Pensions, a promise of guaranteed lifetime income for retirees, have been around since antiquity. No other than Caesar Augustus is said to have created a pension fund for army veterans. Expanding far beyond the military, today’s pension systems cover some private sector employees and large swaths of government workers, including public school teachers. In 1911, Massachusetts opened the nation’s first teacher pension; Ohio founded the State Teachers Retirement System (STRS) in 1920 to administer pensions.

Traditional pensions have grown to almost mythical status in the public sector, billed by proponents as a gratuity for a career of service and a recruitment tool. But behind the legend stands a messier reality. In a prior analysis, I looked at the massive costs of pensions to Ohio teachers and schools. This piece looks at three additional problems that plague the system.

1. Snubbing teachers who leave “too early”

Early and mid-career teachers lose significant retirement wealth if they choose to separate from the system, whether to take teaching positions outside of Ohio, pursue other career opportunities, or take care of children at home. Consider what happens to short- and medium-tenure teachers.

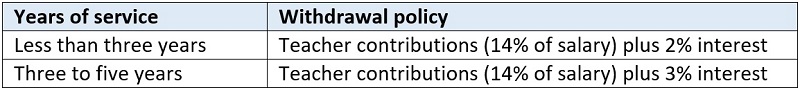

Short-tenure teachers: Individuals who teach less than five years are not entitled to a pension—they’re not “vested”—but are allowed to withdraw funds they’ve contributed when they exit. The table below shows the rules.

Table 1: Withdrawal rules for non-vested teachers

Source: STRS, Comprehensive Annual Financial Report, 2021 (p. 74)

At face value, this doesn’t look so bad. But remember that STRS requires contributions from both teachers and their employers to fund retirement benefits—a rate of 14 percent of salary, each. What’s missing is the employer contribution. Short-term teachers don’t get any of that money—it instead goes to help pay other people’s retirements. Some may argue that a teacher shouldn’t be entitled to that portion, but it doesn’t the change the fact that retirement dollars generated by the teacher’s salary—and her work—are being diverted elsewhere.

The money lost is significant. For a teacher with four years of service and earns $150,000 in total salary, the employer share adds up to $21,000. If she put those dollars in a IRA yielding 5 percent annually, she would have more than $90,000 in thirty years.

Medium-tenure teachers: Those who teach longer—but not to retirement age—may opt to receive pension benefits (lifetime payments) or withdraw their funds. Unfortunately, the system also shortchanges these teachers, some of whom work a decade or two in the classroom.

A trifecta of policies hurt mid-career teachers who opt for the pension option. First, the value of a pension hinges on a worker’s final average salary before exiting the system. But because mid-career teachers are lower on the seniority-driven salary schedule, their retirement benefits will be rather modest to begin with. Second, their final average salary isn’t indexed for inflation, a greater issue for early leavers who must wait to collect benefits for twenty or thirty years into the future. Think of it this way: A medium-tenure teacher who is retired today could be receiving benefits based on earnings from twenty or thirty years ago—a salary that has long been eroded by inflation. This is less of an issue for full-career retirees, whose final salaries are from more recent years. Third, medium-tenure teachers aren’t eligible for payments until age 65, an older age than when most teachers meeting the full retirement criteria start collecting benefits (mid 50s to early 60s). Delaying benefits reduces the value of the pension, as teachers receive fewer years of payouts.

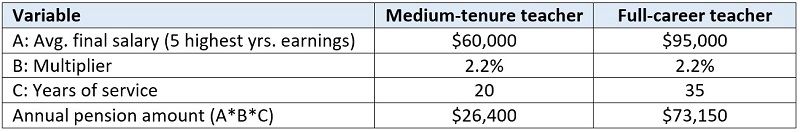

As a result of these policies, teachers separating “too early” receive benefits that are not commensurate to their contributions to the pension system and work in the classroom. Table 2 illustrates the meager benefits that a teacher with twenty years of experience would expect to receive if she left STRS. Remember that Ohio teachers are not in Social Security, so they rely more heavily on their pension.

Table 2: Illustration of pension amounts for medium-tenure versus full-career teacher

Calculations are based on the pension formula stated in STRS, Comprehensive Annual Financial Report, 2021 (p. 73).

Medium-tenure teachers electing for a lump-sum withdrawal also pay a price. While they get 1.5 times their own contributions refunded (plus 3 percent interest), they don’t receive the employer contribution. For early leavers whose employee-employer contribution rate was 14 percent each, they effectively sacrifice half of their employer contribution (7 percent). Thus, a teacher with two decades of experience and total earnings of $900,000 would forfeit $63,000 in employer contributions.

Economist Robert Costrell writes, “Most teachers earn little or no employer-funded benefit if they leave before about age 50. The employer contributions made on their behalf help fund the benefits of those who stay longer. This is intra-generational redistribution.” Calling this system “redistribution” is almost too polite. What it does is rob Peter to pay Paul. In so doing, it cheapens the work of young teachers on behalf of students.

