Stephen Dyer, longtime critic of public charter schools, now employed by the anti-charter-schools teachers union, recently wrote a lengthy response—a so-called “evaluation”—to the charter school study by Ohio State’s Stéphane Lavertu and published by Fordham. He accuses us of “cherry picking schools; manipulating data; [and] grasping at straws,” and he lodges a number of other complaints, some of which have little to do with the study itself.

The following responds to his criticisms. Excerpts from Dyer’s piece are reprinted below and italicized; my responses follow them in normal font.

* * *

“The group’s latest report—The Impact of Ohio Charter Schools on Student Outcomes, 2016-2019—is yet another attempt to make Ohio’s famously poor performing charter school sector seem not quite as bad (though I give them kudos for admitting the obvious—that for-profit operators don’t do a good job educating kids and we need continued tougher oversight of the sector).”

The purpose of this study isn’t to make Ohio charter schools look “good” or “bad”—it’s to offer a comprehensive evaluation of charter school performance that can drive an evidence-based discussion about charter school policy. To that end, we asked Dr. Stéphane Lavertu, a respected scholar at The Ohio State University, to conduct an independent analysis of charter performance. His research relies on the most recent data available (2015–16 through 2018–19) and uses rigorous statistical methods that control for students’ baseline achievement and observable demographic characteristics to isolate the effects of charters apart from the backgrounds of the pupils they enroll. Had Lavertu’s analyses revealed inferior performance, we would have published that, too. (Fordham has released studies that found mixed results for choice programs in the past.) The data, however, reveal superior performance among Ohio’s brick-and-mortar charter schools (see page 13 of the report), with especially strong, positive impacts for Black students (page 14). When all charters are included in the analysis (including e-schools and dropout recovery), charter students still make significant gains in English language arts (and hold their own in math) relative to similar district students in the most recent year of available data (page 24).

Apparently, these results don’t fit with Dyer’s agenda, so he would rather question the motivations of the study. He is also wrong in claiming that “for-profit operators don’t do a good job educating kids.” On the contrary, the study finds that, in grades four through eight, brick-and-mortar charter schools with for-profit operators outperform districts that educate similar students (see page 17). Yes, you read that right. The results of charters with non-profit management operators, however, do outpace those opting to contract with for-profits.

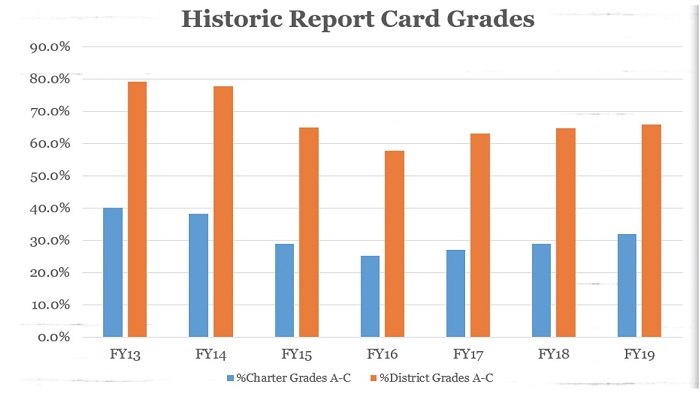

“But folks, really. On the whole, Ohio charter schools are not very good. For example, of all the potential A–F grades charters could have received since that system was adopted in the 2012–2013 school year, Ohio charter schools have received more F’s than all other grades combined.” [Following figure is his.]

This is a ridiculous apples-to-oranges comparison. In fact, given Dyer’s lede (and keeping with the produce metaphors), it seems only fitting to call it an egregious attempt to cherry-pick using data that include much wealthier districts. The figure compares charter school performance to all Ohio school districts statewide, many of which serve students from more affluent backgrounds. Due to longstanding state policy, Ohio’s brick-and-mortar charter schools are concentrated in high-poverty urban areas. In turn, charters serve disproportionately numbers of low-income and minority students who, as research has consistently documented, achieve on average at lower levels than their peers (thus explaining charters’ lower ratings relative to all districts in Ohio).[1] In 2018–19, Ohio charters (brick-and-mortar and online together) enrolled 57 percent Black or Hispanic students versus a statewide average of 23 percent. Charters also enrolled more economically disadvantaged students: 81 percent versus 50 percent statewide.

