First implemented in the 2013–14 school year, Ohio’s third grade reading guarantee has aimed to ensure that all children have the foundational reading skills needed to navigate more challenging material. The early literacy policy has many facets, including fall reading diagnostic assessment in grades K–3, mandatory parental notification and reading improvement plans if a child is deemed off-track, and retention and intensive interventions if a student doesn’t achieve a benchmark score on a third grade exam.

This early warning and intervention system was created in part as a response to research showing a link between children’s early literacy skills and their academic outcomes later in life. The most influential analysis was a 2011 Annie E. Casey Foundation report that found non-proficient readers in third grade were far more likely to drop out of high school than their peers. Subsequent analyses have uncovered similar results. An analysis of Ohio data discovered that non-proficient readers in third grade were three times more likely to not graduate. A recent study of Massachusetts, North Carolina, and Washington State data found that students who struggle to read in third grade take fewer advanced high school courses and have lower graduation rates.

Despite the well-documented importance of early literacy, the third grade reading guarantee has endured much criticism. The attacks have largely centered on the mandatory retention policy that critics have decried as punitive. Of course, that’s hardly the intention. It’s there to ensure that children struggling to read aren’t being robotically passed to the next grade, but actually receive the extra help they need. The policy is also supported by rigorous studies from Florida and Chicago showing that retention in early grades can give low-achieving students an academic boost.

Despite the criticisms of retention, schools have not been required to hold back many third graders. In the years the guarantee has been in effect, promotional rates have ranged between 93 and 96 percent, even though third grade reading proficiency rates have been much lower (67 percent in 2018–19). These sky-high promotional rates are explained by allowances for alternative assessments, exemptions for certain students, and a low promotional bar. In 2018–19, for example, students had to achieve a score of 677 on the state third grade ELA exam to be promoted—barely above the basic level.[1]

A recent bill introduced by House lawmakers (HB 73) wouldn’t just weaken the retention requirement; it would scrap it altogether. In committee hearings, familiar objections to the policy have been raised. But one witness suggested, in a new twist, that the reading guarantee isn’t working as intended. His claims were based on a 2019 Ohio State University analysis of fourth grade NAEP reading scores, which while informative, offer a limited snapshot of achievement patterns in the years in which the reading guarantee has been in effect (the 2017 and 2019 rounds are arguably the only ones that apply). What wasn’t examined, however, were trends in third grade ELA state test scores. This was likely due to transitions in state exams that left only a year or two of consistent test scores at the time of that study. But we now have four consecutive years of data from the same state exam, so we can get a more complete picture of achievement trends under the reading guarantee law.

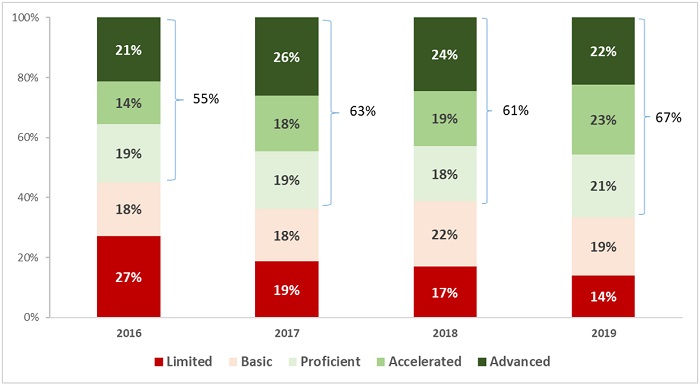

Lo and behold, we do see noticeable improvements in the state assessment data. Figure 1 displays the results for all Ohio third graders. We see an uptick in proficiency rates—from 55 percent in 2015–16 to 67 percent in 2018–19. Also noteworthy, given the guarantee’s focus on struggling readers, is the substantial decline in students scoring at the lowest achievement level. Twenty-seven percent of Ohio third graders performed at the limited level in 2015–16, while roughly half that percentage did so in 2018–19. Given the generally small and constant numbers of retained students over this period, it’s highly unlikely that the increases are due to students retaking third grade exams. The more probable explanation is that Ohio schools are improving their early literacy practices—perhaps even in response to the threat of retention—and children are reaping the benefits.

Figure 1: Results on Ohio’s third grade ELA exams, all students

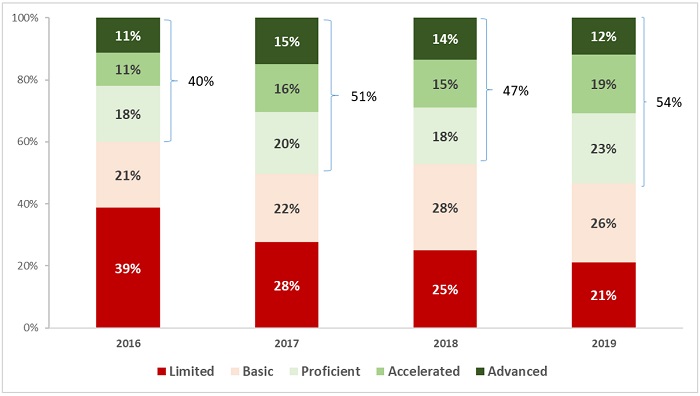

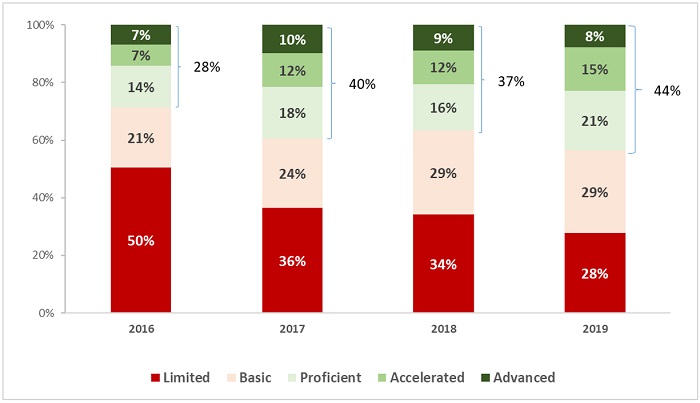

Source (figures 1-3): Ohio Department of Education, Advanced Reports

Figure 2 shows data for economically disadvantaged students. Although they generally score at lower levels than the statewide average—reflecting well-documented achievement gaps—we also see promising signs of improvement. In 2015–16, just 40 percent of economically disadvantaged students scored proficient or above on their third grade ELA exams; that number increased to 54 percent by 2018–19. We also see a substantial decrease in the percentage of these students who score at the limited level.

Figure 2: Results on Ohio’s third grade ELA exams, economically disadvantaged students

Figure 3 displays third grade ELA test data for Black students. We again observe marked improvements. Proficiency rates rose by 16 percentage points from 2015–16 to 2018–19, along with a large decline in the number of Black students scoring at the lowest level on the state test.

Figure 3: Results on Ohio’s third grade ELA exams, Black students

The progress seen in the charts above are not proof positive that the reading guarantee as a whole—or its retention provision specifically—is working. It may be other factors that are driving the improvements. Yet rising pupil achievement on state exams shouldn’t be ignored or brushed aside. Far fewer third grade students read at dangerously low levels, while increasing numbers reach the state’s proficiency bar.

To be sure, these data show that Ohio still has work to do to ensure all children exit third grade with solid literacy skills. Given the pandemic-related learning losses—likely worse in the early elementary grades—this imperative will become even more urgent in the months ahead. Weakening the reading guarantee isn’t the way to drive these much-needed improvements in early literacy. Rather, lawmakers would be smart to stay the course on policy reforms that seem to be working for Ohio students.