NOTE: Today, the Ohio House's Finance Subcommittee on Primary and Secondary Education Committee heard testimony on House Bill 33, legislation establishing the state’s budget for fiscal years 2024 and 2025. What follows is the written proponent testimony submitted by Fordham’s Vice President for Ohio Policy.

Right now is a pivotal time for K–12 education in Ohio. The pandemic has knocked students off-track and widened longstanding achievement gaps across the state. The most recent data indicates that one in every four students scored at “limited”—the state’s lowest achievement level—on their state exams in spring 2022. The numbers rise to 37 percent for economically disadvantaged students and 56 percent for students with disabilities. While graduation rates remain high, too many students exit high school without the real preparation they need for college and career. Less than 10 percent of students earn meaningful industry credentials before graduation, and only one in five meet college-ready benchmarks on their ACT exams.

With these challenges in mind, we are excited about Governor DeWine’s strong focus on K–12 education in his budget. As the governor noted in his state of the state, there is a moral imperative to ensure that every Ohio student receives an education that unlocks their full potential. We are equally pleased by the specific policies he put forward that would move Ohio towards achieving this goal. In my comments, I’ll highlight several of the governor’s proposals that Fordham strongly supports, as well as offer some ideas that would further strengthen this legislation.

- Early literacy: We strongly commend the governor’s efforts to improve literacy through an emphasis on effective instructional practices and curricula. The research is clear: Instruction that is anchored in phonics, background knowledge, and vocabulary is absolutely critical for fluent reading.[1] We support requirements that schools adopt high-quality curricula and instructional materials aligned to the science of reading, as well as budget allocations that would ensure schools have the resources needed to rigorously implement effective practices.

- Career-and-technical education: We applaud the governor for his strong investments in high-quality career-technical education (CTE), a pathway that can open doors to rewarding careers for many Ohio students. We’re especially pleased to see continuing support for an incentive program that provides schools with an extra $1,250 when students earn an in-demand industry credential, as well as an extra $1,000 per pupil when students complete 250 hours in a work-based learning program.

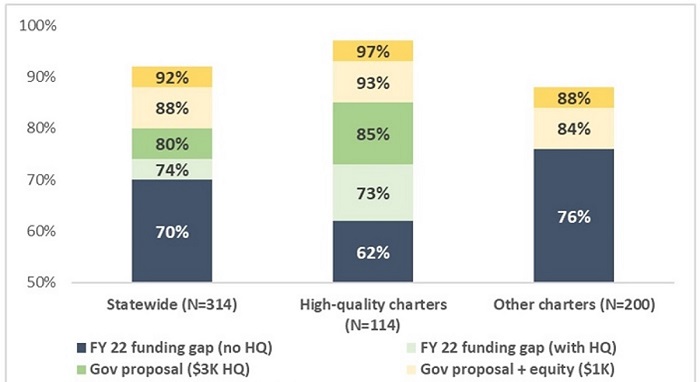

- High quality community school funding: Turning to matters of school choice, we strongly support the increase in the high-quality community school funding proposed by the governor. For far too long, community schools (a.k.a. charter schools) have been asked to serve students with less overall funding than local districts. The high-quality fund helps bridge that gap for about a third of Ohio’s community schools. The governor’s proposal would increase the amounts qualifying schools receive from $1,750 per economically disadvantaged pupil to $3,000 (and from $1,000 to $2,250 per non-disadvantaged student). This would boost the funding received by high-quality community schools to 85 percent of their local district funding—up from 73 percent currently. The extra aid will help quality schools retain great teachers, provide more supports and enrichment for their students, and allow schools to reach a larger number of students.

- Community school facilities. Ohio’s community schools receive little support for facilities. They are not eligible for the state’s main school construction grant program and cannot access local tax sources to pay for facilities. To help cover these costs, Ohio currently provides community schools with a facility allowance of $500 per pupil. The governor proposes a much-needed increase to $1,000 per pupil, an amount that would track closer to districts’ spending on capital outlay.

- EdChoice scholarships. We applaud the governor’s proposal to empower more Ohio families with private school choice through expanded eligibility for income-based scholarships. Even with the recent expansions to EdChoice, many middle-income families still remain ineligible for the financial assistance. A family where mom works as a police officer and dad as a teacher is likely over the current income threshold of $75,000 for a family of four. Raising the income threshold to 400 percent of federal poverty would ensure that working class families are not squeezed out and have access to the program. Of note, we also support ongoing efforts to go further and make scholarship eligibility universal and open to all Ohio families.

Going beyond the governor’s proposals, we wish to offer two additional ideas that would also strengthen choice in Ohio.

- Make the high-quality community school fund part of the funding formula. As in prior years, the budget bill funds this program via line-item appropriation with temporary language. We encourage the legislature to move this program into the community school funding formula in Revised Code. This would put these funds on an equal footing with other formula components and would help avoid reductions to the per-pupil funding amounts that have occurred in recent years due to the fixed appropriation.