A fair apples-to-apples evaluation, sans cherry-picking, takes into account these differences in pupil background by comparing the academic trajectories of very similar charter and district students. This is exactly what Lavertu does. What Dyer shows is mostly the achievement gap between students of lower socioeconomic status versus those from more advantaged backgrounds. It’s not evidence about the effectiveness of Ohio charters. Almost everyone realizes that the lower proficiency rates of Cleveland school district students to Solon or Rocky River reflects to a certain extent differences in pupil backgrounds. Why wouldn’t the same apply to Cleveland charter schools?

“Fordham ignored all but a fraction of the Ohio charter schools in operation during the FY16-FY19 school years, including Ohio’s scandalously poor performing e-schools (yes, ECOT was still running then), the state’s nationally embarrassing dropout recovery charter schools (which have difficulty graduating even 10 percent of their students in 8 years), and the state’s special education schools—some of whom have been cited for habitually billing taxpayers for students they never had.”

The report didn’t ignore anything. The focus was intentionally on general-education, brick-and-mortar charters—a point we make clear in the foreword. These schools serve as parents’ primary public-school alternative to traditional district options in the places where charters are allowed to locate. If you’re a parent considering a site-based charter school for your child that isn’t focused on academic remediation, you might want to know how these schools perform on average. (Prior charter evaluations have combined the results of brick-and-mortar charters with those of e-schools and dropout-recovery schools, thus masking brick-and-mortar performance.) So yes, for good reason, there was a focus on brick-and-mortar charters.

Dyer misleads when he says that brick-and-mortar charters represent “a fraction of Ohio charter schools.” In FYs 2016–19, these schools enrolled between 56 to 62 percent of all Ohio charter students (page 23 of the report). That’s a fraction all right. It also happens to be a majority. Importantly, these site-based schools serve 83 percent of all Ohio charters’ Black students and 72 percent of the sector’s economically disadvantaged pupils.[2]

He is also wrong in claiming that the results of virtual, dropout-recovery, and special-education schools were “ignored.” Despite serious methodological challenges in evaluating these schools’ impacts—Lavertu discusses those on pages 11 and 24—the analysis gauges the performance of all Ohio charter schools (page 22–24), and these specialized schools’ results appear separately on page 68.

Moreover, suggesting that Fordham has ignored e-schools over the years is absurd. In fact, we released an entire report in 2016 that focused exclusively on Ohio’s e-school performance, and we’ve been engaged in the policy discussions aimed at improving the quality of online learning—an educational model that, due to the pandemic, almost all of us can now agree has unique challenges.

As for the “embarrassing” graduation rates of dropout-recovery schools, they are likely as much a reflection of the failures of students’ former school—often in their home district—as the charter school in which they subsequently enroll. (By definition, dropout-recovery schools enroll primarily students who have dropped out or are at risk of doing so.) Fordham has called for a more comprehensive way of evaluating dropout recovery charter schools, including a “shared accountability” framework that would split responsibility for students’ graduation (or not) based on the proportion of time spent in each high school.

“The “performance gains” they point to are not impressive.

For example, “Students attending charter schools from grades 4 to 8 improved from the 30th percentile on state math and English language arts exams to about the 40th percentile. High school students showed little or no gains on end-of-course exams.”

Really? A not-even-10-percentile improvement? And none in high school? That’s it?”

Dyer is unimpressed with a 10 percentile gain for charter students attending brick-and-mortar charters in grades four through eight (as opposed to attending district schools). There is some room for debate around what constitutes a “large” or “impressive” effect size, which Lavertu discusses in the report (pages 32–33). Within the context of studies about other educational interventions, Lavertu suggests these effects—which are equivalent to roughly an extra year of learning accumulated over these grades—should be viewed as “large.” Rather than enjoying what researchers would consider large academic gains, it seems that Dyer would prefer that these charter students languish in district schools, staying at the 30th percentile.

