Under pressure from the school establishment and teachers unions, Ohio lawmakers recently filed bills that seek to cancel state assessments this spring. If enacted, the legislation would cancel exams (subject to a federal waiver) for a second straight year, leaving Ohioans in the dark about where students stand academically amid major disruptions to their education.

Recognizing the need for up-to-date information, influential civil rights and education groups have opposed calls to bypass assessments yet again. Political leaders of both parties have done the same. On the GOP side, then Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos told states last fall to be ready to give state exams this year. (Whether her successor will follow the same path is TBD.) Here in Ohio, Governor Mike DeWine and Senate President Matt Huffman have voiced support for assessment as a way of seeing where kids are academically. Meanwhile, the Democratic chairs of the U.S. Senate and House education committees, Senator Patty Murray and Representative Bobby Scott, called testing this spring “a moral imperative”:

In order for our nation to recover and rebuild from the pandemic, we must first understand the magnitude of learning loss that has impacted students across the country. That cannot happen without assessment data. … Today’s announcement [regarding NAEP] makes 2021 administration of statewide assessments required by federal law a moral imperative.

Given the bipartisan backing—and support among parents—one might be surprised to see the pushback on state assessment this spring. What arguments are opponents making, and do they hold water? The following distills the major objections and then addresses those concerns.

Objection 1: It’s been a tough year and schools deserve a free pass. The 2020–21 year has indeed been like none other, and schools have faced significant challenges serving students amid the pandemic. Recognizing this, Ohio legislators have already waived report card ratings and consequences for the current school year, as they did for the prior year. No district or school will be penalized for its spring 2021 assessment results. All that’s being asked is that this year’s state tests be administered, so that parents and the public can see where students stand—a basic measure of transparency that will shine light on pupil achievement and help to guide recovery efforts.

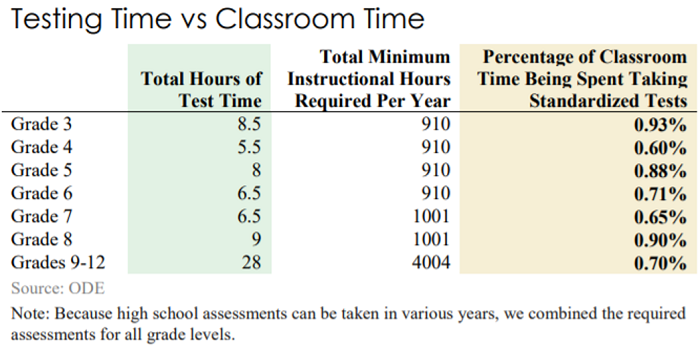

Objection 2: It’ll take away instructional time. Too much time on assessment is a common criticism even in normal circumstances. But opponents are ratcheting up their demands, arguing that zero time on testing is appropriate this year. To understand why this argument is flawed, it’s important to consider the facts about how much time is spent on state exams. The following table, taken from a recent report by the Auditor of State, reveals that students spend less than 1 percent of a school year on state exams. Of course, one might argue that thanks to remote learning, students may have received less than the typical 900 to 1,000 hours of instructional time this year. But it must be emphasized that the state did not waive its minimum hours requirement. During the pandemic, schools have been expected to make good faith efforts to meet them.

Objection 3: Diagnostic assessments are enough. In response to the argument that state exams are needed to gauge where students stand, opponents have put forward the notion that the diagnostic tests that many districts use are sufficient. These tests, such as the MAP and iReady, are of course important to educators. They offer a rapid assessment of student learning that allows teachers to tailor instruction and make course corrections during a school year. But diagnostic tests have significant limitations:

- Schools have no obligation to publicly disclose diagnostic test results. Yes, a few schools may voluntarily choose to report these data—perhaps in response to public or media pressure—but most are likely to keep those results internal and out of public sight.

- Most diagnostic tests are created by national assessment vendors and may not be linked to state academic standards. (Most notably, the tests don’t assess writing.) Ohio educators helped create the state’s English and math standards, which help ensure that all students are challenged to meet grade-level expectations. State exams are closely tied to these standards and offer clear information about whether students are achieving state goals.

- Diagnostic exams don’t yield comparable information, allowing achievement gaps to be swept under the rug. Without uniform data, no one will know whether gaps between Ohio’s low-income or special-education students and their peers have widened as a result of the pandemic. The ability to hide achievement gaps is one reason why civil rights and disability groups have been so adamant that statewide assessment occur this year.

Objection 4: We already “know” the results. Some opponents of testing this year have claimed that it’s unnecessary because we already know the results. On average, it’s almost surely true that the typical student has suffered losses due to the disruptions. The averages, however, mask significant variation in the learning experiences—and outcomes—of students. Consider the recently released data from Ohio’s fall third grade ELA assessments. While the average third grade test score fell significantly, we also see that eighty-four districts and charter schools posted higher proficiency rates in fall 2020 versus the previous fall.[1] Twenty-eight of these schools had economically disadvantaged rates of more than 50 percent—bucking the conventional wisdom that low-income students are destined to lose ground. Meanwhile, among the eighty-eight districts and charters where proficiency rates slid more than 20 percentage points, twelve of them had had economically disadvantaged rates of less than 25 percent.

At the end of the day, no one truly knows how districts, schools, or students have fared over the past year. The danger of making policies or decisions based on assumptions about who is doing well or poorly is that students won’t be served well. Some may be consigned to remediation when they are actually ready to zoom ahead. Conversely, children struggling academically may get overlooked, allowing them to fall through the cracks. To ensure that decisions aren’t being made based on false assumptions, we need data about where each student stands against state academic standards.

* * *

With teachers being vaccinated and all schools expected to return to in-person instruction in March, there is no good reason to waive state exams for another year. High stakes won’t be involved in this round of assessment, schools should have ample time to administer them, and the results will provide information that cannot be achieved through local testing. Ohio should begin its “return to normalcy” with solid baseline information about student achievement in the midst of much turmoil.

[1] To be included in this count, a district or charter school needed to have at least twenty test takers and at least 66 percent of the number of test takers in fall 2020 versus fall 2019. This was done in an effort to remove schools with low test participation rates in fall 2020.