Politicians are notorious for handing out subsidies for certain projects and sectors of the economy. These goodies help them stay in power and appease special interests. But as Chris Edwards of the Cato Institute argues, they also create an uneven playing field in which legislators pick winners and losers at taxpayer expense. Unfortunately, Ohio’s new funding system isn’t immune to this pork-barrel practice. This piece looks at two special subsidies—one favoring small districts and the other larger, urban ones—that are baked into the new funding model. Legislators should reevaluate the need for both as they review the new formula in the coming months.

Small district subsidy via staffing guarantees

In last year’s overhaul of the formula, Ohio lawmakers created a new set of calculations that attempt to “cost out” what it takes to educate a typical student. To do this, the model relies on staff-to-pupil ratios, average employee salaries and benefits, and spending on other educational “inputs.” The computations produce a base cost for each district, which is then used in conjunction with a measure of property and income wealth to determine the bulk of state aid that districts receive. The basic equation is as follows:

That’s a lot to digest. But the key things to know for the purposes of this analysis are: (1) the base-cost per pupil is a critical factor in determining a district’s state funding and (2) the new formula yields variable bases that differ across Ohio’s 600-plus school districts. The latter is a significant turn from the previous formula which set a fixed base that applied to all districts, most recently $6,020 per pupil.

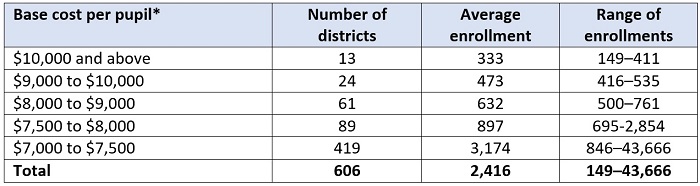

Table 1 shows a breakdown of base cost per pupil across Ohio districts. Most districts—roughly two in three—have bases within a narrow range of $7,000 to $7,500 per pupil. But a number of districts have higher amounts. Thirteen have bases above a whopping $10,000 per pupil—and all of them are teeny-tiny districts with enrollments ranging between 149 and 411 students. The next highest tier of base costs—$9,000 to $10,000—also consists of small districts with only slightly higher enrollments (average of 473). Only when we pass about 1,000 students in a district do the base costs settle into the more “normal” range.

Table 1: Ohio school districts’ base costs, FY 2022

* The statewide average base cost is $7,349 per pupil. While not included in this table, charter schools’ base-cost model is somewhat different and yields an average base of $7,337, with a range of $6,824 to $8,586 per pupil. Due to the phase-in of the HB 110 funding model, districts and charters are not actually being funded at these base amounts in FYs 2022–23 (these would be the amounts under a fully-funded formula). Source: Ohio Department of Education, Foundation Funding Report (FY 22 May #2 payment file).

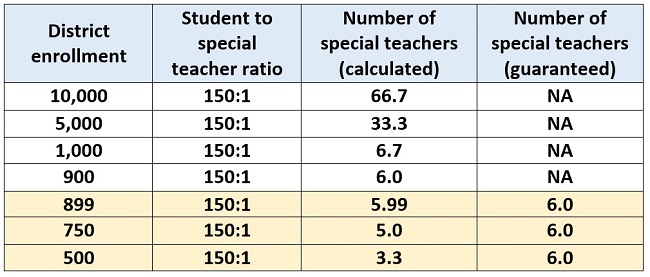

What is causing this escalation in base costs? It’s actually due to a mechanical quirk in the base-cost model. As mentioned above, this model relies on student-to-staff ratios to determine the number of employees assumed to be needed—and thus “costed out”—in a district. Things get interesting, however, due to a policy that guarantees a minimum number of employees in certain staff positions. Table 2 shows how the minimum plays out for the “special teachers” (e.g., arts, music, and PE) portion of the base-cost model. Districts with more than 900 students are prescribed special teachers strictly by ratio (150:1). But those with enrollments under this threshold receive more teachers (six) than what the formula otherwise prescribes.

The upshot: The staffing minimums increase the per-pupil base costs for Ohio’s smallest districts—they are, for formula purposes, “overstaffed”—which in turn, inflate their state funding.[1] By my ballpark estimation, the minimums would cost the state roughly $150 million to $200 million per year under a fully implemented formula, or about 2 percent of the state’s annual funding for K–12 education.