As for the high school achievement results, it’s important to note that Dyer quotes from the Columbus Dispatch’s coverage of our report. It’s not a quote from the study. While the evidence is not quite as convincing that brick-and-mortar charter high schools produce large academic gains, the estimates are positive across all four state English and math end-of-course exams—and positive and statistically significant on both English EOCs. Lavertu’s analysis suggests positive effects on ACT scores, though the estimates do not reach conventional levels of statistical significance.

“How about this: ‘Attending a charter school in high school had no impact on the likelihood a student would receive a diploma.’

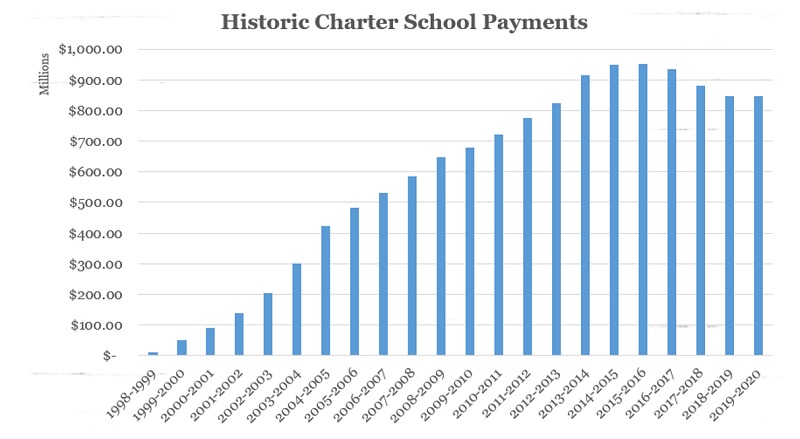

So we spend $828 million a year sending state money to charters that could go to kids in local public schools to have literally zero impact on attaining a diploma?

Egad.” [Following figure is his.]

This chart is nonsense. The reason that charter schools have received increasing amounts of state funding since FY99 is because they’re serving an increasing number of students (see the enrollment trend here). State dollars were simply moving to charters—the schools that were responsible for these students’ educations—as more parents were choosing this educational option. Meanwhile, contrary to Dyer’s suggestion that funding charter schools is an inefficient use of taxpayer money, charters represent a cost-effective educational option as they presently produce statistically equivalent outcomes (in terms of graduation) and superior performance on state exams—all at a lower cost than districts.

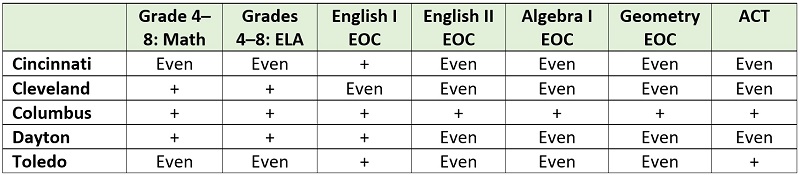

“The report found better performance from charter students in at least one of the math or English standardized tests in five of Ohio’s eight major urban districts (Akron, Canton, Cincinnati, Cleveland, Dayton, Toledo, and Youngstown). Only in Columbus did they outperform the district in both reading and math.

The report ignores that ECOT took more kids from Columbus in these years than any other charter school in Columbus. And, of course, those kids did far worse than Columbus students.

But even cherry-picking students. And data. And methodology, Fordham only found slightly better performance in one of two tests the study examined (again, Ohio requires tests in many subjects, but I digress) in five urban districts, better performance in both tests in one, and no better performance in Cincinnati and Toledo, which lost about $500 million in state revenue to charters during these four years the study examined.”

