At the end of June, Ohio lawmakers passed House Bill 110, the biennial operating budget for FYs 2022–23. It included a new school funding framework that received bipartisan support and was backed by school district officials and teachers unions. But formulas don’t always have a long shelf life; this will be Ohio’s fourth within the past fifteen years. So will this framework stick, or will it suffer the same fate as prior ones? There are reasons to believe that future lawmakers will stay with this model, but some causes for doubt, too.

The new approach

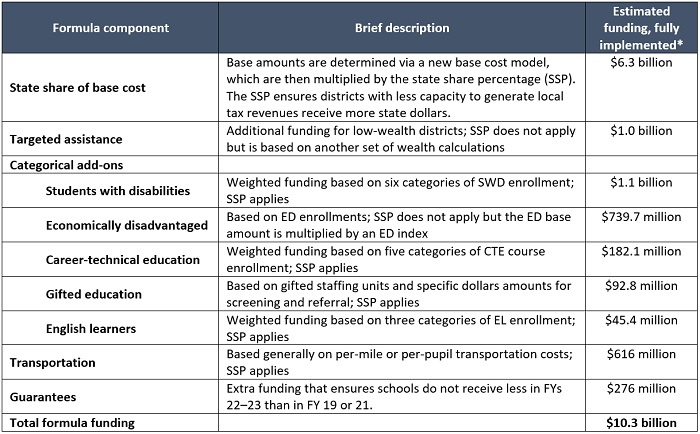

Before turning to predictions, we should first familiarize ourselves with the framework—and see how it differs from prior efforts. Table 1 begins by offering a high-level look at the components of the new formula. The estimated funding levels are included to illustrate the relative size of the components, but due to the phase-in of the new model, these are not the actual amounts that will flow in FYs 2022–23. The table displays the elements that apply to school districts. Charter and STEM schools are eligible to receive all the components with the exception of targeted assistance, gifted, and transportation (though they may receive reimbursement from the state if they provide it).

Table 1: An overview of the HB 110 funding formula

* These are LSC estimates based on an earlier iteration of the funding plan that is largely similar to the one passed in HB 110 (more recent estimates aren’t available). These amounts assume a fully implemented formula, something that will not occur in FYs 2022–23. Due to the increased costs of the new model, legislators chose to phase-in the spending increases (33 percent of the increase by FY 2023).

The overall structure should look familiar to Ohio’s policy wonks. Akin to the previous formula, there is a “core” base funding component, targeted assistance, and various categorical add-ons. But there are significant differences, as well. (Another key change, not discussed below, is to “direct fund” choice programs, a topic previously covered.)

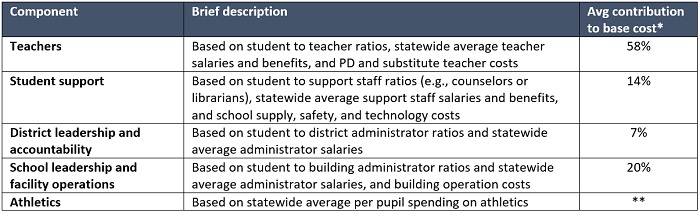

- Base cost calculations. The core of the new formula is the state share of base cost (SSBC), which replaces the opportunity grant (OG). While the OG simply set a fixed base amount that applied to all districts—most recently $6,020 per pupil—the new model includes detailed “base cost” computations that yield variable base amounts for each district. Those calculations also produce a much higher base, averaging $7,200 per pupil under a fully implemented formula. Table 2 displays an overview of the base cost model for districts. Most of the calculations rely on set staffing ratios that determine the number of employees assumed to be needed in a district. That number is then multiplied by the statewide average salary for a staffing position from FY 2018 to yield an assumed cost of an “input.” A few other calculations—such as technology costs or co-curriculars—rely on a statewide average per-pupil expenditure or a flat amount set in law. Charters and STEMs follow a similar model, but their costs are computed based on statewide district average costs for the support staff, district administration, and school administration and operations components.

