NOTE: Today, the Ohio Senate’s Primary and Secondary Education Committee heard invited testimony on HB 110, the state budget bill. Fordham’s Vice President for Ohio Policy was invited to testify on topics related to school funding and interdistrict open enrollment. These are his written remarks.

My name is Chad Aldis, and I am the Vice President for Ohio Policy at the Thomas B. Fordham Institute. The Fordham Institute is an education-focused nonprofit that conducts research, analysis, and policy advocacy with offices in Columbus, Dayton, and Washington, D.C. Our Dayton office, through the affiliated Thomas B. Fordham Foundation, is also a charter school sponsor.

Last week, I touched on a host of school funding and education policy issues in House Bill 110. In that testimony, I mentioned some of the strengths of the House school funding plan, including its elimination of funding caps, the increased focus on providing adequate resources for low-income students, and the shift to direct fund choice programs. The House should be commended for their work in those areas. In today’s testimony, however, I’ll limit my comments to three specific areas in school funding that merit further discussion: guarantees, interdistrict open enrollment, and outyear funding.

Guarantees

Ohio has long debated “guarantees,” subsidies that provide districts with excess dollars outside of the state’s funding formula. These funds are typically used to shield districts from losses when the formula calculations prescribe lower amounts due to declining enrollments or increasing wealth. In FY 2019—the last year in which funds were allotted via formula—335 of Ohio’s 609 school districts received a total of $257 million in guarantee funding. The guarantee, it’s worth noting, isn’t directly tied to poverty: A number of higher-wealth districts benefitted from the guarantee in 2019.

Guarantees undermine the state’s funding formula whose aim is to allocate dollars efficiently to districts that most need the aid. Districts on the guarantee receive funds above and beyond the formula prescription, while others receive the formula amount—sometimes even less due to the cap. Because guarantees are usually related to enrollment declines, they effectively fund a certain number of “phantom students” who no longer attend a district.

Among the main ideas of HB 110 is to get all districts on the same formula. That’s exactly the right goal. But while the legislation removes caps, it does not adequately address guarantees. Let me raise three specific issues:

- Permanent guarantee. In a new section of law (3317.019), House Bill 110 creates a permanent guarantee that ensures no district loses state funding on a per-pupil basis starting in FY 2024. While no estimates have been released on how many districts this may apply to, or what the cost to the state may be, it’s concerning to see the continued reliance on guarantees to fund some districts.

- Supplemental targeted assistance. In another new section of law (3317.0218), House Bill 110 would send excess money outside of the formula to districts where significant numbers of resident students have enrolled in choice programs. Certain low-wealth districts where more than 12 percent of students attended public charter schools or used private-school vouchers in 2019 would receive an annual bump in state funding, anywhere from $75 to $750 per pupil. This policy, which is akin to funding phantom students, is estimated to cost the state $56 million per year. That may not sound like a large amount of money, but it’s happening at the same time the budget is being phased in and districts are receiving less—sometimes much less—than the formula says that they should.

- Staffing minimums. Though not a guarantee in a traditional sense, HB 110 includes something like it in its base cost model. School districts—though not charter schools—are guaranteed a minimum number of special teachers, and SEL and administrative staff, even when the plan’s specified staff-to-enrollment ratios would have resulted in lower staffing support. Such minimums boost the base costs of low-enrollment districts, thus creating a small-district subsidy that is funded like a de facto guarantee within the base cost formula.

Interdistrict open enrollment

Open enrollment is an increasingly popular public school choice program, especially among families living in Ohio’s rural areas and small towns. More than 80,000 students today use interdistrict open enrollment to attend public schools in neighboring districts. Research commissioned by Fordham has shown that students who consistently open enroll benefit academically, especially students of color.

Under current policy, the funding of open enrollees is fairly straightforward. The state subtracts the “base amount”—currently a fixed sum of $6,020 per pupil—from an open enrollee’s home district and then adds that amount to the district she actually attends. Apart from some extra state funds for open enrollees with IEPs or in career-technical education, no other state or local funds move when students transfer districts.

In a wider effort to “direct fund” students based on the districts they actually attend, House Bill 110 eliminates this funding transfer system for open enrollment. Open enrollees are included in the “enrolled ADM” of the district they attend and thus receive the same level of state funding as resident pupils of that district. While this seems to make sense at face value, the approach results in significantly lower funding for most open enrollees relative to current policy, creating disincentives especially for mid- to high-wealth districts to accept open enrollees.

