NOTE: Today, the state board of education heard public comment on a pending resolution which would call for the elimination of the retention provision of Ohio’s Third Grade Reading Guarantee. Below are the written remarks given by Chad L. Aldis, Fordham’s vice president for Ohio policy at that meeting.

Thank you, President Maguire, Vice President Manchester, and State Board members for the opportunity to provide public comment on the resolution calling for the elimination of the retention requirement for third graders who cannot meet the state’s promotion threshold.

My name is Chad Aldis, and I am the vice president for Ohio policy at the Thomas B. Fordham Institute. The Fordham Institute is an education-focused nonprofit that conducts research, analysis, and policy advocacy with offices in Columbus, Dayton, and Washington, D.C.

Reading is absolutely essential for functioning in today’s society. Job applications, financial documents, and instruction manuals all require basic literacy. And all of our lives are greatly enriched when we can effortlessly read novels, magazines, and the daily papers. Unfortunately, even today, roughly 43 million American adults—about one in five—have poor reading skills. Of those, 16 million are functionally illiterate.

Giving children foundational reading skills, so they can be strong, lifelong readers, is job number one for elementary schools. Understanding this, Ohio passed the Third Grade Reading Guarantee in 2012. The law’s aim is to ensure that all children read fluently by the end of third grade—often considered the point when students transition from “learning to read” to “reading to learn.”

The Guarantee takes a multi-faceted approach. It calls for annual diagnostic testing in grades K-3 to screen for reading deficiencies and requires reading improvement plans and parental notification for any child struggling to read. Importantly, it also requires schools to hold back third graders who do not meet state reading standards and to provide them with additional time and supports.

I urge the State Board to reconsider its recommendation to eliminate the guarantee’s retention requirement.

Why retention?

The goal of retention is to slow the grade-promotion process and give struggling readers more time and supports. When students are rushed through without the knowledge and skills needed for the next step, they pay the price later in life. As they become older, many of them will decide that school is not worth the frustration and make the decision to drop out.

An influential national study from the Annie E. Casey Foundation found that third graders who did not read proficiently were four times more likely to drop out of high school. A longitudinal analysis using Ohio data on third graders found strikingly similar results. The consequences of dropping out are well-documented: higher rates of unemployment, lower lifetime wages, and an increased likelihood of being involved in the criminal justice system.

Seeing data such as these, almost everyone agrees today that early interventions are critical to getting children on-track before it’s too late.

Some believe that schools will retain children without a state requirement. Anything’s possible, but data prior to the Reading Guarantee makes clear that retention was exceedingly rare in Ohio. From 2000 to 2010, schools retained less than 1.5 percent of third graders. Retention has become more common under the guarantee, as about 5 percent of third graders were held back in 2018-19.

In 2021-22, however, Ohio temporarily waived the promotion requirements and we saw a return to social promotion. Schools promoted virtually every third grader to fourth grade, whether they could read fluently or not; in fact, 100 percent of third graders were promoted in 469 out of 605 districts. At the same time, we also know that 20 percent of Ohio’s third graders have serious reading difficulties, having scored “limited”—the lowest achievement level on state exams. Students at this level earned less than 11 out of 40 possible points on their third grade ELA exam.

Make no mistake, if the legislature follows your advice and removes the retention requirement, Ohio will in all likelihood revert to “social promotion.” Students will be moved to the next grade even if they cannot read proficiently and are unprepared for the more difficult material that comes next. There’ll be relief in the short-run but the price in the long-term will be significant.

Data and research

Shifting gears, I’d like to briefly address two claims that regularly come up in Ohio when the topic is retention.

First, some have claimed—based on research studies—that holding back students can have adverse impacts. There is some debate in academic circles about how to assess the impacts of retention. Doing a gold-standard “experiment” with a proper control group is not possible in this situation, so scholars rely on statistical methods that help make apples-to-apples comparisons between similar children. But unless researchers use very careful methods, the results don’t give us much insight.

