NOTE: On Tuesday, February 23, 2021, members of the House Primary and Secondary Education Committee heard testimony on House Bill 67 which would seek to waive testing in Ohio’s schools for the 2020–21 school year. Chad L. Aldis, Fordham’s Vice President for Ohio Policy, gave opponent testimony before the committee. These are his written remarks.

Thank you for giving me the opportunity today to provide opponent testimony for House Bill 67.

My name is Chad Aldis, and I am the Vice President for Ohio Policy and Advocacy at the Thomas B. Fordham Institute. The Fordham Institute is an education-focused nonprofit that conducts research, analysis, and policy advocacy with offices in Columbus, Dayton, and Washington, D.C.

The last year has been incredibly challenging, as we’ve learned to live with Covid-19 and its many impacts. As we’re all well aware, education hasn’t been spared. Last March, students and teachers across the state were thrust into remote learning. Although a significant number of schools have reopened for in-person learning, the extended use of remote and hybrid models has greatly reduced the number of student-teacher interactions.

Recognizing these disruptions, the legislature passed House Bill 409 last December. HB 409 smartly waived state ratings and report cards for the 2020-21 school year and suspends consequences tied to them. This was absolutely the right thing to do and had our full support.

That being said, we believe going a step further and cancelling this year’s assessments would be the wrong decision for Ohio students. Here are four key reasons:

- The shift to distance learning makes it more important than ever to gauge where students are academically. Nationally, experts have suggested that students—especially those already facing the biggest hurdles—may have fallen so far behind that they’ve lost anywhere from 7 to 12 months of learning. A recent study by two Ohio State University professors found that fall 2020 third-grade reading scores fell significantly compared to the year prior. These are useful glimpses that give us more insight into student learning over the past year. However, figuring out exactly which students were most impacted by school closures would allow the state and local schools to effectively target resources, including billions in federal relief aid, to the areas where the biggest learning losses occurred. This is one of the reasons why civil and disability rights organizations have been actively lobbying the Biden administration not to waive state assessments this spring.

- Policy makers need to know how children have been impacted academically, but that information is even more critical for families. Parents recognize the urgency and importance of school and are deeply invested in making sure their children get the most out of it. If a student hasn’t learned what they are supposed to learn, it is often their parents or guardians who are in the best position to advocate for additional support. They can’t do this without accurate and detailed information about their student’s progress, though. And while feedback from teachers and schools matters, state assessments are crucial because they objectively measure student performance against state learning standards and can identify potential learning gaps that could cause problems down the road. Getting this information into the hands of parents is crucial, as it can help them decide if they need to seek additional assistance for their child.

- This past year has been tough, and we’re all hoping we’ll never have to repeat it. But it’s imperative that as we move on, we learn lessons from this difficult experience so that schools are better prepared to educate students in more flexible learning environments going forward. Because state test results are comparable across communities, state testing can help us identify which communities had the most success during this trying time. There’s much we can learn from this experience, but having high quality data to examine what worked is essential.

- Eventually, this pandemic will pass. When it does, it’ll be important to have baseline data to gauge how schools perform in the years after 2020-21. This is critical for report card elements like student growth and achievement gaps—the fairest measures to high poverty schools—as they require multiple years of data. By administering spring assessments in 2021, we’ll be able to establish a new normal and begin to track the progress of academic recovery moving forward.

While I believe the case for testing this school year is strong, there have been some concerns raised. Here are a few of the most common:

- First, some have said that it’ll take away too much instructional time. On this count, we have to bear in mind the facts about time on state assessment. In a recent report by the Ohio Auditor of State, his team reported that students spend less than 1 percent of their year taking state tests. Depending on grade level, Ohio students spend between five and ten hours per year taking state exams. It’s true, of course, that prepping for tests takes more time than that. But since test prep doesn’t typically translate to meaningful learning increases for students, schools should take advantage of the pause on accountability to get rid of test prep all together.

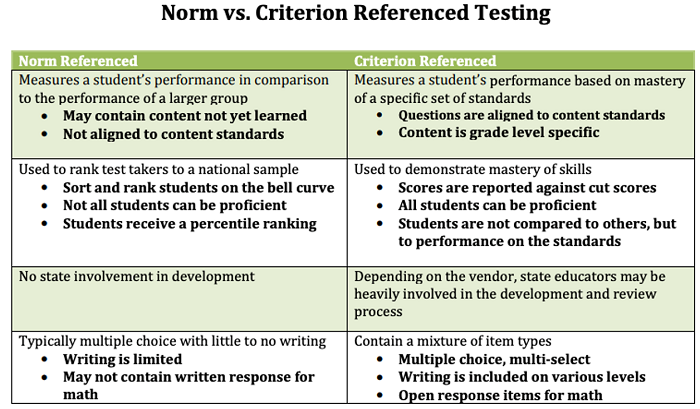

- Second, many have argued that diagnostic tests give us sufficient information about where students stand. These tests offer a rapid assessment of student learning that allows teachers to tailor instruction and make course corrections during a school year. But they also have limitations. Most glaringly, there’s no public information on performance. They are also almost always norm-referenced tests rather than criterion-based tests. Here’s a helpful chart from the University of Arkansas showing the difference:

Criterion-based tests are linked to the state’s learning standards. They don’t just give a student’s relative rank compared to students across the country. They measure whether a student learned what students in their grade are supposed to have learned. That’s what we need right now, because that’s the information that matters most—not how students compare to other students, but how much students have (or haven’t) learned.

- Third, some suggest that we already know there was learning loss, so testing is unnecessary. On average, it’s almost surely true that the typical student has suffered losses due to the disruptions. The averages, however, mask significant variation in the learning experiences—and outcomes—of students. Consider the earlier referenced study of data from Ohio’s fall third grade ELA assessments. While the average third grade test score fell significantly, we also see that eighty-four districts and charter schools posted higher proficiency rates in fall 2020 versus the previous fall. Twenty-eight of these schools had economically disadvantaged rates of more than 50 percent. That means that, contrary to the conventional wisdom that low-income students universally lost ground, some high-poverty schools actually prevented significant loss for their students. Without an objective and comparable state test, though, we won’t know which schools did well or which student subgroups need the most help.

***

No one truly knows how districts or schools—let alone individual students—have fared over the past year. The danger of making policies or decisions based on assumptions about who is doing well or poorly is that students won’t be served well. Some may be consigned to remediation when they are actually ready to zoom ahead. Conversely, children struggling academically may get overlooked, allowing them to fall through the cracks. Parents may fail to get the information they need to take action on behalf of their child. To ensure that decisions aren’t being made based on false assumptions or incomplete information, we need data from assessments about where each student stands against Ohio’s academic standards.

Thank you for the opportunity to provide testimony.