It’s one of those perennial ideas in education reform that never seems to get across the finish line: raising the standards for who can teach in our schools. Advocates on the left and right argue that if we could emulate the highest-achieving nations and recruit from the top of our college classes instead of the middle or the bottom, we’d see higher achievement too. (We could also cut lots of red tape and focus on empowering talented educators to make more key decisions.)

To its credit, Ohio has already revamped its licensure system in an attempt to raise the bar. (For more on how the system works, see here.) Ohio’s teacher residency program is a key part of this structure. Beginning teachers must take part in the four-year residency program. The program offers new teachers mentorship, collaboration with veteran educators, professional development, and feedback. It also includes the Resident Educator Summative Assessment (RESA), which requires teachers to electronically submit a portfolio that demonstrates their teaching abilities based on the Ohio Standards for the Teaching Profession. In order to earn a renewable professional license, beginning teachers must pass RESA and complete four years in the residency program.

As I noted in a previous analysis, the program and its assessment have drawn mixed reviews. Most of the criticism has centered on RESA, which has been accused of being too cumbersome and failing to provide immediate, direct, and specific feedback. Complaints about the assessment were strong enough that the entire program was nearly eliminated during the most recent state budget cycle.

Thankfully, that didn’t come to pass. But in response to concerns, RESA’s designers did revise the assessment. Here’s a look at three of the most impactful changes to RESA, as discussed in its updated guidebook.

1. What resident educators must do

The most obvious change is the number of tasks that resident educators must complete. Last year’s version of the RESA consisted of four separate tasks: 1) first lesson cycle task, which includes the submission of a classroom video 2) communication and professional growth task 3) second lesson cycle task, which includes a second classroom video submission 4) formative and summative assessment task. As you can see from the submission timeline below, the deadlines for these tasks were spread out over the course of the year.

This year’s RESA, on the other hand, requires only one task: the lesson reflection. The updated submission timeline looks like this:

The drop from four tasks to one is an obvious decrease in the amount of work required of resident educators. But to get a better picture of just how significant the change is, it’s worth investigating the dramatic reduction in what teachers are required to submit. According to the 2016-17 RESA guidebook (no longer available online), resident educators were required to submit seventeen different forms, two separate classroom videos for observation purposes, and multiple and varying types of classroom evidence (like examples of communication with parents and caregivers). These submissions were evaluated using upwards of twenty-eight different rubrics, with some submissions being evaluated on the same rubric more than once. Compare those numbers to the new RESA framework, where the Lesson Reflection task includes the submission of only two forms and one classroom video for observation purposes.

2. How resident educators are graded

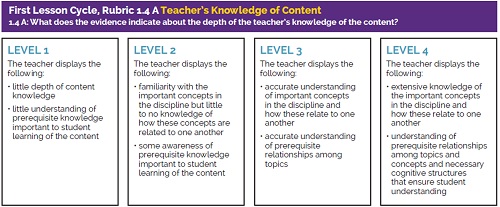

The revised RESA changes not only what teachers must do, but also how they are graded. According to the 2016-17 RESA guidebook, here’s the way a teacher’s content knowledge was evaluated based on a video recorded lesson for the first lesson cycle:

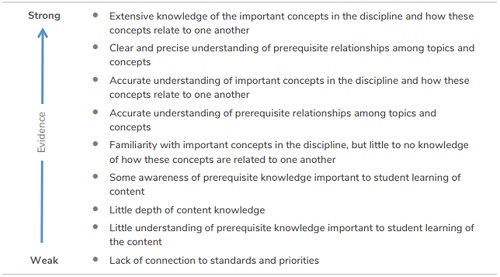

Compare that to the way a teacher’s content knowledge is evaluated on the revised RESA:

There is an obvious difference in structure between the two. But if you look closely, the actual descriptions of a teacher’s abilities haven’t changed—all that’s changed is how these descriptions are arranged. Rather than a rubric that places teachers into specific buckets, teachers will now be placed on an evidence continuum.

The continuum is arguably a better representation of performance, since it more clearly acknowledges that there might only be a very small difference between two teachers previously labeled level two and level three. But how teachers will be graded along this continuum isn’t totally clear.

Unfortunately, there are also still a ton of key details missing that would have been helpful for beginning teachers. For instance, how does a teacher adequately demonstrate a “clear and precise understanding of prerequisite relationships among topics and concepts”? What does that look like for a fourth-grade science class versus a ninth-grade literature class? Sure, it’s a lot more work to give solid examples of each type of evidence, but it could also be profoundly helpful for those taking the assessment. Teachers are taught to give their students exemplars—it seems like a missed opportunity for RESA not to do the same.

3. How resident educators receive their grades

Under previous versions of RESA, resident educators received their score reports on June 1—close to, if not after, the last day of school. Because score reports were delivered so late in the year, many teachers didn’t have the opportunity to discuss their results and next steps with their mentors. The original score reports also contained a limited amount of feedback. Many teachers argued that the limited feedback was unhelpful, particularly in light of the fact that RESA was designed to help beginning teachers analyze and reflect on their own practice.

The new score reports will be delivered to resident educators by May 15, which should provide more time for teachers to discuss their scores with their mentors. These reports will purportedly provide more comprehensive, concrete feedback that teachers can then use to improve their practice. Until this year’s crop of resident educators gets their actual score reports back, it’s impossible to know whether the feedback really is more helpful. Nevertheless, it’s a step forward that the problems with feedback have been recognized and attempts are being undertaken to course correct.

***

Only time will tell if the revised RESA is a better tool for novice teachers and those who are charged with their development. The Ohio Department of Education and RESA’s designers deserve credit for listening to feedback of those who are impacted by its administration and results and making modifications to the assessment. But as with any policy shift, it’s important that policymakers and stakeholders keep a close eye on the changes going forward.

RESA should absolutely give quality feedback to beginning teachers and be streamlined enough that it is not burdensome. But as part of the teacher licensure system, it must also continue to hold a high performance bar for those who educate Ohio’s students. After all, it’s their educational success that hinges on how effective their teachers are.