It’s hard to be sure what’s being referred to here. It does contain a gratuitous ECOT mention designed to incite outrage. It’s true, we didn’t like ECOT either. Dyer seems to express concerns that charters aren’t doing well enough to justify state funding by pointing to specific city-level results. The table below summarizes city-level test results for brick-and-mortar charters in grades four through eight and high school (see pages 16 and 27), and it sure seems that charters are a pretty good investment. On a battery of academic outcomes, charters perform either on par with the local district (i.e., there is no statistically significant difference in results, denoted as “Even”) or produce significant gains (“+”). And keep in mind that charter schools in these cities receive about 70 cents on the dollar in public funding compared to district schools. Seen that way, the return on investment is through the roof.

“Of course, the study also ignored that about ½ of all charter school students do NOT come from the major urban districts, including large percentages of students in many of the brick and mortar schools Fordham examined for this study. For example, about 30 percent of Breakthrough Schools students in Cleveland don’t come from Cleveland. Yet Breakthrough’s performance is always only compared with Cleveland.”

This concern is irrelevant because Lavertu compares very similar charter and district students. Even if the home district of a student attending a Breakthrough school is, say, Parma, she would be compared to a district student with similar baseline achievement and observable demographics. Moreover, he also examines a subset of students who attended the same elementary and middle school—children likely to be residing in the same neighborhood—and then subsequently transitioned to charter or district schools. The results from these analyses are very similar, revealing yet again a charter school advantage. Overall, Lavertu examines charter performance from virtually every possible angle, and the results hold up.

“More than 34 percent of Ohio public school graduates have a college degree within six years. Just 12.7 percent of charter school graduates do.

More than 58 percent of Ohio public school graduates are enrolled in college within two years; only 37.2 percent of Ohio charter school graduates are.”

This is another example of cherry-picking. Again, charter schools educate students of very different backgrounds to the average Ohio district. Though an analysis of post-secondary outcomes was not part of Lavertu’s analysis, state data show that charters’ college enrollment and completion rates, as cited above by Dyer, track more closely with the averages of Ohio’s urban schools—a more appropriate point of comparison. Fifteen percent of urban high school graduates complete college within six years, and 42 percent enroll in college within two years.

“In more than one in five Ohio charter schools, more than 15 percent of their teachers teach outside their accredited subjects

The median percentage of inexperienced teachers in Ohio charter schools is 34.1 percent. The median in an Ohio public school building is 6 percent.”

These teacher statistics have little to do with student outcomes. There is evidence, for instance, based on Teach For America evaluations that less-experienced teachers can perform on par—if not better—than more-experienced teachers.

“During the time period this report examined, nearly $4 billion in state money was transferred from kids in local public school districts to Ohio’s privately run charter schools.”

Fascinating. Money was “transferred from kids in local public school districts” to “privately run charter schools.” In one sector, dollars belong to the kids. In the other, they belong to institutions. Which is it? Of course, the answer is that the dollars belong to kids, whether they attend a district or charter school. When students transfer from, say, Akron to Hudson school district (or vice versa), the dollars should move with the child—a “backpack funding” principle. The same applies for charter schools, and indeed when Ohio students exit a district, the state funding designated for their education moves to their school of attendance (though local funding stays with the district). There is nothing wrong with dollars transferring from traditional districts to public charter schools when students choose an alternative option.

“Maybe the answer, especially during this pandemic, is expanding ‘high-quality’ local public school buildings, or investing at least some of the $828 million currently being sent to Ohio’s mostly poor performing charter schools back to local public schools so they have a better shot at being dubbed ‘high quality,’ thereby expanding the number of ‘high-quality’ options for students?”

We agree that there are exceptionally high performing traditional district schools, and celebrate that fact. At the end of the day, Fordham believes that all high quality schools—whether district, public charter, STEM, joint-vocational, or private—should receive the resources and opportunities to expand and serve more students. In our view, this study clearly indicates that, based on performance, supporting quality charter schools is a promising policy avenue that can unlock greater educational opportunities for more Ohio students.