“Government by the people” is one of the most powerful ideas in American government. It represents the belief that, in a democracy, the people hold sovereignty over government and not the reverse.

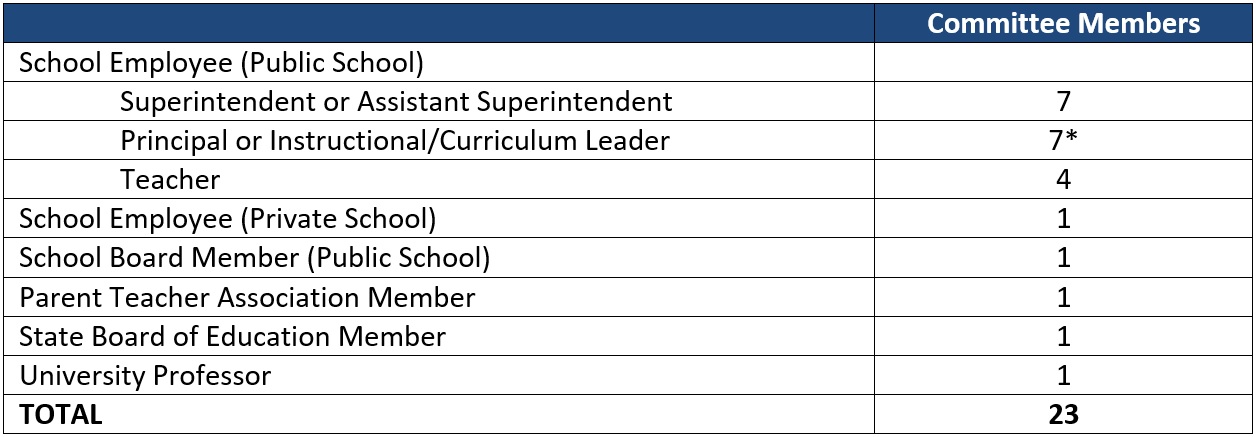

I bring this up as a way of considering how far we can deviate from this ideal. Take a look at Ohio’s newly formed assessment committee, which is charged with the important task of reviewing assessment policies. While this is an “advisory” committee with no formal policymaking authority, one expects its recommendations to make headlines and capture legislator attention. The state superintendent recently appointed twenty-three committee members and it’s almost entirely comprised of government (i.e., public school) employees. As you can tell from the table below, public school administrators, principals, and teachers hold eighteen of the twenty-three seats—a large majority.

* One member is considered tentative

Administrators and teachers should definitely be part of this conversation. But it’s not right to stack this committee with public employees whose own interests are also at stake. For instance, it’s no secret that many school officials want to weaken Ohio’s assessment and accountability policies. One reason: Their lives get easier when the state waters down assessments (and accountability based on them). Under an “A’s for all” approach, they’ll surely face fewer nosy questions from their boards, parents, and community members about how well their schools are preparing kids for college and career. It may even increase the likelihood that levies pass and lead to pay raises for them and their staff.

It’s a shame that this committee couldn’t have been more representative of families, taxpayers, and employers. They too have a stake in how Ohio assesses and reports student learning. Parents have an interest in their own kids’ state test scores, as well as how their school handles matters of state (including test prep) and local assessments. Taxpayers, more broadly, also have an interest in assessment and accountability policies. Given the amount we spend on K-12 education—roughly $20 billion per year in local, state, and federal dollars—they deserve honest gauges of how students and schools are doing based on objective achievement data. Finally, Ohio’s employers should be an engaged partner in this conversation as well. They rely on a strong K-12 school system to meet their workforce needs in a competitive, global marketplace. Understanding this, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce has been one of the staunchest advocates of higher standards and strong accountability policies.

Assessment and their related accountability policies affect Ohioans everywhere. Yet the recently formed review committee doesn’t reflect a wide spectrum of voices. It’s almost entirely comprised of public employees with their own narrow interests. Whatever the committee recommends this summer should be taken with a hefty grain of salt.