School choice and parental empowerment are among the hottest topics in education these days. Here in Ohio, state lawmakers are actively discussing proposals that would strengthen private school choice and public charter schools. One topic that doesn’t get as much attention is interdistrict open enrollment, one of Ohio’s oldest and most popular choice programs. As we’ll see in this piece, lawmakers still have room to improve this program by making it accessible to more students.

Under this policy, students are allowed to attend public schools in a neighboring district, tuition-free. This opens up significant possibilities: Students can attend schools that offer special academic or extracurricular programs that aren’t available in their home district. It can allow them to attend a school with close companions or one that is closer to their home. For students from less advantaged communities, open enrollment can increase access to higher-quality schools located in their vicinity—schools that tend to be more racially and socioeconomically diverse, as well.

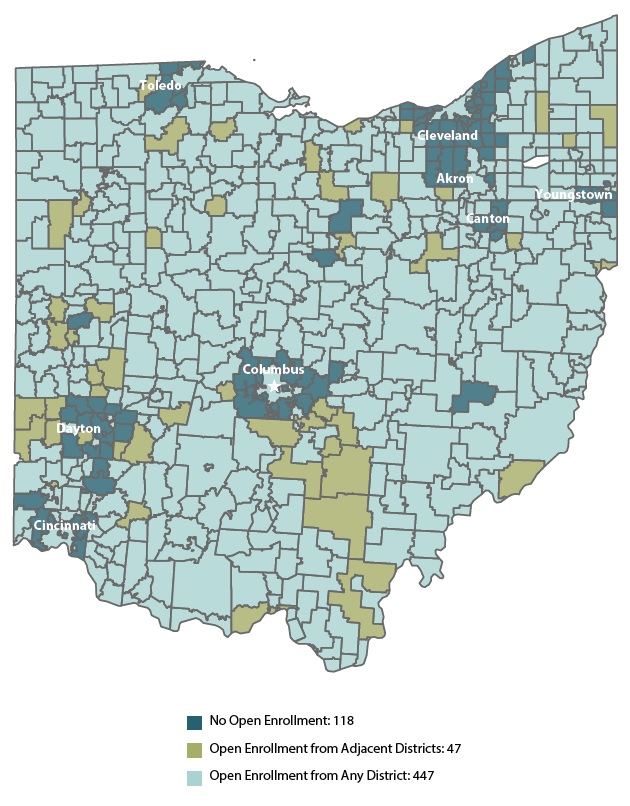

To their credit, a large majority of Ohio districts allow non-resident students to open-enroll, and approximately 80,000 students avail themselves of this opportunity. But—as permitted under Ohio’s voluntary participation policy—about one in six districts forbid open enrollment. They choose to close their doors to outsiders, allowing only children who reside in the district to attend their schools. As the figure here shows, refusing districts (shaded in dark blue) are located almost exclusively around Ohio’s largest cities. This map is based on 2018 district participation in open enrollment, but the pattern continues today. These suburban districts are overwhelmingly White and affluent, while the center-city districts are overwhelmingly Black and poor. Some might say that this is what systemic racism looks like; at the least, it’s a form of “educational redlining.”

We at Fordham and others have argued that state law should require all districts to participate in open enrollment. This would unlock options for more Ohio students, especially children who live in urban areas and lack district-run options other than those provided by their home district. It would also allow more suburban students to transfer from one district to another, without having to pick up and move.

Yet one commonly heard objection to such a requirement is that districts don’t have the physical space to serve more students. That’s a fair concern, and legislators would be smart to include a capacity waiver provision in a switch to mandatory participation.