- Create a community and STEM school equity supplement. As noted above, Ohio has long shortchanged public community schools, historically funding them at about 70 cents on the dollar compared to local districts. But other states, such as Massachusetts and Texas, fund charters more equitably at roughly 85-95 percent of district funding.[2] While the high-quality supplement helps bridge the gap, it still leaves sizable differences in funding for community school students—most of whom are low-income or students of color. To fund their education fairly, we recommend the creation of an equity supplement that would provide all brick-and-mortar community schools and the state’s seven independent STEM schools with an extra $1,000 to $1,500 per pupil. At the higher amount, this would bring the average charters’ funding—when combined the quality funding initiative—to 92 percent of districts. The figure below shows how an equity supplement, paired with the high-quality dollars, would help to bring community school funding to near parity with districts.

Figure 1: Impact of a community school equity supplement[3]

School funding formula

Turning last to the school funding formula. As we all know, the formula is an incredibly complex mechanism. That was true with the formulas used by Ohio in the past, and it’s still the case with the new model implemented by the last General Assembly.

We strongly believe that Ohio needs a well-designed and properly functioning formula, one that drives dollars to the neediest schools—those with the least capacity to raise funds locally—including via the state-required 2 percent, or 20 mill, property tax—along with schools that serve more students who have special-needs or are economically-disadvantaged. The dollars provided by the state are critical to ensuring that all students have the resources needed to achieve at high levels.

It’s no secret that Ohio has struggled to create a workable, sustainable formula. While the new formula was supposed to address the problems that plagued prior iterations, we believe the new system, which Governor DeWine has proposed to continue phasing-in, also has challenges of its own. There isn’t time to cover all the issues, but we wish to point out just a few areas of concern.

Base cost model: One of the new formula’s most distinctive elements—and the source of its well-known expense—is a base-cost model that helps to determine the core state funding of each district. The model relies on various inputs—employee salaries, staffing ratios, and other data points—in an effort to calculate the cost it takes to educate a typical student. This model, which is more art than science, yields a somewhat different base amount for each district.

One challenge with the model is that it currently uses FY 2018 salary data. Even with those old numbers, the formula still cost enough that the legislature opted to phase-in additional state dollars, which is effectively a statewide cap on funding. What happens if the salary data are updated to more current numbers? How much will that add to the formula’s price tag? What impact have the federal Covid-relief dollars had on salaries? If they increased as a result, will the state be responsible for increased outlays because of inflationary federal spending?

Another issue is the base cost model’s staffing minimums that “guarantee” low-enrollment districts—though not charter schools—funding for a certain number of staffing positions. These minimums deviate from the formula calculations, in effect providing about one-sixth of Ohio districts with a hidden special subsidy. In a few cases, these minimums cause their base amounts to soar over $10,000 per pupil (versus a statewide average of about $7,300). This guarantee also discourages efficiencies, such as shared services between smaller districts or using educational service centers for extra support.

We suggest shifting to a flat base amount for all districts and charters that is simpler, more predictable, and doesn’t build-in guarantees or inflationary adjustments that are not driven by the state legislature. This would acknowledge the work of the prior General Assembly and many workgroups involved in the Cupp-Patterson effort to figure out a base cost. It would also open the door for full funding of the model right now. Importantly, future lawmakers could easily adjust the base for inflation, rather than face the uncertainty about the fiscal impact of fully updating all the many “inputs” inside the base-cost model.

Disadvantaged pupil impact aid (DPIA): Ohio has long included a funding component that directs additional dollars to districts and charter schools that serve more economically disadvantaged students. The rationale is sound—low-income students typically require more supports—but the current implementation is faulty due to Ohio’s longstanding method for identifying such students, which is through free and reduced priced lunch eligibility (FRPL). Starting in 2010, certain districts and schools are now allowed under federal law to offer subsidized meals to all students, regardless of their family incomes. For the purpose of providing lunches, that’s just fine. But, as a result, a sizeable number of districts now overstate the number of economically disadvantaged students. Last year, 72 districts reported that 95 to 100 percent of their students were economically disadvantaged. Ten years ago, just one district reported rates that high. This overidentification causes an inefficient allocation of DPIA funding and reduces the dollars available for schools that actually serve more low-income students.

To address this issue, Ohio should replace FRPL eligibility as the marker for low-income status with “direct certification” counts. Under this method, low-income students are identified through their families’ participation in means-tested programs, such as SNAP, TANF, or Medicaid. Using these counts would yield more accurate data on the number of low-income students; in turn, the state would better target DPIA to the schools that need the extra dollars most. This could also free up dollars to allow an increase in DPIA’s base per-pupil amount, which would further enhance the funding directed to the highest-poverty schools in Ohio.

***

In conclusion, Ohio has a lot of work ahead to ensure that all students thrive academically and reach their full potential. The need for quality educational opportunities is even more urgent in the wake of the pandemic. We thank Governor DeWine for his focus on education and an excellent budget proposal that puts Ohio parents and students first. As the bill moves forward, we ask lawmakers to embrace his proposals and consider ideas that would further strengthen education for Ohio’s 1.8 million students.

Thank you for the opportunity to speak with you today.

[1] For an accessible overview of the science of reading, see Emily Hanford’s reporting on the topic: https://features.apmreports.org/reading/. For a more technical discussion, see Anne Castles, et. al., “Ending the Reading Wars,” https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1529100618772271.

[2] Corey A. DeAngelis, et. al., Charter School Funding: Inequity Surges in the Cities: https://scholarworks.uark.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1080&context=scdp.

[3] More details about the calculations are at: https://fordhaminstitute.org/ohio/commentary/ohio-narrowing-charter-funding-gap-it-still-needs-do-more.