NOTE: On May 24, 2022, the Ohio House of Representatives’ Primary and Secondary Education Committee heard testimony on a bill to eliminate a key aspect of state’s Third Grade Reading Guarantee. Fordham’s vice president for Ohio policy provided testimony against this effort. These are his written remarks.

Reading is absolutely essential for functioning in today’s society. Job applications, financial documents, and instruction manuals all require basic literacy. And all of our lives are greatly enriched when we can effortlessly read novels, magazines, and the daily papers. Unfortunately, even today, roughly 43 million American adults—about one in five—have poor reading skills. Of those, 16 million are functionally illiterate.

Giving children foundational reading skills, so they can be strong, lifelong readers, is job number one for elementary schools. Understanding this, Ohio passed the Third Grade Reading Guarantee in 2012. The law’s aim is to ensure that all children read fluently by the end of third grade—often considered the point when students transition from “learning to read” to “reading to learn.”

The Guarantee takes a multi-faceted approach. It calls for annual diagnostic testing in grades K-3 to screen for reading deficiencies and requires reading improvement plans and parental notification for any child struggling to read. Importantly, it also requires schools to hold back third graders who do not meet state reading standards and to provide them with additional time and supports.

I urge the committee to reconsider the elimination of the guarantee’s retention requirement as proposed in HB 497.

The goal of retention is to slow the grade-promotion process and give struggling readers more time and supports. When students are rushed through without the knowledge and skills needed for the next step, they pay the price later in life. As they become older, many of them will decide that school is not worth the frustration and make the decision to drop out.

An influential national study from the Annie E. Casey Foundation found that third graders who did not read proficiently were four times more likely to drop out of high school. A longitudinal analysis using Ohio data on third graders found strikingly similar results. The consequences of dropping out are well-documented: higher rates of unemployment, lower lifetime wages, and an increased likelihood of being involved in the criminal justice system.

Seeing data such as these, almost everyone agrees today that early interventions are critical to getting children on-track before it’s too late.

Some believe that schools will retain children without a state requirement. Anything’s possible, but data prior to the Reading Guarantee makes clear that retention was exceedingly rare in Ohio. From 2000 to 2010, schools retained less than 1.5 percent of third graders. Retention has become more common under the guarantee, as about 5 percent of third graders were held back in 2018-19. As a result, more students today are getting the extra help they need.

Make no mistake, if HB 497 passes, Ohio will in all likelihood revert to “social promotion.” Students will be moved to the next grade even if they cannot read proficiently and are unprepared for the more difficult material that comes next. There will be relief in the short-run but the price in the long term will be significant.

Data and research

Shifting gears, I’d like to briefly address two claims that have come up in committee hearings related to data and research.

First, some have claimed, based on research studies, that holding back students can have adverse impacts. There is some debate in academic circles about how to assess the impacts of retention. Doing a gold-standard “experiment” with a proper control group is not possible in this situation, so scholars rely on statistical methods that help make apples-to-apples comparisons between similar children. But unless researchers use very careful methods, the results don’t give us much insight.

Arguably, the best available evidence on third-grade retention—as opposed to retention generally—comes from Florida, which has a similar policy to Ohio’s reading guarantee. That analysis, which compared extremely similar students on both sides of the state’s retention threshold, found increased achievement for retained third graders on math and reading exams in the years after being held back. It also found that retained third graders were less likely to need remedial high school coursework and posted higher GPAs. The analysis found no effect, either positively or negatively, on graduation.

If you’d like to review this research for yourself, an essay on the findings by Harvard University’s Martin West, who led the Florida study, was published by the Brookings Institution in 2012. The longer, academic report was published by the National Bureau of Economic Research and in the Journal of Public Economics in 2017.