Table 2: How the special-teacher staffing minimum works

The staffing minimums give Ohio’s smallest districts—though interestingly, not charter schools, which serve comparable numbers of students—special treatment through the base-cost model. Some may argue that small districts face higher costs due to lack of scale. But there are ways that districts can operate cost-effectively. One possibility, strongly encouraged back in 2012 by the Kasich Administration, is to share services and personnel. Small districts, for example, could team up to share art and music teachers or administrative and maintenance staff. Some districts, in fact, already do this: Cloverleaf and Medina, for instance, share a treasurer. Districts could also leverage regional educational service centers, joint-vocational districts, or institutions of higher education to provide special programming, college and workforce counseling, or back-office support.

In the end, no district has to go it alone. Opportunities abound to build scale without sacrificing—and perhaps even enhancing—educational quality. Districts also don’t have to do this through consolidation; this can all be done organically and voluntarily without losing local autonomy. Unfortunately, the formula’s small-district subsidy—buried deep within the base-cost model—discourages cost-effective problem solving that can benefit both taxpayers and students. Moving forward, legislators should remove this special subsidy by eliminating the staffing minimums from the base-cost formula. All districts’ base costs—and charters’ too—should be calculated in the same manner. In a formula touted as the “fair school funding plan,” that’s only fair.

Urban district subsidy via “supplemental targeted assistance”

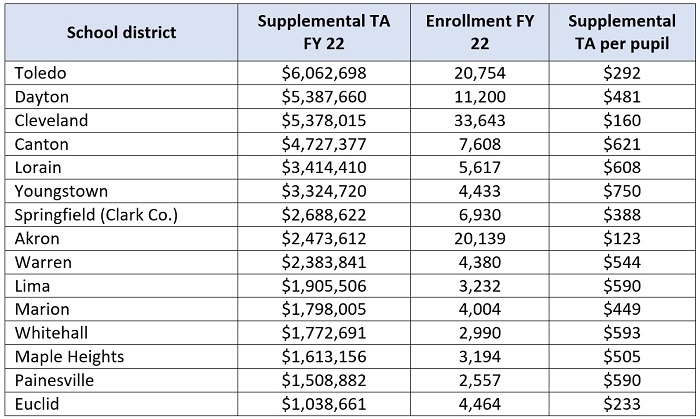

Ohio’s smallest districts aren’t the only beneficiaries of an extra subsidy that deviates from formula calculations. Also hidden in the funding system is a new $54 million per year outlay called supplemental targeted assistance. If a district had a sizeable proportion of students in choice programs and was relatively poor in FY 2019, it receives these funds. Based on these parameters, just thirty-six districts got the extra funding. Table 3 displays the districts that received more than $1 million in supplemental targeted assistance in FY 2022. Taken together, these fifteen districts—largely big-city and inner-ring urbans—collected 84 percent of the total subsidy ($45.5 million). Note that much like the staffing guarantees, charters are not eligible for these dollars.

Table 3: Districts receiving the most supplemental targeted assistance (TA) in FY 2022

Source: Ohio Department of Education, Foundation Funding Report (FY 22 May #2 payment file).

Though not an enormous amount, the dollars funneled through this component are another unnecessary subsidy, this time propping up urban districts that have historically “lost” significant numbers of students to choice programs. It’s clearly not formula-driven funding; it’s not at all tied to a district’s current enrollments and wealth. Instead, it looks back on old data to provide excess dollars to an extremely narrow group of districts (just 6 percent of them). Maybe legislators intended it to be a “payoff” to districts that have long bemoaned the transfer of state funds to students’ schools of choice. If that’s the aim, it sure isn’t working. Toledo Public Schools—the largest beneficiary of the subsidy in absolute dollars—recently joined the lawsuit against EdChoice (perhaps using these funds!).

Now, sending extra funds to select districts—ones getting strong results for kids—would make perfect sense in a performance-based funding component. But that’s hardly the case here. In fact, one could view it as a bizarre reward for districts that have fared poorly in meeting the needs of resident families. And while many of these districts are high-poverty, that is addressed through the other mechanisms in the formula, including—as noted above—the “state share percentage,” which ensures that more state aid is steered to poorer districts, along with a large funding bucket based on economically disadvantaged student counts. In sum, this funding stream sends extra dollars—more than what the formula prescribes—to a small number of districts for reasons that simply don’t make good sense.

***

The proponents of the HB 110 model regularly argued last year that a school funding formula should treat all districts fairly—without favoring certain ones over others. And they’re right. But the current formula doesn’t quite achieve the promised goal due to the special carveouts discussed here. As legislators consider whether to fully fund this system as is or make changes to it, they should work to ensure that all schools receive dollars under an evenhanded formula.

[1] In addition to the special-teachers minimum, districts are guaranteed at least five student-wellness-and-success staff, two district administrators, two fiscal-support staff, one high school counselor, one superintendent, one treasurer, one EMIS staff, one administrative assistant, and one school-level clerical staff.