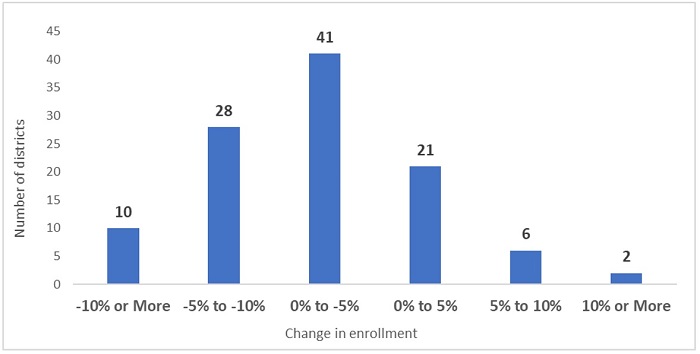

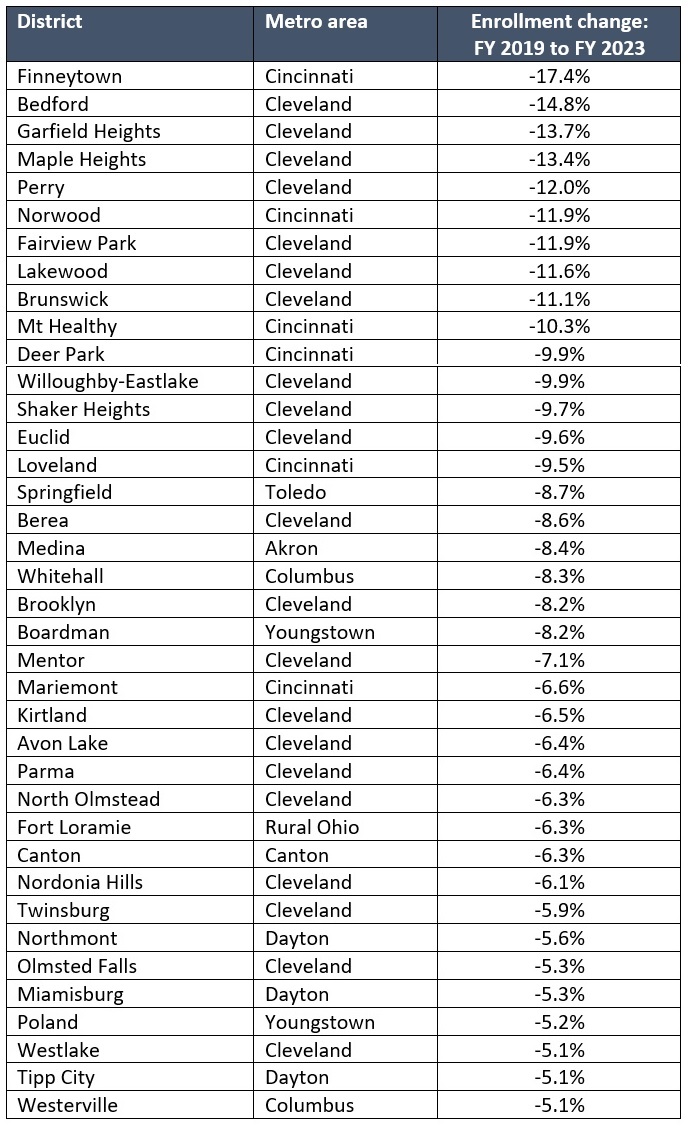

But it’s also important to understand that this objection doesn’t apply in most cases. Consider the data shown in Figure 1. Of the 108 districts that aren’t accepting open enrollees this year, 79 of them have experienced enrollment losses from 2018–19 to 2022–23. In 38 of these districts, the declines are fairly steep (more than 5 percent). As Table 1 indicates, most of these rapidly shrinking districts are located in Northeast Ohio, a region that has experienced flat to declining general population trends. In the Cleveland area, for instance, Bedford, Garfield Heights, and Maple Heights school districts have all experienced enrollment losses of more than 13 percent since 2018–19. Surely, districts such as these have room in the inn.

Figure 1: Change in enrollment among non-participating districts from 2018–19 to 2022–23

Table 1: Non-participating districts with declines of more than 5 percent from 2018–19 to 2022–23

* * *

Districts with declining enrollments have no excuse for refusing students who want to attend their schools. Financial implications shouldn’t be a deal-breaker, either, as the state provides per-pupil funding that should cover the incremental cost of educating additional students. While the district may have increased expenses for items such as textbooks and supplies for open enrollees, it won’t need to spend significantly more on facilities or teacher salaries when they fill empty seats. Those types of fixed costs are already paid for. In fact, operating closer to capacity would not only benefit students, but could also achieve efficiencies that allow districts to stay off the local levy ballot.

Public schools should be “open to all.” By denying access based on a student’s zip code and requiring parents to purchase housing in their districts to attend, non-participating districts continue to defy that principle. State lawmakers should finally step in to address the nonsensical refusal of certain districts to serve Ohio students.