Due to massive financial woes, Ohio suspended cost-of-living adjustments (COLAs) for retired teachers in July 2017. At that time, the State Teacher Retirement System, or STRS, had racked up a staggering $24 billion in pension debt—i.e., “unfunded liabilities,” the difference between promised retirement benefits and the assets available to pay them.

Suspending COLAs—and a booming stock market—has slightly improved STRS’s finances. But the system remains $21 billion in the hole as of July 2021, and the absence of COLAs, combined with significant spikes in inflation, has left many retirees understandably upset. In response, last month STRS approved a one-time 3 percent COLA. That adjustment should bring some relief, but it’s only half of what social security gave retirees last year (Ohio teachers don’t participate in social security). It must be emphasized that this is a one-time adjustment—not an ongoing promise. System leaders likely balked at the fiscal implications of anything more permanent, as actuaries estimate that an ongoing 2 percent COLA would add another $14 billion to the system’s liabilities. Yikes.

The latest skirmish over COLAs is just one symptom of an ailing system. Not only are teacher pensions in Ohio underwater and disadvantaging retirees, but they also exact a financial toll on school districts and current teachers.

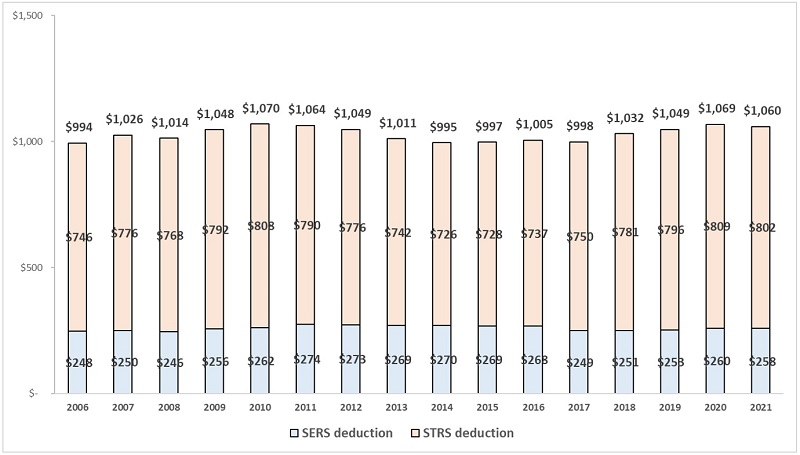

Let’s start by looking at the cost to employers. Ohio requires school districts to pay 14 percent of their payroll to state-run retirement systems, whether the one for teachers (STRS) or for other school employees (SERS). This “payroll tax”—as one might call it—cost districts $1.6 billion in FY21. That amounts to just over $1,050 per pupil or about 8 percent of their overall operating expenses. Interestingly, districts’ pension costs have remained largely flat over the past fifteen years, likely reflecting a constant employer contribution during this period. The per-pupil amount Ohio districts spend today on pensions tracks fairly closely with the national average.

Figure 1. Employer share of pension costs per pupil, Ohio school districts, 2006–21 (inflation adjusted)

Source: Author’s calculations based on Ohio Department of Education, Statements of Settlement for traditional school districts and their enrollment data. Dollars are inflation adjusted to 2021 prices using the consumer price index. This figure only reflects the employer’s share to pension costs (it does not include the worker’s share).

Analysts have long raised concerns about committing such sizeable sums for pension payments, as it crowds out other uses of school funds. To illustrate, consider what would happen if Ohio reduced the required district contribution to 12 percent, a rate closer to the average private employer’s contribution (social security tax plus retirement benefits). This would free approximately $170 million per year for districts, an amount that would allow for a salary increase of $1,700 for every Ohio teacher.[1] Given STRS’s fiscal problems, reducing the employer contribution is unlikely. Yet the example illustrates how pensions saddle schools with inflexible costs that restrict their ability to pay higher salaries or meet other critical needs.

But the employer side is only half the story—and half the cost. The “true” per-pupil expense of the pension system is nearly double what is shown in Figure 1, because Ohio teachers are required to contribute 14 percent of their salary to STRS and nonteaching staff pay 10 percent to SERS. Thus, school districts and their employees together pay approximately $2,000 per pupil for pensions.

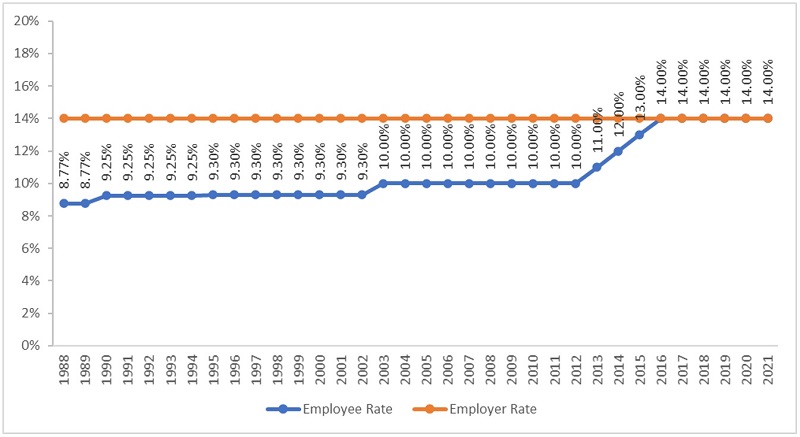

Unlike the employer rate, teachers’ required contributions have steadily increased over time. Figure 2 shows that back in 1988, Ohio teachers paid a relatively modest 8.77 percent of their salary into the pension system. That rate has climbed since then and now stands at 14 percent.

Much like higher taxes, increasing the employee contribution rate reduces the take-home pay of teachers. For an Ohio teacher earning the state average salary of $65,000 per year, a 14 percent contribution subtracts $9,100 from her annual salary. On top of that are federal and state income taxes, property taxes, and…well you get the story. There’s not all that much left. Of course, it’s not uncommon for workers to be required or incentivized to fund retirement. But even if the contribution rate for Ohio teachers was 10 percent—STRS’s employee rate from 2003–12 and SERS’s current rate—it would put $2,600 more per year in the average teacher’s pocket.

Figure 2. STRS employer and employee contribution rates, 1988–2021

Source: STRS Annual Comprehensive Financial Reports.

Ohio’s teacher pension system is a massive expense for schools and teachers—and it doesn’t even reliably deliver benefits to help retirees deal with inflation. We don’t have the space here to discuss the ways that pension systems cheat young teachers or those who leave the profession earlier than the retirement age (topics for another day). And as pensions expert Chad Aldeman found, Ohio teachers—even those who stay to retirement age—would actually be better off choosing the state’s rarely used 401(k)-style plan. Given the high costs and mediocre benefits, one might ask the following: Is it time for something better? Ohio does have policy options besides continuing this legacy system, and I’ll discuss those in a future piece.

[1] In FY 21, Ohio districts paid $1.20 billion into STRS, implying their teacher payrolls were $8.57 billion (0.14 * $8.57 billion = $1.20 billion). Reducing the employer contribution to 0.12 would have cost districts $1.03 billion in teacher retirement payments. The difference ($1.20–$1.03 billion) is divided by the roughly 100,000 teachers in Ohio yielding a potential raise of $1,700 per teacher.