To guard against this, lawmakers could demand stronger accountability for student outcomes and task ODE with more rigorous oversight of DPIA spending (while setting aside a small portion of funds to support its new responsibilities).

One legislative option could entail putting more teeth into a current statute that requires the agency to flag districts and schools that produce unsatisfactory results for economically disadvantaged students.[2] Under current law, the only requirement of such “watch” schools is to submit an improvement plan to ODE. There are no consequences. Lawmakers could fix this by demanding a formal state evaluation of DPIA spending in districts and schools that are consistently on the “watch” list. They could also charge ODE with offering, based on its evaluation, recommendations and supports that would require (or strongly encourage) schools to adopt effective practices and programs. Last, in cases of chronic underperformance, the legislature could even require DPIA funds to be withheld.

***

Over the years, Ohio has commendably directed more state aid to schools that serve higher numbers of economically disadvantaged students. Under the new school funding system, it’s poised to steer even more dollars that way. Unfortunately, though, the state has done too little to ensure that schools are putting these dollars to good use. Revisiting the spending requirements and oversight policies for DPIA should be on policymakers’ agendas this year. The approaches outlined above would require bold and steady leadership, but making sure schools leverage funds to benefit low-income students is crucial to ensuring great educational opportunities for all.

[1] Due to recent changes in state law passed last year, schools have eight additional options (largely related to mental health and social-service supports), which were incorporated from the state’s former Student Wellness program. Schools must now also create a plan for using DPIA funds in collaboration with another public or nonprofit agency.

[2] This is in addition to the federally required identifications of low-performing schools (i.e., “comprehensive” and “targeted” school improvement).