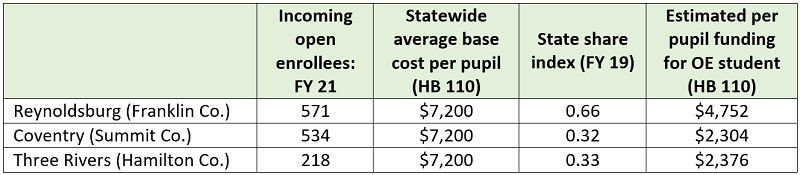

The table below illustrates how applying the state share reduces funding for open enrollment, using three districts that have significant numbers of open enrollees this year. Note, we use the district’s state share index from FY 2019 and the average statewide base cost under HB 110, because those data were not available in the funding simulations. What we see is that open enrollment funding is significantly reduced relative to the current $6,020 per pupil once the state share is applied. Will districts like Coventry and Three Rivers continue to offer open enrollment when per-pupil funding is cut by more than half? Will wealthy districts that currently refuse to participate open their doors when the state funding is so low? Remember that under current policy districts voluntarily participate in the program—it’s not required—so the funding amounts are crucial to opening these opportunities to students.

Illustration of open enrollment funding in HB 110

Some have suggested that the new formula when fully phased in won’t create a disincentive in regards to open enrollment and will adjust to produce a funding amount similar to what open enrollees currently receive. If true, that’s fantastic. It’s not in the legislative analysis, and it’s not explicitly in HB 110. This is too important to leave to chance. Please add language to ensure that open enrollees continue to receive adequate funding.

Outyear funding

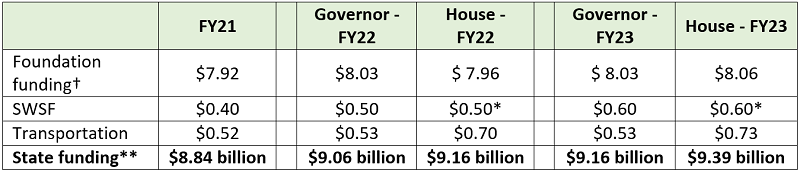

As has been widely reported, the overall price tag of the House funding overhaul is estimated to be an additional $2 billion per year. Yet, as the table below indicates, HB 110 calls for generally modest increases in education spending in the next biennium. Relative to the Governor’s plan, the House raises state education funding by roughly $100 million in FY 2022 and $230 million in FY 2023. Most of those dollars go into transportation rather than into the classroom.

An overview of state education funding, current and proposed (in billions)

*In the House plan, the Student Wellness and Success Funds remain a standalone line item, but are used to fund an increase in the economically-disadvantaged component of the funding formula and the SEL portion of the base cost model. **This excludes federal and local dollars, various smaller state expenditures (e.g., educator licensing and assessments), and money for K–12 education not funded via ODE budget (e.g., school construction dollars and property tax reimbursements). † This includes the additional $115 million that was included in the omnibus amendment to the House budget.

The six-year phase-in of the funding increases called for by HB 110 explains the relatively small increases. While this gradual approach may have been necessary, it continues to raise questions about how the rest of the funding model will be paid for. Will future lawmakers need to raid other parts of the state budget to pay for increases, as HB 110 does with the Student Wellness money? Or are they leaving the heavy lifting—possibly raising taxes—to future lawmakers? And what happens when there are calls to re-compute the base costs using up-to-date salaries and benefits, instead of 2018 data? We’ve already heard this committee discuss the need for an additional $454 million to fund based on FY 2020 salary levels. While it might be fine to use three-year-old salary data now, won’t using FY 2018 data be a problem in FY 2026? This alone gives considerable uncertainty about how this funding model can be sustained over the long run.

***

Funding the education of 1.8 million Ohio students is an incredible responsibility, and I commend legislators in both the House and Senate for their diligent work in this area. Creating a fair, sustainable—and student-centered—funding model remains one of the most challenging areas in education policy. For the past two decades, Ohio has made significant progress in funding education, and with additional, smart reforms, we can continue to create a system that is fair, equitable, and built to last.

Thank you for inviting me to share my thoughts and I welcome your questions.