Senators and Representatives: It’s an honor to be with you today. My name is Mike Petrilli; I’m the executive vice president of the Thomas B. Fordham Institute, a right-of-center education-policy think tank in Washington, D.C., that also does on-the-ground work in the great state of Ohio. I was honored to serve in the George W. Bush Administration; my boss, Chester Finn, served in the Reagan Administration. Perhaps most importantly, I was raised in the Midwest, in St. Louis, Missouri. It’s great to be back in the heartland. (Go Cardinals!)

As a strong conservative and a strong supporter of the Common Core, I’m here to urge you to stay the course with these standards and with the Smarter Balanced assessments.

Still, unlike some other Common Core supporters, I’m glad that you are holding this hearing and debating the issue of whether Wisconsin should stick with the Common Core. These standards were developed by the states, and to be successful, they need to be owned by the states. Our educators are all too familiar with the “flavor of the month”—reforms that come and go. They are wondering if they should wait this one out too. By having this open debate on the Common Core, you can settle the issue once and for all—and either change course or move full speed ahead.

It’s also true that when states, including Wisconsin, adopted these standards three years ago, there wasn’t nearly enough engagement of parents, teachers, or policymakers. I believe a lot of the resistance we’re now seeing to the Common Core is because many people are just learning about them for the first time, and want their voices and concerns heard. So hearings like this one are critically important.

Today I want to address some of the common concerns we hear about the Common Core standards. Before that, though, I want to remind us what this effort to raise standards is all about.

At Fordham, we believe that smart education reform combines two big strategies: Expanding parental choice, and setting and implementing rigorous standards. Wisconsin can be proud of its record on the first—school choice. Home to the nation’s first voucher program, recently expanded statewide, as well as an active charter school sector, the Badger State should be commended for its efforts to make options available to all parents that in many states are still reserved for just the well to do.

Unfortunately, the same cannot be said about Wisconsin’s work on standards based reform. I don’t think it’s unfair to argue that Wisconsin has one of the worst records in the country when it comes to setting strong standards and rigorous tests, and your results show it.

Let’s start with the standards Wisconsin had in place before the Common Core. In 2010, we reviewed the English and math standards of the fifty states, and compared them to the Common Core. We’ve been doing similar reviews of state standards for fifteen years. And the results? The Common Core standards were good enough to earn an A-minus in math and a B-plus in English, significantly better than the grades of three-quarters of the states, and on par with the rest.

And Wisconsin? Your English standards received a D from our expert reviewers, and your math standards received an F. They were among the worst standards in the country.

What was so bad about them? Let me quote from our review, first for English:

While Wisconsin’s standards include some clear and rigorous content, their failure to delineate grade-specific expectations leads to the omission of much critical K-12 content, beginning with early reading. Only three standards touch on any content related to phonics, phonemic, or phonological awareness….Vocabulary standards are inadequate and omit such important content as synonyms, antonyms, compound and multiple meaning words, and denotation. With the exception of [one overly-broad standard], the state fails to include any standards that reflect the importance of reading American literature…

Nor does Wisconsin provide explicit guidance regarding the amount, quality, or complexity of texts that students should be reading each year, much less any actual titles. The state fails to include expectations that clarify the characteristics and quality of writing that students should produce in each grade. In addition, standards addressing English language conventions are vaguely worded and omit some essential grade-appropriate content.

And now for math:

The standards are missing much essential content. Single-digit number facts are to be recalled, but not quickly or instantly. Whole-number arithmetic has basically no development and is missing both fluency and standard methods and procedures.

[The standards equate] calculators with pencil and paper methods. In the continued standards on arithmetic in eighth grade, common denominators are not mentioned, and the standard algorithms are undermined with “computational procedures for rational numbers” such as: [C]reating, using, and explaining algorithms (grade 8). This gives alternative algorithms the status that standard methods should have.

Now, perhaps Wisconsin could overcome the weaknesses in its standards by producing a rigorous test. But that has not been the case. In fact, Wisconsin’s reading and math tests are among the weakest in the country. In another Fordham Institute report, The Proficiency Illusion, we found that Wisconsin’s proficiency cut scores—the level of reading and math skills that it took to get a passing score—were significantly below the average for all states studied. That’s saying a lot, as cut scores nationwide are notoriously low.

