Back in July 2019, Ohio lawmakers suspended the school funding formula, the policy mechanism that is supposed to drive state money to school districts and public charter schools. Having just taken office, Governor DeWine was unlikely to wade deep into school funding debates and in fact focused primarily on a proposal to boost funding for student wellness. With respect to the formula itself, Statehouse legislators generally expressed an unease with it but a lack of consensus around a replacement seems to have led them to hit the pause button. Hence, districts’ state funding amounts in FYs 2020–21 have generally been the same as they received in FY 2019.[1]

With the election over, state legislators will soon be turning their attention to the next biennial budget for FYs 2022–23. The Cupp-Patterson plan will surely continue to receive attention as a potential funding formula, but even if it doesn’t pass, legislators should make it a priority to get Ohio back to a formula-driven system. While the “formula” may sound wonky and technocratic, it also serves vital purposes. Let’s review in more detail why a functioning formula is so important.

First, Ohio’s formula works to ensure that funding is based on student enrollment. Ohio’s funding formula (as it existed in FY 2019) is purposefully designed to send state money to districts and charters based on their current pupil enrollments. This feature adheres to the principle of funds following students. In addition to funding based on overall enrollments, Ohio’s formula also ties additional dollars to students in specific categories: students with disabilities, English language learners, economically disadvantaged pupils, career-and-technical education students, and students in grades K–3. These “categorical” funding streams ensure that schools receive extra resources when they serve students who need additional supports.

There’s one caveat to mention, however. While it’s fair to say that the formula deployed in 2019 was generally based on pupil enrollment, it deviated from this model through the use of caps and guarantees. Because of the cap, dozens of districts, many of which are experiencing enrollment gains, did not receive state funding increases commensurate with their growth. Conversely, certain districts with declining enrollment received extra state dollars—above and beyond their formula prescription—effectively funding “phantom students.” In short, both the cap and guarantee function outside of the formula and undermine its ability to drive money based on enrollment and wealth.

Second, the formula helps to level the playing field between districts of varying local wealth. In addition to allocating money based on enrollment, Ohio’s formula also takes into account the ability of districts to generate local revenue, which accounts for just over 40 percent of total K–12 education funding. The Ohio Department of Education puts it this way:

Historically, each district relied exclusively on its property taxes to support education, and most of the proceeds from these taxes went towards funding education. The problem with that arrangement was that since the property tax bases of different school districts varied widely, the educational services they provided also differed vastly. In response, Ohio intervened to provide money to school districts through the foundation formula. This foundation funding narrows the gaps in education funding between wealthy and poor school districts and increases funding equity.

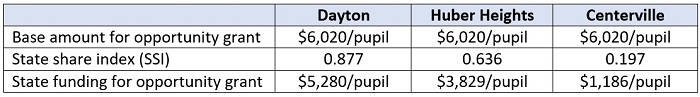

The key feature in Ohio’s current formula that works to meet these equity goals is the state share index (SSI). This mechanism adjusts funding amounts based on districts’ capacity to generate local money (i.e., their property values and resident income). The wealthier the district, the less state money it receives. The table below, using data for illustration from three Montgomery County school districts, shows how the index works in practice. Dayton is a poor, urban district, Huber Heights is a working-class suburb, and Centerville is a wealthy suburb. The calculations displayed below apply to their opportunity grant, the main funding stream within the overall formula. What’s evident from this table is that the SSI ensures that the two less affluent districts receive more dollars than Centerville, the wealthiest of the districts shown below.

Table 1: An illustration of the state share index in action (FY 2019)[2]

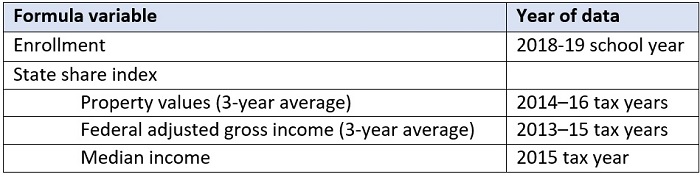

Third, the formula adjusts to changes in enrollment and wealth. District and charter school enrollments change from year-to-year, as do the wealth of districts. Districts, for instance, might get an influx of new students due to the closure of a local non-district school and demographic shifts could also affect yearly headcounts. They could also gain wealth in a short period of time through economic development, thus reducing their need for state aid; conversely, a district might see declines in wealth and need more help. Ohio’s formula takes into account these types of changes, basing funding on current-year enrollments of districts and charter schools. It also uses recent years of data about property values and resident incomes to compute state funding amounts. The table below displays the years of data that were used to calculate funding amounts in FY 2019. The slight lag in the property values and income data reflects a policy that calls for the SSI to be computed just once, in the first year of the two-year budget cycle.

Table 2: Data used to compute districts’ state funding amounts (FY 2019)

With a suspended formula, the state has ignored changes in district enrollment and wealth. Much like the cap and guarantee, the frozen formula has basically created a system of winners and losers, just at a statewide scale. Districts with rising enrollments or declining wealth “lose”—they are shortchanged relative to their present needs—while districts with falling enrollments or increasing wealth “win” because they receive more dollars than they should. In sum, suspending the formula yet again would further aggravate these problems. The state would be funding districts in FYs 2022–23 based on outdated enrollment and wealth data—hardly a fair or sensible method of divvying up state money.

* * *

Though it may never be perfect—and it’s certainly complicated—Ohio’s school funding formula is critical to ensuring a fair allocation of state funds. It works to direct state resources to the districts and charter schools that students actually attend. It also drives more dollars to districts that need state aid the most. Restarting a formula-based system, whether that is the current framework or another one that works to achieve these same ends, is something that Ohio’s next General Assembly must work towards.

[1] District “foundation aid,” which represents the bulk of state funding, was frozen but districts received additional dollars in FYs 2020-21 through the new student success and wellness fund. Total state funding amounts could also increase or decrease depending on the number of students exercising choice options. Charter school funding was not frozen; they’ve been paid based on current-year enrollments.

[2] Data were retrieved via Ohio Department of Education, District Payment Reports (FY 2019). Districts generally reach (or exceed) the full opportunity grant base amount through a state required 2 percent local property tax. The SSI ranges from 0.05 to 0.90, with higher values prescribing a higher state share of the base amount. Public charter schools effectively have an SSI of 1.0—they receive full base amounts—because they receive, with only a few minor exceptions, no local revenue. The SSI also applies to several other formula components, such as categorical funding for students with disabilities and English language learners.