In its biennial budget plan for FYs 2024–25, the Senate—as did the House—proposed a hefty increase in K–12 education spending. Despite the overall largesse, the Senate also proposed the elimination of a funding category called “supplemental targeted assistance.” The idea raised some eyebrows among education groups, as any type of reduction—no matter how small—is rarer than a blizzard in June. The proposal could easily become a point of debate in conference committee. But what is this funding component and why should it be removed?

Simply put, these dollars are “pork.” First appearing in FY22, the component funnels $53.4 million to just thirty-six of Ohio’s 600 plus districts. To receive the special subsidy, districts must have been relatively low wealth in the state’s formula calculations and had a sizeable number of students attending non-district schools in 2019. As we all know, a lot has changed since 2019, and using historical data is the wrong way to allocate state aid. These funds aren’t tied to districts’ actual enrollments or the needs of current pupils, which are the variables that truly matter when funding schools. But somehow these districts got a special carve-out—something of a “reward” for having families exit their schools—and now receive millions in excess funding.

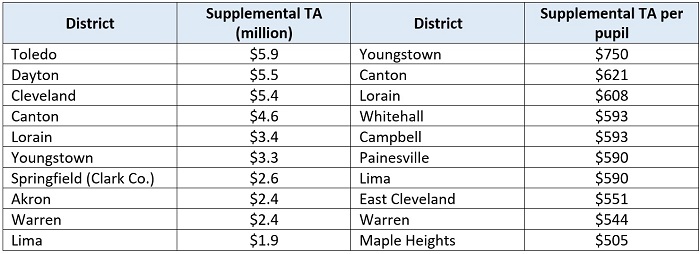

The table below shows the largest beneficiaries of these funds. In absolute dollars, Toledo Public Schools receives the most supplemental targeted assistance ($5.9 million per year), while Youngstown City Schools receives the largest allotment on a per-pupil basis ($750).

Table 1: Districts receiving the most supplemental targeted assistance (TA) in FY23

Some may argue that eliminating these funds is cruel or heartless. One superintendent told the Senate Finance Committee that losing these dollars would be “devastating.” But let’s keep four things in mind.

First, while a less-than-ideal policy, the Senate budget plan does guarantee that districts receive no less in state aid than they did in FY23.[1] Even if supplemental targeted assistance goes away, these districts won’t actually have their overall state aid cut; they’d just receive a smaller increase.

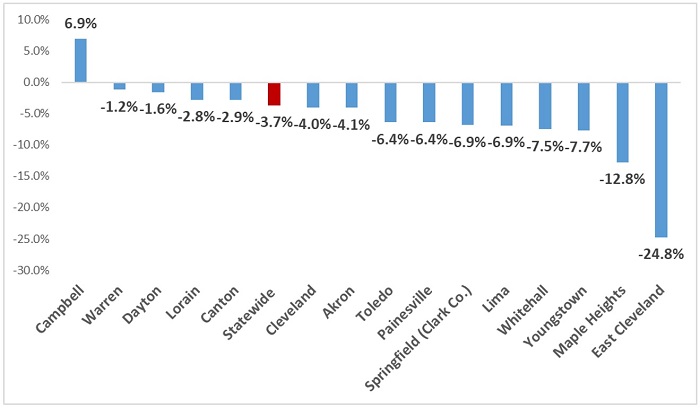

Second, most districts receiving these dollars have lost significant numbers of students in recent years. Figure 1 shows the enrollment patterns from FY20–23 for the ten largest recipients of supplemental targeted assistance, whether in absolute or per-pupil dollars. Districts, including Whitehall and Youngstown, posted enrollment losses that more than double the statewide average during this period. East Cleveland’s enrollment dropped by a stunning 25 percent in just four years. When schools are responsible for serving fewer students, especially at these rates, their educational costs should decrease, as well. How do these districts justify the need for excess state aid on top of what they already receive through the formula?

Figure 1: Change in enrollment from FY20 to FY23, largest recipients of supplemental TA

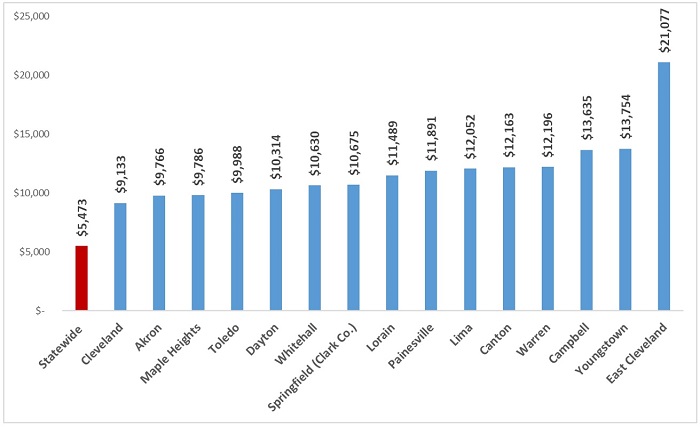

Third, districts receiving supplemental targeted assistance already receive far more in state aid than the typical Ohio district. To be clear, some of that is justified, as the funding formula intentionally drives more aid to the least-advantaged districts—and those receiving these dollars tend to be disadvantaged. But some of the state funding amounts are still quite large, even with the elimination of supplemental targeted assistance. Consider Figure 2 below, which shows funding projections under the Senate plan. Districts such as Dayton, Springfield, Lorain, Canton, and Youngstown are slated to receive $10,000 to $14,000 per pupil in state foundation funding under the Senate plan. East Cleveland could end up receiving a staggering $21,000 per pupil. Remember that this is strictly state formula funding. It doesn’t even include the millions more in local funding that districts raise (including via a minimum state-required 2 percent property tax).

Figure 2: Projected state foundation aid per pupil, Senate plan (FY 2025)

Fourth, if the concern is to deliver more dollars to high-poverty schools, there are better ways to do it. Instead of shoveling money to a small number of districts—thereby excluding other high-poverty districts, such as Cincinnati and Columbus, as well as urban public charter schools—lawmakers could work to strengthen Disadvantaged Pupil Impact Aid (DPIA). This funding component delivers extra state funds to all districts and charters based on their economically disadvantaged enrollment numbers. While it’s too late in this budget to address, legislators should take steps in the future to improve DPIA by implementing a methodology that more accurately identifies low-income students. This will better ensure state aid is steered to the schools that most need the extra resources in the fairest way possible. Once a more accurate identification method is adopted, legislators could consider further increasing DPIA funding.

* * *

Removing “guarantees,” carve-outs, and special earmarks from government budgets isn’t easy political work. It’s bound to upset someone. But sometimes legislators have to put an end to them. Kudos to Senate lawmakers for seeking to root out inefficient and unnecessary spending in K–12 education. Let’s hope its proposal to scrap supplemental targeted assistance sticks.

[1] The Senate does, however, commendably eliminate funding guarantees based on historic FY20 and FY21 funding levels, in addition to eliminating supplemental targeted assistance.