To be specific, we found that Wisconsin set its third grade reading proficiency cut score at the 14th percentile nationally. That means that you could be reading worse than 86 percent of the students in the nation, and the state of Wisconsin would tell you and your family and your teachers that you were doing fine.

Is it any wonder, then, that many young people in Wisconsin arrive on colleges like this one unprepared to do college level work? And are then dumped into remedial education, meaning that their parents, or taxpayers, have to pay twice for a high school education? According to a recent study, Wisconsin taxpayers could have saved some $66 million in 2007-08 on such remediation.

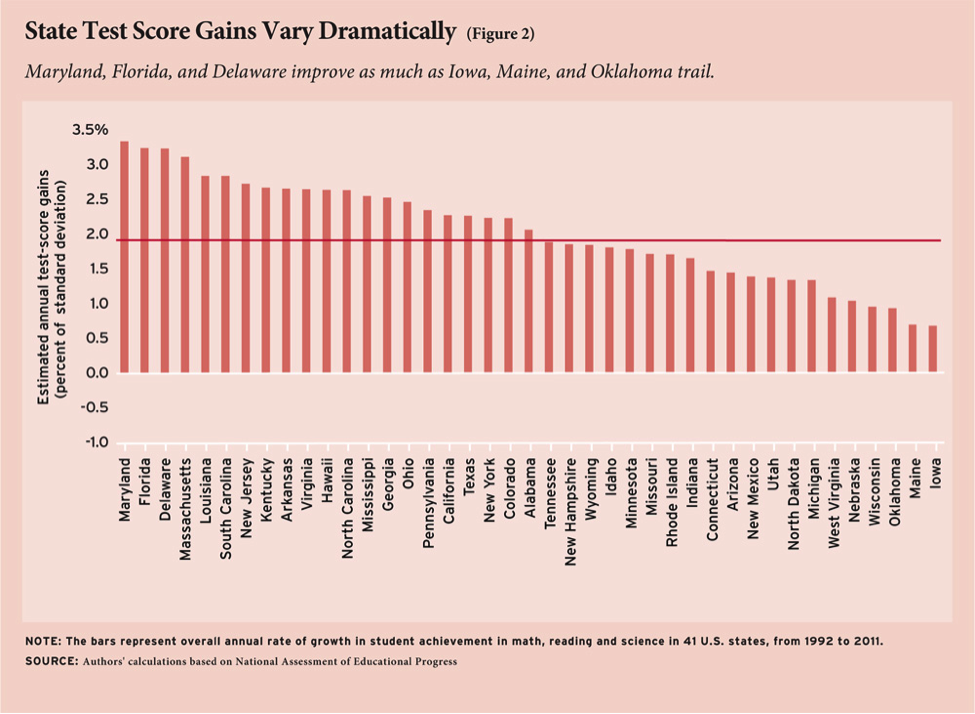

And what was the result of years of vague, low standards and ridiculously easy tests? While other states were making big gains in reading and math, Wisconsin was standing still.

Only three states in the country have made less progress than Wisconsin in boosting achievement in math, reading, and science since the early 1990s.

So let me ask you: Is this good enough for Wisconsin? I don’t think so, and I don’t think you think so. Wisconsin clearly needs a new approach.

Enter the Common Core

In the mid-2000s, the nation’s governors and state superintendents started to acknowledge that their own standards and tests were not rigorous enough to prepare students for what comes next: Either college or a good paying career. So they agreed to collaborate on a new set of standards that would be guided by the best research and evidence, be modeled after the standards of high performing states and nations, and that would ensure that high school graduates would be ready for success in college and career. At the end of the process were the Common Core State Standards.

They aren’t perfect. As I mentioned earlier, they received an A-minus and a B-plus from our reviewers, respectively, for math and English. But they’re pretty darn good. The math standards are incredibly solid on arithmetic, expecting students to know their math facts cold, to memorize their multiplication tables, to use standard algorithms, and not to use calculators until they are older. The English standards ask schools to bring back rigorous content in history, science, art, music, and literature. That’s why E.D. Hirsch, founder of the Core Knowledge program and author of Cultural Literacy, is such a big fan of them. They ensure that students read great works of literature and solid non-fiction sources too, like the nation’s founding documents.