Arguably, the best available evidence on third-grade retention—as opposed to retention generally—comes from Florida, which has a similar policy to Ohio’s reading guarantee. That analysis, which compared extremely similar students on both sides of the state’s retention threshold, found increased achievement for retained third graders on math and reading exams in the years after being held back. It also found that retained third graders were less likely to need remedial high school coursework and posted higher GPAs. The analysis found no effect, either positively or negatively, on graduation.

If you would like to review this research for yourself, an essay on the findings by Harvard University’s Martin West, who led the Florida study, was published by the Brookings Institution in 2012. The longer, academic report was published by the National Bureau of Economic Research and in the Journal of Public Economics in 2017.

The second claim, particular to Ohio, is that the reading guarantee isn’t producing the improvements we’d like to see. The basis is a paper from The Ohio State University’s Crane Center that notes flat fourth grade reading scores on the National Assessment of Educational Progress from 2013-17. NAEP does offer a useful high-level overview of achievement, but raw trend data are not causal evidence about the impact of the third grade reading guarantee—or any other particular program or policy. The patterns could be related to any number of factors that affect student performance, whether economic conditions, demographic shifts, school funding levels, and much more. Without any statistical controls, it’s impossible to isolate the effect of the reading guarantee.

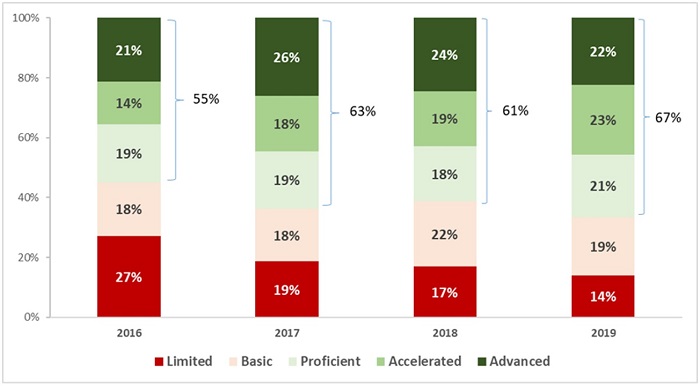

Of course, NAEP isn’t the only yardstick. It’s also worth considering what state testing data show. The chart below shows third grade ELA scores in Ohio. We see an uptick in proficiency rates—from 55 percent in 2015-16 to 67 percent in 2018-19. Also noteworthy, given the guarantee’s focus on struggling readers, is the substantial decline in students scoring at the lowest achievement level. Twenty-seven percent of Ohio third graders performed at the limited level in 2015-16, while roughly half that percentage did so in 2018-19.

I’d like to pause and emphasize this point. From 2016 to 2019, the percent of students reading at the lowest level was cut in half. Much of the data in the resolution focuses on proficiency, and I understand the inclination to do that. Ohio’s policy has been focused on getting students from “limited” into the middle of “basic” where the promotion score has been. And that is exactly what Ohio teachers and students appear to have done.

Ohio’s third grade ELA scores, 2015-16 to 2018-19

Much like NAEP trends, this shouldn’t be construed as causal evidence. But the improvements on third grade state exams should be weighed heavily in any analysis on whether the guarantee is improving literacy across Ohio.

Right now, no rigorous evaluation of Ohio’s Third Grade Reading Guarantee and the retention requirement has been conducted; however, the structure of Ohio’s law and the strong data system in place lends itself to a high quality research design. We encourage the State Board to take a step back and request that the department conduct a study on this issue before recommending that the retention requirement be eliminated.