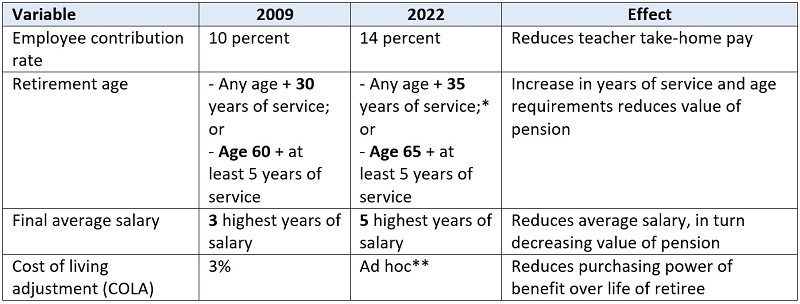

2. Exposing career teachers to financial pain

Career-teachers who reach retirement age do reap better benefits than their unfortunate counterparts. But even for them, the system is not entirely free of risk. Though pensions guarantee lifetime income, it doesn’t shield them from policy changes that reduce their wealth. Consider the table below, which shows changes in STRS’s pension rules. First, note that the employee contribution rate has risen significantly in the past decade, cutting teachers’ take-home pay. Yet despite the higher costs, benefits haven’t risen. They’ve actually been cut. In 2009, for example, teachers needed thirty years of service to retire and receive benefits right away. Teachers will soon need thirty-five years of service, an elongated period that reduces the value of the pension. For instance, raising the service requirement by five years costs a retiree $250,000 in pension value if it’s worth $50,000 per year. Meanwhile, the suspension of cost-of-living-adjustments (COLAs) starting in 2017 has infuriated retirees, especially now that inflation is through the roof, and STRS only recently reinstated a one-time adjustment. In a recent interview, one teacher aptly summed up the situation: “I am working longer and getting less money for it.... It is criminal.”

Table 3: Changes in STRS policy between 2009 and 2022

Sources: STRS Comprehensive Annual Financial Reports and Chad Aldeman, Default Settings. * The increase to 35 years of service is being phased-in and will apply first to teachers retiring after 2023. ** STRS suspended COLAs starting in 2017, but it recently provided a 3 percent, one-time adjustment for 2022.

3. Taking massive investment risks to cover funding gaps

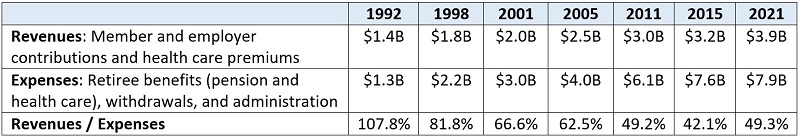

Over the years, STRS has needed to rely more heavily on investment income—not simply contributions from workers and employers—to fund retiree pensions. Table 4 shows that, in 1992, the system took in more than it paid out. But starting in the late 1990s, the picture rapidly shifted, with the growth in outlays far outpacing revenues. Today, annual contributions fall billions short of the amounts paid to retirees.

Table 4: STRS revenues (less investment income) versus expenses, selected years

Source: Ohio Retirement Study Council, STRS Comprehensive Annual Financial Reports.

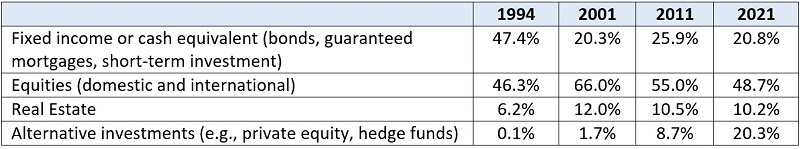

To cover the escalating costs, STRS has several options. It could require higher teacher or district contributions, it could ask legislators for more funds, or it could cover expenses by pursuing large investment returns. Indeed, STRS bets big on investments, as have other pension systems in Ohio and around the country. Table 5 shows that STRS’s portfolio has shifted away from safer investments to equites, real estate, and alternative investments. While those instruments can yield strong returns in years of plenty, they are also riskier than treasuries or cash equivalents. As occurred during the Great Recession, a risk-taking portfolio can lead to huge losses and massive increases in a pension’s unfunded liabilities (equites, real estate, and alternatives all slid during 2008 and 2009).

Table 5: STRS’s investment portfolio, selected years

To be clear, there is nothing inherently wrong with individuals putting their own money into stocks or private equity. They reap the benefits or bear the consequences. The problem with inordinate risk in this context is that pensions guarantee benefits to retirees. If stocks tank or a hedge fund collapses, STRS can’t—and shouldn’t—stop making payments or cut benefits to the bone. Someone, either teachers or taxpayers, will have to cover the costs.

The misalignment between immutable pension obligations and uncertain investment returns is one reason why some experts recommend that pensions reduce their assumed rate of return—STRS’s is currently 7 percent—and pursue more conservative strategies. The policy dilemma, however, is that reducing the discount rate would increase unfunded liabilities, which in the case of STRS is already at $21 billion.

***

Far from being the Rock of Gibraltar on which teachers can build their retirement dreams, Ohio’s pension system is more akin to a house of cards that imperils teacher and taxpayer money and pickpockets short- and medium-term educators in a cruel effort to make ends meet. Of course, STRS isn’t alone in the national pension nightmare. As Josh McGee writes:

[Public retirement plans] are bigger and riskier than ever before, and their growing annual cost is crowding out spending in important areas like public safety and education. Public workers bear a significant share of increased pension cost through stagnant wages, benefit reductions, and worsening job conditions. And many jurisdictions are not prepared for the next major economic downturn.

The question now is whether Ohio policymakers are willing to make the hard choices that can create a fairer, more fiscally sound retirement system, one that ensures all teachers—from young to old—receive the hard-earned benefits they deserve.