So why is there so much controversy? Let me respond to some of the major critiques:

First, that the standards themselves are flawed.

Second, that the standards are creatures of the federal government.

And third, that the standards open the door to inappropriate intrusions into our children’s privacy.

The quality of the standards

Some critics allege that the Common Core standards inappropriately prioritize nonfiction over literature in language-arts classrooms.

This is based on a misreading—or deliberate manipulation—of a two-paragraph section found on page 5 of the introduction to the Common Core that mentions the NAEP assessment framework, which suggests that teachers across content areas should “follow NAEP’s lead in balancing the reading of literature with the reading of informational texts, including texts in history/social studies, science, and technical subjects.” Following NAEP’s lead would mean that fourth, eighth, and twelfth graders would spend 50, 55, and 70 percent of their time (respectively) reading informational text.

Some critics have led people to believe that these percentages are meant to direct learning exclusively in English classrooms. They are not. In fact, the Common Core immediately clarifies that “the percentages…reflect the sum of student reading, not just reading in English settings. Teachers of senior English classes, for example, are not required to devote 70 percent of reading to informational texts.” Reading in social studies and science class would count too.

Dr. Sandra Stotsky, who the committee heard from at a prior hearing, and others have also charged that the Common Core will push high-quality literature out of the classroom. Balderdash. In fact, the standards devote a disproportionately large amount of attention on demonstrating the quality, complexity, and rigor of the texts students should be reading each year. Appendix A includes a list of “exemplar” texts, the vast majority of which are works written by literary giants like Throeau, Chaucer, Shakespeare, Harper Lee, and Nathaniel Hawthorne. The small number of technical documents included in these lists is dwarfed by the volume of great authors, works of literature, and literary nonfiction that the standards hold up as exemplary.

In fact, just the other day, Politifact declared the allegation that Common Core pushes classic literature out of the curriculum to be “false.”

And what about math? Some critics allege that the Common Core standards promote low-level mathematical skills or that they prioritize mathematical “practices” or “fuzzy math” over critical content. Again, a close reading of the standards reveals the opposite is true.

The Common Core math standards prioritize essential content. In the early grades, this means that arithmetic is heavily weighted, that students are asked to learn to automaticity their basic math facts, and that they are asked to master the standard algorithms. This is content they need to know—cold—in order to be prepared for the upper level math work they will do in high school and beyond. If there is one thing we know with certainty, it’s that math is cumulative. You can only move on to more advanced content when you have fully mastered essential prerequisite knowledge and skills.

Some critics complain that the standards don’t require Algebra in the eighth grade, something that many think is essential to prepare students for advanced math in high school. The reality, however, is that the Kindergarten through seventh grade Common Core standards include all of the prerequisite content students will need to have learned to be prepared for Algebra I in the eighth grade. And that means that it’s the states, districts, and/or schools who decide for themselves course and graduation requirements. In fact, this committee has heard from numerous school and district educators and leaders who have testified both in favor of the Common Core and noted their use of Algebra in the eighth grade.

Some have implied that few mathematicians signed off on the quality of the standards. Again that’s simply not true. The committee that wrote the standards included over a dozen academic mathematicians, including its chairman, a mathematician from Harvard. These are not acolytes of fuzzy math. And the quality of the standards shows it.

What’s more, research by William Schmidt, a leading expert on international mathematics performance and a previous director of the U.S. TIMSS study, has compared the Common Core to the standards of high-performing countries in grades K–8. The agreement was very high between the Common Core math standards and the math standards in place in the highest performing nations. In fact, Schmidt and his colleague found that no state's previous math standards were as close a match to those of high-performing countries as the Common Core.

Perhaps even more critically, Schmidt’s research found that “states whose previous standards were most similar to the Common Core performed better on a national math test in 2009.” That means that, across the nation and the world, students whose learning was driven by standards that closely resembled the Common Core fared better than students who lived in states whose standards looked very different.