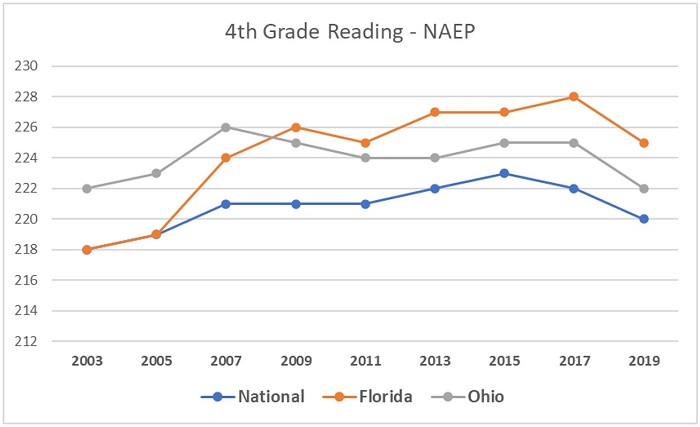

The second claim, particular to Ohio, is that the reading guarantee isn’t producing the improvements we’d like to see. The basis is a paper from The Ohio State University’s Crane Center that notes flat 4th grade reading scores on the National Assessment of Educational Progress from 2013-17. NAEP does offer a useful high-level overview of achievement, but raw trend data are not causal evidence about the impact of the third grade reading guarantee—or any other particular program or policy. The patterns could be related to any number of factors that affect student performance, whether economic conditions, demographic shifts, school funding levels, and much more. Without any statistical controls, it’s impossible to isolate the effect of the reading guarantee.

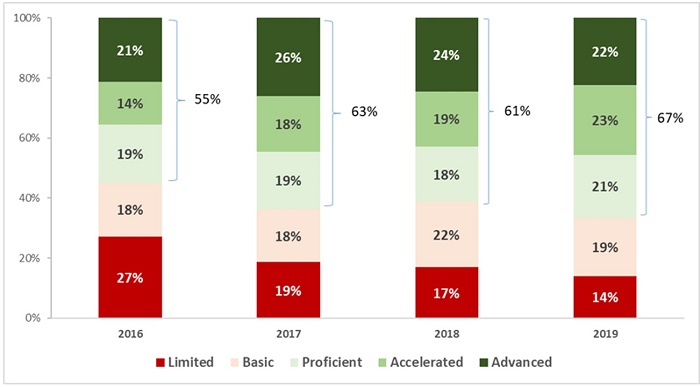

Of course, NAEP isn’t the only yardstick. It’s also worth considering what state testing data show. The chart below shows third grade ELA scores in Ohio. We see an uptick in proficiency rates—from 55 percent in 2015-16 to 67 percent in 2018-19. Also noteworthy, given the guarantee’s focus on struggling readers, is the substantial decline in students scoring at the lowest achievement level. Twenty-seven percent of Ohio third graders performed at the limited level in 2015-16, while roughly half that percentage did so in 2018-19.

Ohio’s third grade ELA scores, 2015-16 to 2018-19

Florida began in 2003 well below Ohio on the NAEP fourth grade reading assessment. By 2019, the Sunshine State was five points—generally seen as half a grade level—above Ohio. Not shown on this chart, the improvements were driven by increased achievement by low-income and Black students.

Much like NAEP trends, this shouldn’t be construed as causal evidence. But the improvements on third grade state exams should be weighed heavily in any analysis on whether the guarantee is improving literacy across Ohio.

Right now, no rigorous evaluation of Ohio’s Third Grade Reading Guarantee and the retention requirement has been conducted; however, the structure of Ohio’s law and the strong data system in place lends itself to a high quality research design. We encourage this committee to request that the Ohio Department of Education conduct a study on this issue before taking action on ending the retention requirement.

The best evidence we have on the impact this policy could have long term is from states like Florida that have rigorously implemented early literacy policies. Again, it’s always hard to say NAEP is causal, but the chart below is certainly impressive.

Note: Florida enacted its reading guarantee in 2002; Ohio enacted its guarantee in 2012. NAEP is given every two years in grades 4 and 8, math and reading, but the 2021 cycle was delayed due to Covid.

* * *

Ten years ago, Ohio lawmakers decided it would be better to intervene early than have students suffer the consequences later in life. The logic made sense then, and we believe that it’s still true today. Of course, retention—like any policy—isn’t a silver bullet. It must be paired with effective supports, and students need to continue receiving solid instruction in middle and high school. What the policy does, however, is slow the promotional train and give struggling readers more attention and opportunity to catch up.

Thank you for the opportunity to offer testimony, and I look forward to any questions that you may have.