By now, it’s no secret that the pandemic and schools’ pivot to remote learning was a disaster for most students. Various studies have documented severe learning losses based on both national and state assessment data. The federal government sent an unprecedented $200 billion to U.S. schools to help students get back on track, and schools are supposed to be spending these dollars on remediation efforts. Yet students are still far from caught up, and a recent analysis led by a team of Harvard and Stanford researchers is another clarion call for strong academic recovery.

Known as the Education Recovery Scorecard, this ambitious project relies on pre- and post-pandemic data from 2018–19 and 2021–22 to gauge changes in math and reading performance in districts across the nation. The Scorecard adds important new perspective on the academic declines, both nationally and right here in Ohio.

First, the analysts estimate how many grade levels behind current students are compared to their pre-pandemic peers. This way of reporting learning loss may be more intuitive for the general public, and offers a clearer sense of the work needed to help students recover lost ground. Tom Kane, one of the lead researchers, notes, “The hardest hit communities…where students fell behind by more than 1.5 years in math would have to teach 150 percent of a typical year’s worth of material for three years in a row—just to catch up.”

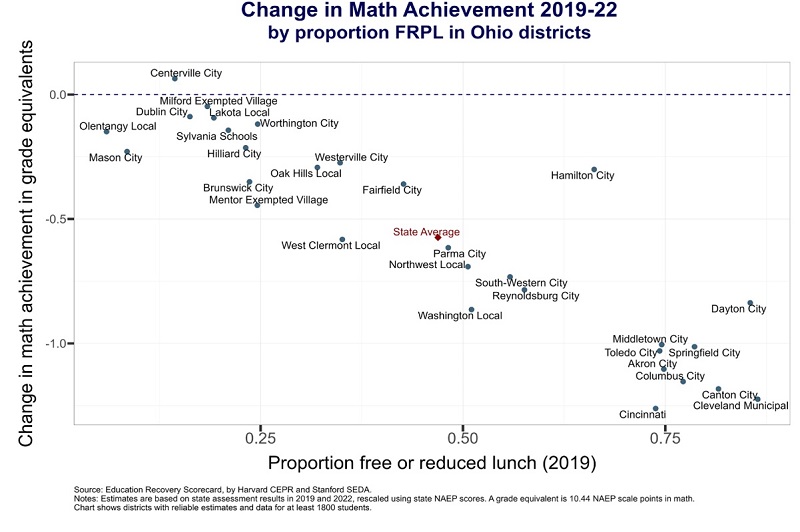

Put this way, the academic catastrophe in Ohio’s high-poverty, urban districts comes into even clearer light. Consider the charts below, the first of which displays the learning losses of selected Ohio districts in math. We, first of all, see a correlation between districts’ learning losses and student poverty rates. At the top left corner are several affluent districts that came away relatively unscathed by the pandemic. Towards the middle of the chart, we find the statewide average loss of just over a half grade level in math, along with some mid-poverty districts.

But at the bottom right corner are districts such as Cincinnati, Cleveland, and Columbus, where students are more than a grade level behind their pre-pandemic counterparts. Using Kane’s rule of thumb, Columbus students, for example, need about a year and half of instruction—for two years—to catch up to their pre-pandemic peers attending the district. Keep in mind that Columbus students were already lagging well behind state and national averages prior to the pandemic. In 2019, the typical Columbus student was 2.5 grade levels behind the national average. In 2022, she was a staggering 3.6 grade levels behind.

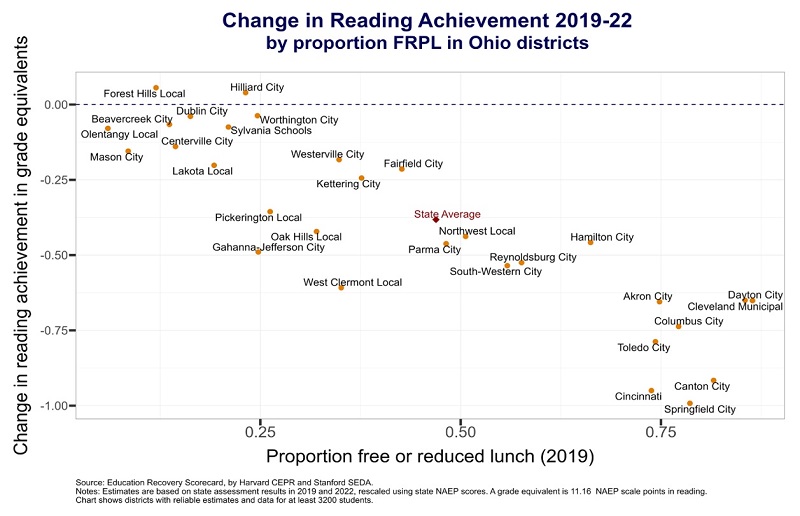

Results follow a similar pattern in reading, though the declines in this subject are not quite as steep as in math. The average student in Ohio is about two-fifths of a grade level behind their pre-pandemic peers; in high-poverty urban districts, they are between a three-fifths and a full grade level behind.