The Federalism concern

The second major charge against the Common Core is that they are creatures of the federal government. Here I have more sympathy with the critics. It’s certainly true that President Obama politicized the standards by using federal Race to the Top dollars to coerce their adoption by the states. It got even worse when the president took credit for the common standards every time he had a chance on the campaign trail—and when he did it again in this year’s State of the Union address.

But the history is very clear. These standards started out as a state effort, with support from private entities like the Gates Foundation. It was the governors and state superintendents who came together, voluntarily, to draft higher common standards, because they acknowledged that their own state standards were set too low. There was already momentum behind the standards when the Obama administration intervened.

Thankfully, in my view, Republicans in Congress are working to ensure that not another cent of federal funding, and not a whiff of federal coercion, is allowed going forward when it comes to the Common Core.

The Common Core started out as state standards, and they need to remain state standards. Washington needs to butt out.

Privacy concerns

Finally, some critics of the Common Core have alleged that the standards open the door to invasions of privacy, to data warehouses that will allow the government to snoop on our children and families or even sell sensitive data to for-profit companies.

This is simply not true.

As a parent of young children, I definitely worry about privacy, and recent examples of Big Government and Big Data are unsettling. But there’s nothing, repeat, nothing about the Common Core that requires a particular data collection or an assault on privacy, as even the Cato Institute’s Neal McCluskey, one of Common Core’s sharpest critics, acknowledges.

Wisconsin has strong data privacy laws and practices but could further strengthen them if legislators so chose. However, to be clear, if the Common Core were dispensed with in Wisconsin tomorrow, that would not in any way address these fears about data privacy.

Common Core: A conservative victory

With those rebuttals behind me, let me explain why we at the Fordham Institute are so bullish on the Common Core—why we see them as a strong conservative victory.

- Fiscal responsibility. The Common Core protects taxpayer dollars by setting world-class academic standards for student achievement—and taxpayers and families deserve real results for their money.

- Accountability. Common Core demands accountability, high standards, and testing—not the low expectations and excuses that many politicians and the establishment have permitted.

- School choice. The information that comes from standards-based testing gives parents a common yardstick with which to judge schools and make informed choices. In the end, Common Core is not a national curriculum—the standards were written by governors and local education officials, and they were adopted by each state independently.

- Competitiveness. While the U.S. dithers, other countries are eating our lunch. If we don’t want to cede the twenty-first century to our economic and political rivals—China especially—we need to ensure that many more young Americans emerge from high school truly ready for college and a career that allows them to compete in the global marketplace.

- Innovation. Common Core standards are encouraging a huge amount of investment from states, philanthropic groups, and private firms—which, in turn, is producing Common Core–aligned textbooks, e-books, professional development, online learning, and more. Online learning especially is going to open up a world of new choices for students and families to seek a high-quality, individualized education. It’s as if the whole world is moving to smart phones and tablets while you’re sticking with a rotary.

- Traditional education values. The Common Core standards are worth supporting because they’re educationally solid. As I explained earlier, they are rigorous, they are traditional—one might even say they are “conservative.” They expect students to know their math facts, to read the nation’s founding documents, and to evaluate evidence and come to independent judgments. In all of these ways, they are miles better than what Wisconsin had in place before.

We see the Common Core as a conservative triumph. The standards are solid and traditional. They don’t give in to moral relativism, blame-America-first, or so many other liberal nostrums that have infected our public schools.

Let me finish with a question. If Wisconsin backs away from the Common Core, or the Smarter Balanced assessments, then what? Are you really going to return to your lousy standards and ridiculously easy tests? If not, what process will get you to better standards than the Common Core? Perhaps even more critically, if you don’t use the common assessments, how are you going to develop an alternative, with less than eighteen months to go until these tests are to be given for the first time? An independent study in Indiana found that if that state pulled out of the common assessments, it would have to spend $30 million to replace it with something home grown. Are you prepared to spend that kind of money to placate concerns that are largely based on misinformation and fear?

Wisconsin took a big step forward with the Common Core. Your educators are three years into this effort. Teachers have been retrained. New textbooks purchased. A new assessment is about to be field tested. Higher standards finally have momentum in the Badger State. Don’t slow down—or turn back—now.