Table 2: An overview of the HB 110 base cost model

* These are LSC estimates based on an earlier iteration of the funding plan that is largely similar to the one passed in HB 110. ** In the earlier version of the funding plan, the athletics cost component was part of the student support base-cost component, but in the final legislation, it became a standalone component.- New equalizing mechanism. To ensure that lower wealth districts receive more state aid, the SSBC and several other components apply a new “equalizing” mechanism to funding amounts. This lever, known as the state share percentage (SSP), replaces the formerly used state share index (SSI). One of the key differences is that the SSP now incorporates resident income consistently in all districts’ calculations, whereas the SSI only included income under certain conditions. In the new formula, the SSP will be calculated based 40 percent on a district’s resident income and 60 percent on its property values.[1]

- Tweaks in categorical funding. HB 110 maintains longstanding policy by allocating extra dollars to schools serving students with certain characteristics. Yet it makes a few noteworthy revisions. One is a shift away from using straight-up dollar amounts—e.g., adding an extra $1,515 per EL pupil—to multipliers that now fund an EL student at 1.21 times the statewide average base amount. This weighting system ensures that proportional relationships across categories are properly maintained even when the base changes. The new system also alters some of the categorical funding streams. Those include an increase in the economically disadvantaged base from $272 to $422 per pupil, a boost to gifted funding (e.g., raising identification funding from $5 to $24 per pupil), and changes in the definitions of an EL student.

Will this formula stick?

A pessimist’s view first: The most glaring problem is cost. Fully implemented, the new model calls for roughly $2 billion in additional state outlays, an increase of approximately 20 percent over current state expenditures on K–12 education. That amount is driven largely by the sizeable increase to the base amount. Faced with that sticker price, lawmakers chose to pay down just a portion of it over the next two years. Will the next General Assembly be as enthusiastic about this plan and continue its phase-in? Just as daunting is the prospect of millions (billions?) more in additional spending if and when the base cost model is updated with more current salary and expenditure data. Remember, HB 110’s base cost formula relies on FY 2018 staff salaries and benefits. What happens down the road if 2023 or 2025 data are used—especially with the massive federal relief packages making their way to schools? Will future lawmakers go back to the drawing board?

Despite the challenges that lie ahead, there are also good reasons to think the formula will stick. The first is political. The school establishment, which exerts significant influence in the Statehouse, championed this funding model. They aren’t going away and are likely to work to protect the formula and continue pushing for full implementation. Moreover, unlike previous formulas that were closely tied to a sitting governor, this model was developed by legislative leaders—particularly those in the House—which may allow it to better stand the test of time.

A second reason for optimism is that HB 110 makes commendable changes that streamline the system and address structural problems of prior formulas. It now directly funds school choice programs from the state instead of routing those dollars through districts. The new model also makes simplifying changes such as the across-the-board incorporation of districts’ incomes into the SSP, the elimination of funding “caps,” and the removal of a few smallish add-on components.

Color me an optimist, but my view is that the general outline of the HB 110 formula will take hold. And that wouldn’t be such a bad thing. Constantly overhauling formulas creates less fiscal certainty for schools, weakens public confidence in the system, and results in inefficient hold-harmless policies such as “temporary transitional guarantees” that are anything but temporary. That being said, future lawmakers are apt to struggle to fully pay for the model, leading them to either tweak its structure in efforts to control costs or continue underfunding it. In the end, no formula is perfect and funding policy will always be subject to great debate. Nevertheless, this framework might just be the one that lawmakers can work—and live—with for the years ahead.

[1] The SSP can range from 5 to 100 percent. Assuming a base of $7,000 per pupil, a low-wealth district with an SSP of 80 percent would receive $5,600 though the SSBC; a high-wealth district with an SSP of 20 percent would receive $1,400 per pupil. The remainder of the base amount is assumed to be covered by a state-required 2 percent property tax. The SSP does not apply to charter and STEM schools’ funding amounts because they have no local taxing authority.