According to the state’s most recent annual report on educational attainment, 49.5 percent of Ohio adults had a postsecondary degree or other credential of value in 2019. That’s an increase of 14.8 percentage points since 2009, but it’s still a long way from the 65 percent goal state leaders set in 2016. To bridge the bulk of the gap, Ohio will need to focus on adult learners. But to maintain growth and strengthen talent pipelines, it’s also crucial to focus on future adults: current and rising high school students.

Ohio already has a decent foundation. Most high schoolers have access to a broad range of career and technical education (CTE) programs. State graduation requirements include a career-focused pathway. Dual credit opportunities are plentiful in both academic and technical fields. But even with these myriad options, thousands of Ohio students graduate each year with no industry-recognized credentials, no solid job prospects, and no idea how to make postsecondary education work for them. The pandemic has likely made things worse. It’s changed the economy and made in-demand credentials even more valuable for both employers and graduates, but information about and access to these credentials hasn’t necessarily improved.

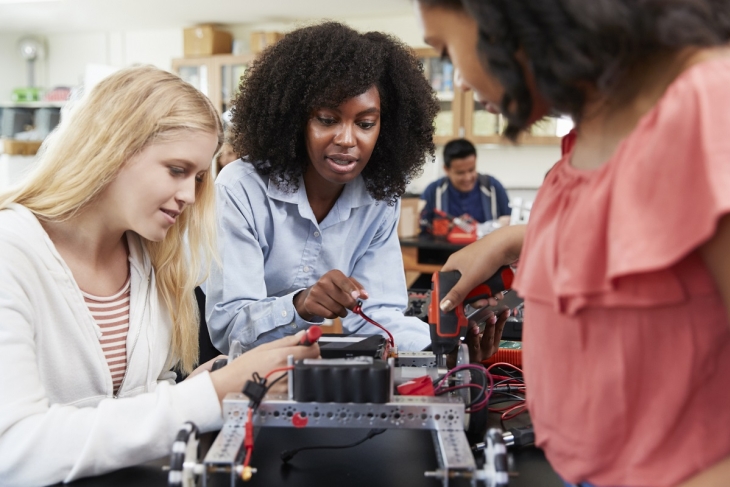

State leaders can help by investing in innovative high school models that prepare students for college and career. These schools give students a solid academic foundation but also provide career opportunities through internships, mentoring, and work-based learning. Students follow rigorous pathways that lead not just to a high school diploma, but to industry-recognized credentials and associate degrees in well-paying, in-demand fields.

Ohio already has a few schools like this. There are dozens of career centers across the state that offer students CTE programming in addition to traditional high school courses. Early college high schools, like Dayton Early College Academy or Metro Early College High School, require students to complete college coursework and internships to graduate. But these schools and programs serve only a fraction of the state’s high school population. To keep attainment numbers growing for the long term and to aid young adults in navigating a post-Covid world, Ohio needs to invest in other models, as well.

P-TECH is a promising option. Unlike a typical high school, P-TECH schools span grades 9–14. Students graduate with both a high school diploma and a two-year postsecondary degree, and they participate in work-based learning experiences, such as mentorships and internships as they work their way through school. In his most recent executive budget, Governor DeWine proposed a pilot program that would permit schools to apply for funding to implement the P-TECH model. Unfortunately, the pilot didn’t make it into the final approved budget. But lawmakers can and should revisit their decision. Ohio’s immensely popular College Credit Plus program makes the postsecondary aspect of the model relatively easy to implement, and programs like TechCred have proven that there are plenty of businesses invested in credential attainment.

If state leaders are interested in giving advocates and communities the freedom to create their own innovative models, a recent paper entitled The Big Blur offers some insight. It proposes a new educational model that, like P-TECH, would erase the dividing line between high school and college by creating new, cost-free institutions that serve sixteen- to twenty-year-old students. Foundational coursework from the final two years of high school would be combined with career-specific training. Work-based learning would be a key feature, and students would have clear, step-by-step guided pathways that lead to high school diplomas, as well as postsecondary credentials and associate degrees within specific fields.

Creating and running these new institutions would be a huge undertaking. Lawmakers would have to set clear legislative guardrails around incentives, governance, and staffing. But they would also need to offer meaningful flexibility and plenty of funding and technical support. There are a lot of potential hurdles. But there’s plenty of time before the next budget to sort through them and create a promising pilot program.

If lawmakers are serious about addressing attainment gaps, making room for innovative high schools is critical. There are plenty of ways to do so. State leaders could increase Ohio’s investment in schools that already exist, such as career centers and early college high schools. They could bring in proven models like P-TECH. Or they could create and fund pilot programs that make it possible for advocates to build completely new institutions. Regardless of what they choose, one thing is certain: It’s time for Ohio to get innovative with high schools.