Interdistrict open enrollment, one of the longest running and most popular forms of school choice, unlocks public school options for more than 80,000 Ohio students. It allows children to attend school in a district other than the one they live in. Under current state policy, district participation in open enrollment is voluntary. Most districts choose to participate, but this year 107 of Ohio’s 608 school districts decided to keep their schools closed to nonresidents, a similar number to previous years.

Here at Fordham, we’ve consistently urged Ohio lawmakers to require all traditional school districts to admit non-resident students. This would increase public school opportunities for students who reside in Ohio’s urban centers, as most non-participating districts surround big cities such as Cleveland, Cincinnati, and Columbus. It would also be more consistent with the state’s approach to public charter schools, which generally must be open to all comers.

Yet one potential difficulty, which we’ve acknowledged in our recommendations, is that districts might be at capacity, with no room in existing schools or classrooms for more children. In those cases, onboarding additional students would pose significant challenges. But are capacity constraints keeping districts from participating? Though no central database reports schools’ building capacities, we can look at enrollment trends to get a general sense of it. This isn’t a perfect method: districts with declining enrollment might have gone from 110 percent capacity to 105 percent, for example, and we would not know it. Still, it’s fair to assume that, in most places, declining enrollment implies that extra seats are available.

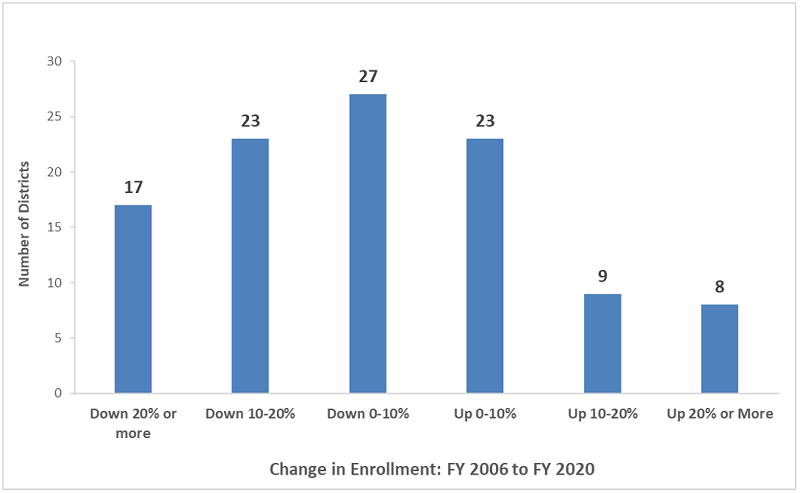

Lo and behold, as figure 1 shows, a large majority of non-participating districts have lost students. From 2006 to 2020, sixty-seven of these 107 districts experienced enrollment losses. Forty of these districts lost 10 percent of students or more. (Though not displayed below, the results are similar when FY 2010 is the baseline year—seventy districts lost enrollment—and about half saw enrollment declines if FY 2015 is the baseline.) Note that these enrollment changes were not affected by the pandemic-related declines seen in the FY 2021 data.

Figure 1: Enrollment trend among Ohio districts that do not participate in open enrollment, 2005–06 to 2019–20

Source: Ohio Department of Education, Open Enrollment and District Report Cards

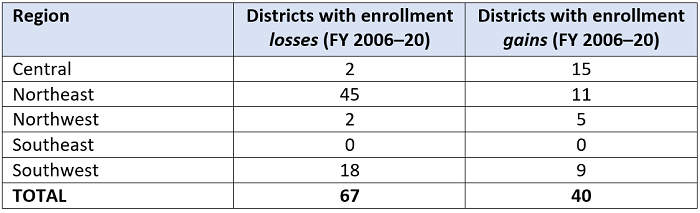

Following broader demographic trends within Ohio, most of the shrinking non-participating districts are located in northeast Ohio, while those gaining enrollment are in the fast-growing central Ohio suburbs around Columbus. Table 1 displays the data by region.

Table 1: Geographic analysis of districts that do not participate in open enrollment

Note: School districts were linked to a region based on the Ohio Department of Natural Resources’ division of the state.

Thus we see that most non-participating districts probably have excess capacity. There’s no good reason for these districts to refuse admission to non-resident students. Even the economics of open-enrolling students makes sense. The state provides an additional $6,020 for each student who open-enrolls (receiving districts may receive extra funds for students with disabilities). Because the district has capacity, the dollars tied to an additional student should cover the incremental costs of her education. True, a district may need to purchase another textbook or two, but its facility, administrative, and instructional costs wouldn’t rise significantly by filling an open seat. Airlines don’t turn away travelers when their planes are half-full. Schools shouldn’t either.

The story is more complicated for fast-growing districts. They are likely being stretched to meet the needs of resident students (though falling birthrates and shifting enrollment in the wake of the pandemic may soon yield excess capacity). Nevertheless, to address these outliers, state legislators should consider a capacity-based exemption in a switch to a mandatory open-enrollment system. But how should they design such an exemption? The capacity provisions from other states with mandatory open-enrollment laws offer a few ideas that could guide Ohio:

- Address capacity constraints at a school level. Utah law is an exemplar in the way it addresses capacity concerns within a mandatory open enrollment framework. Notably, its exemption is targeted at individual schools, only permitting districts to deny non-resident students if a particular school is at 90 percent of maximum capacity (see the next bullet point on how this term is defined). By focusing on the school level, non-resident students could attend an underutilized school within a district that otherwise has full classrooms.

- Clearly define “capacity.” Under Utah law, a school’s capacity is generally based on its district’s average class size times the number of classrooms in the building. For example, a school with fifteen classrooms and an average class size of twenty would yield a maximum capacity of 300. The specificity of Utah law is far superior to states such as Iowa, which leave capacity determinations up to school districts. The risk of such an approach is that districts may be less than truthful about their building capacities to avoid serving non-resident children.

- Include transparency provisions. To ensure that districts do not abuse an exemption, Ohio could follow the lead of states such as Minnesota and Florida, which include transparency measures in their open-enrollment laws. Minnesota requires a district that has been permitted to limit enrollment on capacity grounds to report the number of students denied admission. Florida gives districts broader leeway to determine capacity, but still requires them to post building capacities on their website. Such transparency provisions would allow the public to verify districts’ claims that they are “at capacity.”

It’s sad to see school districts with plenty of capacity refuse to open their doors to non-resident students. The reasons behind their refusals are not altogether clear (one suspects some form of “nimbyism” or worse), but closed districts actively deny thousands of Ohio students an opportunity to attend a school that better meets their needs. State lawmakers should step in to rectify this situation by requiring all districts with capacity in their schools to participate in open enrollment.