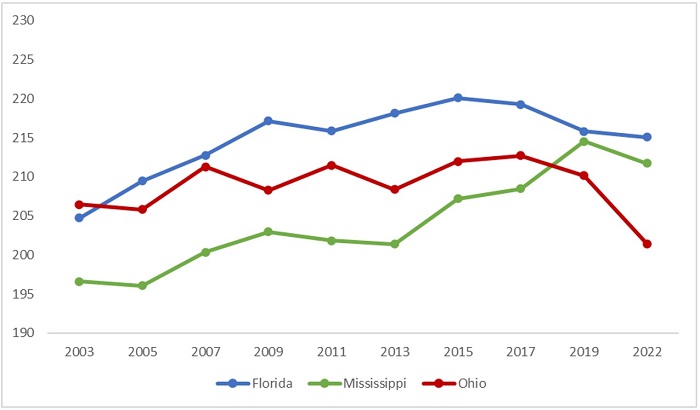

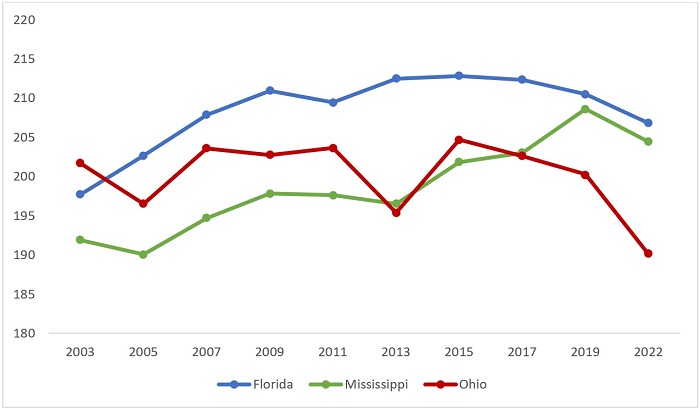

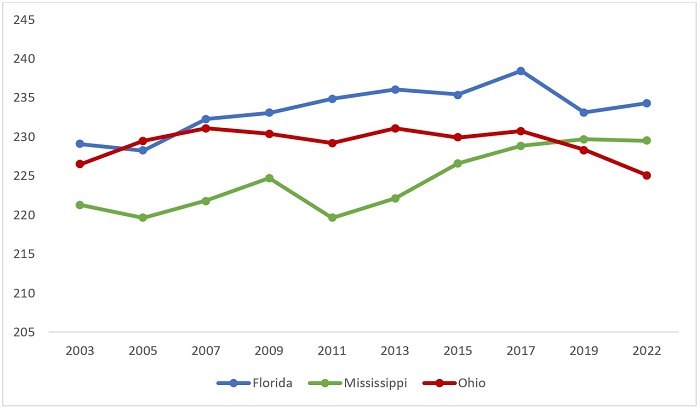

As I noted earlier, NAEP data is useful but not causal. If your inclination is to stick with NAEP though, you should look closely at what’s happened in Florida and Mississippi. Both states rigorously implemented comprehensive early literacy policies, including a third grade retention policy, and have enjoyed tremendous success.

NAEP scores in fourth grade reading, students eligible for free and reduced price lunch

NAEP scores in fourth grade reading, Black students

NAEP scores in fourth grade reading, White students

In 2003, economically disadvantaged and Black students in Florida had lower NAEP fourth grade reading scores than their peers in Ohio. By 2022, both student group performed for than 15 points higher than similar students in Ohio. It’s important to note that 10 points is generally seen as a grade level. Mississippi’s success is even more dramatic. They started reforming policies in 2013—a year after Ohio—and their progress has been nothing short of remarkable. As you can see from the NAEP data above, white, Black, and economically disadvantaged students in the Magnolia State closed a sizable gap and now outperform their peers in Ohio.

Ohio students simply aren’t keeping pace in reading with students from Mississippi and Florida. If this was college football, we’d be firing people. But, it’s not. It’s more important.

Ten years ago, Ohio lawmakers decided it would be better to intervene early than have students suffer the consequences later in life. The logic made sense then, and we believe that it’s still true today. Of course, retention—like any policy—isn’t a silver bullet. It must be paired with effective supports, and students need to continue receiving solid instruction in middle and high school. What the policy does, however, is slow the promotional train and give struggling readers more attention and opportunity to catch up.

As data from Florida and Mississippi suggest, it can be done. Their teachers and students aren’t somehow better than ours. What they have had is unflinching state leadership. Ohio students deserve that same commitment. Now is the time to help all students learn to read—not the time to back down.

Thank you for the opportunity to offer public comment, and I look forward to any questions that you may have.