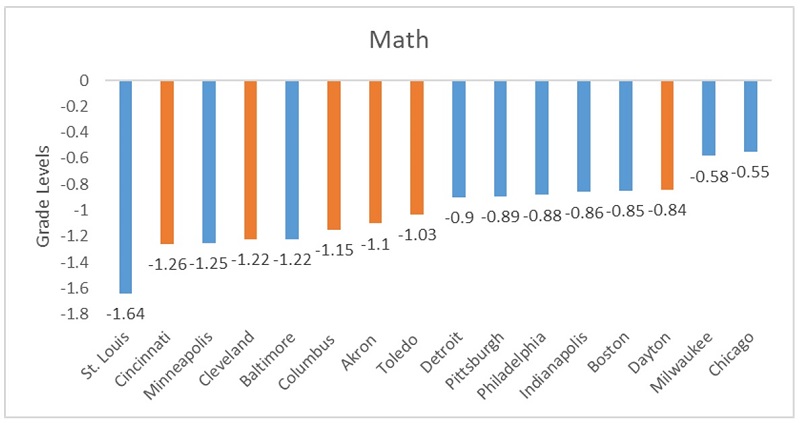

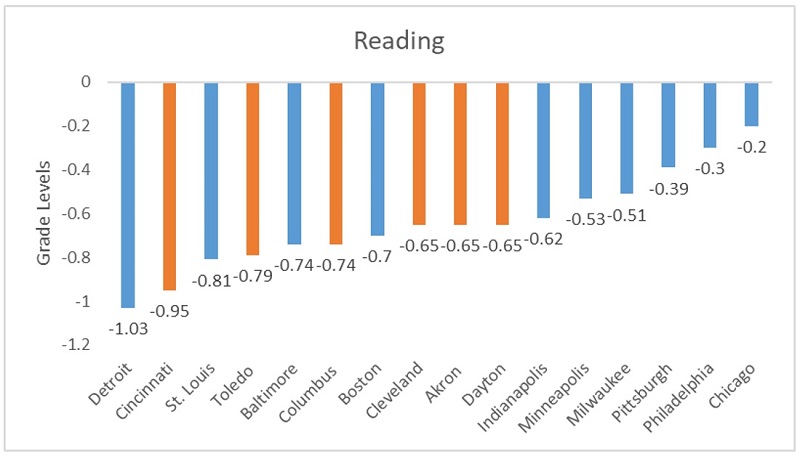

The Scorecard also allows for cross-state comparisons of learning loss. One can gauge how students in Cleveland or Columbus fared during the pandemic compared to their counterparts in Detroit, Indianapolis, or Pittsburgh. This unparalleled picture of learning loss across state lines is made possible through statistical methods that crosswalk districts’ state exam scores with state-level results from the 2019 and 2022 rounds of the National Assessment of Educational Progress.

Sobering results emerge when comparing Ohio’s big-city results to other urban districts in the Northeast and Midwest. The top figure shows that the learning losses in Cincinnati, Cleveland, Columbus, Akron, and Toledo exceeded those of many other cities—and were roughly double the losses in Milwaukee and Chicago. Of the large urban districts in Ohio, Dayton suffered the smallest declines in math.

The results are broadly similar in reading, with Ohio’s large urbans faring somewhat poorly compared to other districts in the nation. Why some urban districts weathered the storm better than others is a tough question to answer definitively. It’s likely related to how long schools were closed, what types of supplemental opportunities they’ve offered students, how the pandemic affected their teaching workforce, and other variables. A recent study by analysts engaged in the Scorecard sought to identify the most significant factors, but found that “no individual predictor [of learning loss] provided strong explanatory power.”

* * *

Kane and Sean Reardon, the other lead researcher for the Scorecard project, offer a number of solid ideas in a New York Times editorial about how to help students catch up. Among them include summer programs, awareness efforts, and tutoring. Consistent with those suggestions, I wish to highlight three specific steps that Ohio schools—especially those in urban areas—can immediately take to support students who have fallen behind.

1. Make good use of this summer. Schools should strongly encourage, or even require, students who score at the lowest level (“limited”) on this spring’s state assessment to participate in summer learning programs. Extra learning time above and beyond the typical school year is absolutely critical to helping students get caught up.

2. Send state exam results to parents ASAP. Recent survey data from Learning Heroes indicates that nine in ten parents believe their child is on grade level, likely reflecting the rosy grades that come home via report cards (four in five parents say that their children receive mostly A’s and B’s). This misinformation can do real harm to students, as they miss out on the extra supports their parents would otherwise secure if they knew the truth. State exams often provide a more realistic picture of academic proficiency, and schools need to make sure that parents receive these results right away so they can act swiftly on behalf of their children.

3. Inform parents about the ACE account program. In 2021, Ohio created a new program known as the Afterschool Child Enrichment (ACE) account. It currently provides low- and middle-income parents $1,000 per child that they can use to cover the costs of learning opportunities, such as afterschool tutoring, day camps, and music and art lessons. Schools should be informing parents of this program and proactively encouraging them to apply for the funds. Much like summer school, students stand to benefit when they have extra time and learning supports.

The pandemic has thankfully receded and isn’t at the top of our collective consciousness anymore. But its effects are still being felt, most of all by our youngest citizens. To do right by students who have fallen off track, state and local leaders need to do everything in their power to support a strong recovery.